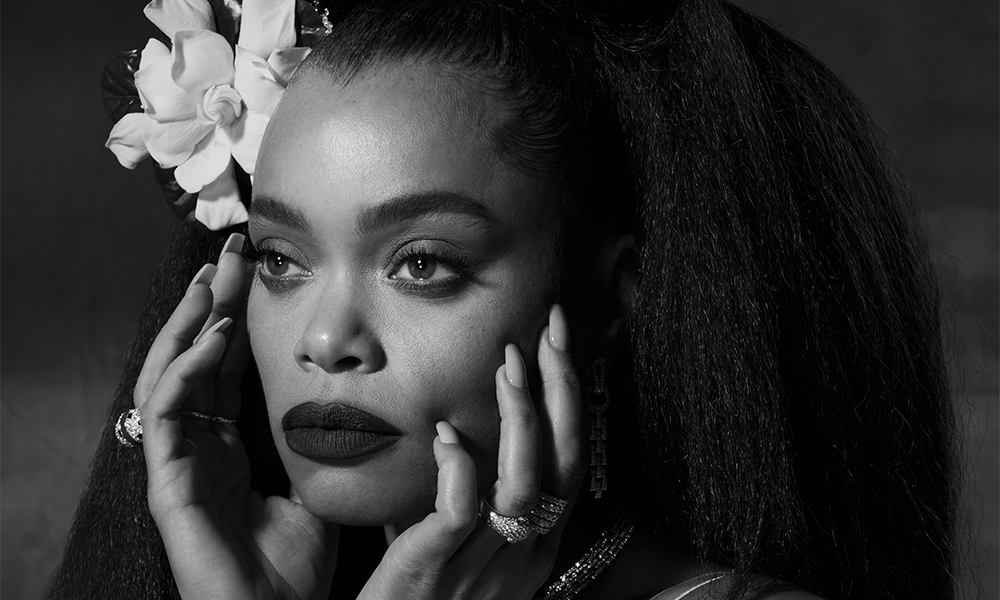

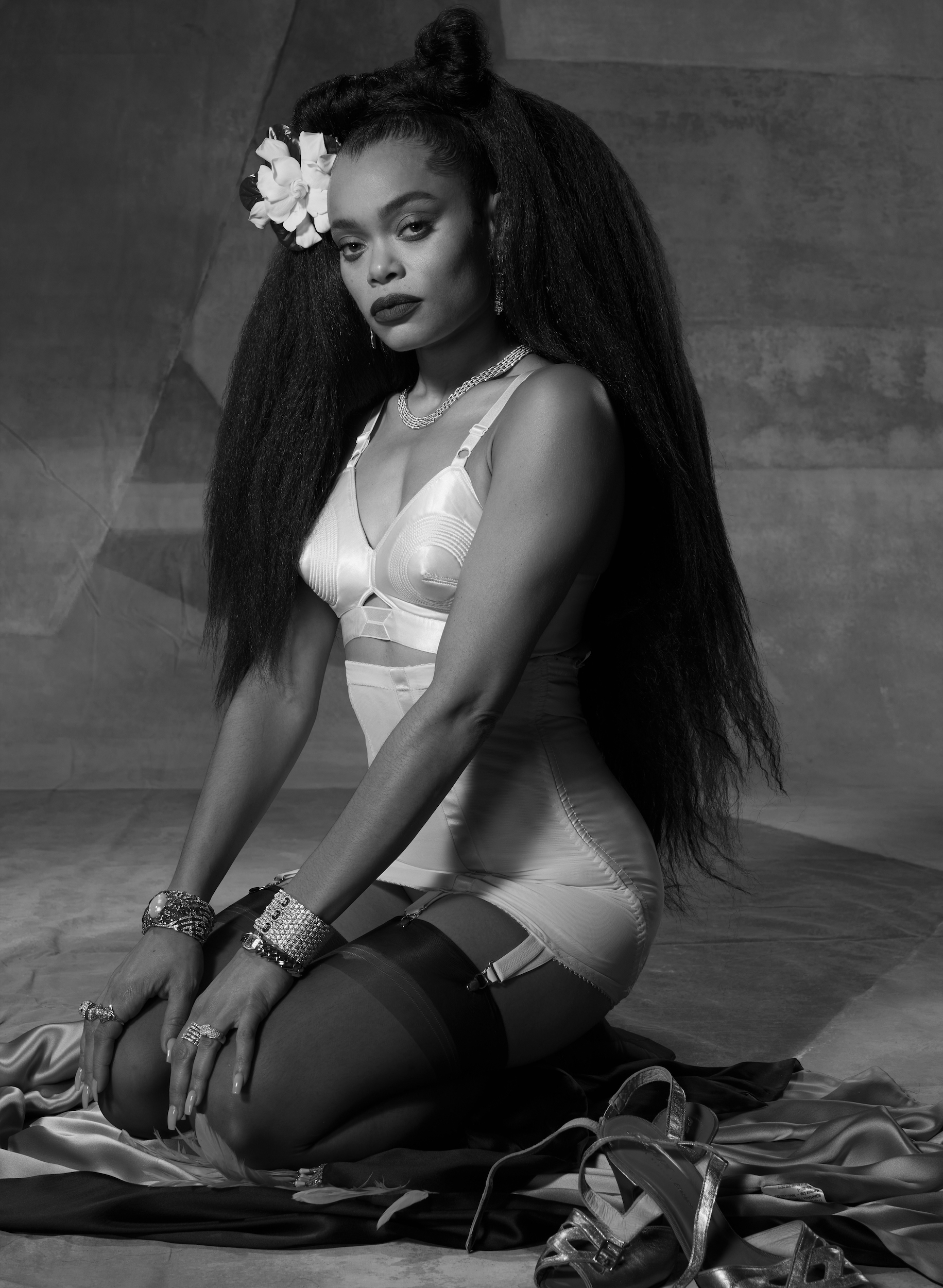

V128: Andra Day is Billie Holiday

As the lead in Lee Daniels’ new Billie Holiday biopic, actress Andra Day delivers a supernova performance, which brings the lady of blues’ many facets into dazzling focus in our V128 Cover Story.

This cover story appears in the V128 issue, now available for pre-order.

Billie Holiday’s life was so immense, so soaked in motley experiences, that it can be hard to grasp as a whole. In part, this is why the general populous knows only fragments of the Philadelphia-born jazz and blues singer’s story: She struggled so heavily with drugs that they eventually cost her her life, and that she was one of the few Black artists to “make it” in the ‘40s and ‘50s, when aggressively racist Jim Crow laws still governed much of the U.S. She suffered so deeply from heartbreak that she has become an international symbol of it.

With his latest film, this February’s The United States vs. Billie Holiday, Lee Daniels has set out to change that by lifting up the rug and casting a spotlight on what society has swept under it. It is a story of persecution, not so much by independent racist parties (the Klu Klux Klan, for example), but the U.S. government itself, which sought to persecute and jail Holiday for seating people of different races together in her audiences and singing Abel Meeropol’s song, “Strange Fruit.” With lyrics like, “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees,” the piece plainly evoked the horror of lynching, much to the outrage of the Americans who were still fighting for segregation. There are obvious connections to the brute police force against Black Americans that continue on to this day.

As Holiday, acting newcomer Andra Day is penetrative. Her performance pierces into you and leaves you unable to forget what you have felt and seen. That potency spans emotive stage performances (decked out in nine different Prada looks, with Paolo Nieddu as the costume designer for the film), or her drug use while off of it. Day metaphorically—and literally—strips herself naked, embodying such a lovable version of Holiday that you miss her once the film ends. You feel as if you are watching history brought to life. Yet there is also the sense that Day, with her phenomenal portrayal, is creating history of her own.

V spoke to Lee Daniels and Andra Day over the phone in late November for their first-ever joint interview, recounting a story of meeting one another that kicked off with immense doubt and ended in a life-altering experience.

Mathias Rosenzweig: Lee, why did you want to make this movie? And Andra, why did you want to be a part of it?

Lee Daniels: This is our first time doing [an interview], so you’re catching us fresh. I can tell you that I wanted to do the film because the movie that really made me want to direct was [1972’s] Lady Sings the Blues. It was the first film that I’d seen, as a 13-year-old kid, where there were two Black people that were beautiful and were in love. And I didn’t know anything about Billie Holiday at 13. I just saw a couple in love, and music, and beautiful fashion, and I could smell the food. I could smell the fried chicken jumping off the screen. And I said, “Oh my God, I want to do this. I want to make people feel the way I feel right now.”

So that movie intoxicated me, not only with the feeling of loving my people, but a feeling of understanding that I wanted to continue to tell stories. I wanted to do what that film did, which is tell beautiful stories about love. And so that started the whole Billie Holiday thing. And when I found that that [depiction] wasn’t really the case, I really wanted to know what happened. And I think that the civil rights of it all blew my mind, and her story blew my mind. So that’s the reason why I wanted to do it. Andra, why did you want to do it?

Andra Day: Like you said, the civil rights. The truth of it all actually mattered to me. Because, as Lee knows, and we’ve laughed about this a bunch of times—at first I was terrified. I was hesitant, and I was like, “I don’t know if this is a good idea.” Also, I loved Lady Sings the Blues. I love Diana [Ross’] performance. So it was actually part of the reason I did not want to do this. She killed the role. It’s beautiful what she did. But Lee, I remember we sat down and had dinner at Soho House, and the first thing I really liked was actually your energy. We bonded over good stuff and bonded over the bad. It was your character and your need for authenticity that I really enjoyed.

LD: I mean, I drove to Soho House not really wanting this to happen.

AD: You told me [laughs]!

LD: My managers, people who work with me, they were like, “[Andra] is who you have to hire.” And I was like, “Fuck y’all.” I was like, “Poor girl, she doesn’t stand a chance.” But then we met and when I first looked at her, I saw her spirit. I got chills. She wasn’t a desperate actress that just wanted to do it. I could tell she was questioning whether she was good enough. To me, that is when you know that you are really dealing with a perfectionist. She wanted to do the role justice. That’s all you’re looking for as a director.

MR: Despite Billie Holiday being long gone, her music and legacy remain such a big part of so many people’s lives. Can you talk about the pressure of portraying her?

LD: I did not want [her] to be a victim. To the point where we had several issues after, and I realized that she was a little too hard. And one of the things I never wanted her to do was cry. I wanted her to play tough, but she was a little too tough. We had to do some reshoots. So I wanted to show that she wasn’t a victim. And then I wanted to show…hmm, how do I say this right? How do we fall in love with someone who is a drug addict, someone who will kick your ass? It was like walking a tightrope for me because I tried to make sure that I did her justice, but that we also showed her flaws and made her beautiful. That was really, really, really scary. We were both scared.

AD: You just asked the question where you were saying, “How do we make her lovable?” The reality is, you did it by telling the truth, by not sugarcoating. Because really, she was adored. It’s like, if you tell the truth about Billie Holiday, people are going to fall in love. She was one of the only artists who had the power to captivate audiences of all races around the world. She was a global superstar. People would write about her in the paper, and they would write positive things and they would write negative things. But ultimately, everybody really, really loved her. You know, I really love this woman so much. And I always have. She’s charming. She makes me laugh. We have conversations. I know that sounds crazy. She’s nuts. And she’s hilarious. You want to be around her presence all the time.

LD: Just when you think you know her, you don’t. We wanted to show how spiritual Billie was. So you see her in church, and then the very next shot you see, it’s with her legs wide open and backstage at Carnegie Hall, smoking a cigarette.

AD: Oh that one made it in there? The one in the dressing room?

LD: Yeah. Wide open.

MR: Andra, you haven’t seen the movie yet? I think you’re going to blow yourself away when you see it.

AD: I know, it’s so funny. You know, my memories from [filming] are still so potent. And it’s like, I don’t want to do anything to alter that. And I’m telling you—when I say this, I’m not exaggerating, I’m not saying this because we’re on the phone. But [filming this] was one of the greatest moments of my life. It was really a paradigm shift.

LD: I agree. It’s magic.

AD: And that’s why I haven’t seen it. Ultimately, I feel like I’ll do it in a premiere situation. And I want to say, about being on set, there was also this urgency. It wasn’t like we were doing a casual comedy. There was urgency on set every day, day in and day out.

LD: This was really a call to arms, because we all knew, we could all feel it in the air, that Black men were being killed. We knew what was going on in America. And this was right before Breonna [Taylor]. You could feel the hatred in the air and it was important. We needed to capture this right away.

MR: Lee, you mentioned not wanting to portray Billie as a victim. But she certainly was a victim of certain things. Can you elaborate a bit on that?

AD: My experience with Lee, with loving [Bille] and knowing her in the movie, is that he did not want her to have a victim mentality. She was a victim of experiencing trauma. She was Black, at that time in this country, period, but she was not a victim in the mind. [Crunching sound] and I just want to say, I’m eating my Doritos right now while doing this interview.

MR: You just do whatever makes you happy [laughs]. Obviously, you are a singer and you played a singer. What was that like for you?

AD: There are ways that we’re similar, but there were things like the drugs that I needed to get an understanding of—the addiction. I’ve had many conversations with people about it. I read her biography. I read everything I could get my hands on. And I understood the need to say something with a platform. What I needed was to grab the sense of urgency, that if I sang “Rise Up,” I could be killed by the cops. You could be doing nothing, sitting in your house, and get shot by the cops. And then again, the deal with addiction. [Speaking for Holiday:] “Why am I an addict? Why do I do drugs? Why am I such a heavy drinker?” So I really needed to understand that trauma and that pain. You have your emotional pain, right? I’m sure you have your own traumas in life. Imagine a drug that’s tied to all of your emotional pain, that’s tied to your memory, that’s tied to the way you function…it can actually remove your emotional pain. And then when you’re coming down from that, and you want another hit, and you’re not even getting high. I sat with a former addict who taught me about that stuff. It was really intense. I have different ways that I process my trauma, but I really needed to understand why she chose to process her pain in this way. [To someone in the same room] You are taking pictures of me eating fucking cheese Doritos. You are an asshole. [Everyone laughs].

MR: What do you guys hope the impact of this movie will be?

AD: I hope this is a revelation. First of all, telling Black women’s stories is huge for me. I would have people tell me, “You’re never going to do a role like this. There aren’t many roles for Black women.” And I’ve said this multiple times, but to me, that statement is baffling. I don’t understand. One of the biggest things is I wanted people to get to know her. We have to understand that a lot of [Black people’s] stories have been intentionally kept from people, and that the history we hear is not accurate. You cannot tell American history or world history without telling African history. You have to understand how much of our history has been wiped off the map because that was their goal. With Billie, the narrative basically eradicated her, or tried to, but they couldn’t because she was too famous. So they told the story but they spun it in a different way. I want this to tell the truth of our narrative. I want it to be a revelation like, “Okay, apparently I’ve been lied to about a lot of these stories.” Like with [the film] Hidden Figures, that three Black women were responsible for sending us to space and programming the first computer. What that would have done for me as a little girl to have known that…

LD: When people walk away from this film, I want them to feel the way I felt making it. I looked at the way she stood up to the government, and it just made me think, “[I want to] get people to grow, to not be afraid of the system.” The system is flawed. It was never meant for Black people, for us. I think [Billie] understood that and was able to speak about it. She was like, “No, I’m not the one. I’m not the two and I’m not the three.” Also, it was a Black set. Black cast, Black director, Black team. I keep forgetting what I bring to it. And I’m not bragging about it. It’s the sense of a cookout. It’s just what I bring to the table as a director…there needs to be more Black films, and there needs to be more Black directors.

AD: Everybody [on set] was so supportive and concerned with each other. The integrity was there; the collaboration, the creativity. It just destroyed this whole idea that there’s only limited space for us.

Check out ‘The United States vs. Billie Holiday’ Official Trailer and full feature premiering February 26, exclusively on Hulu.

Discover More