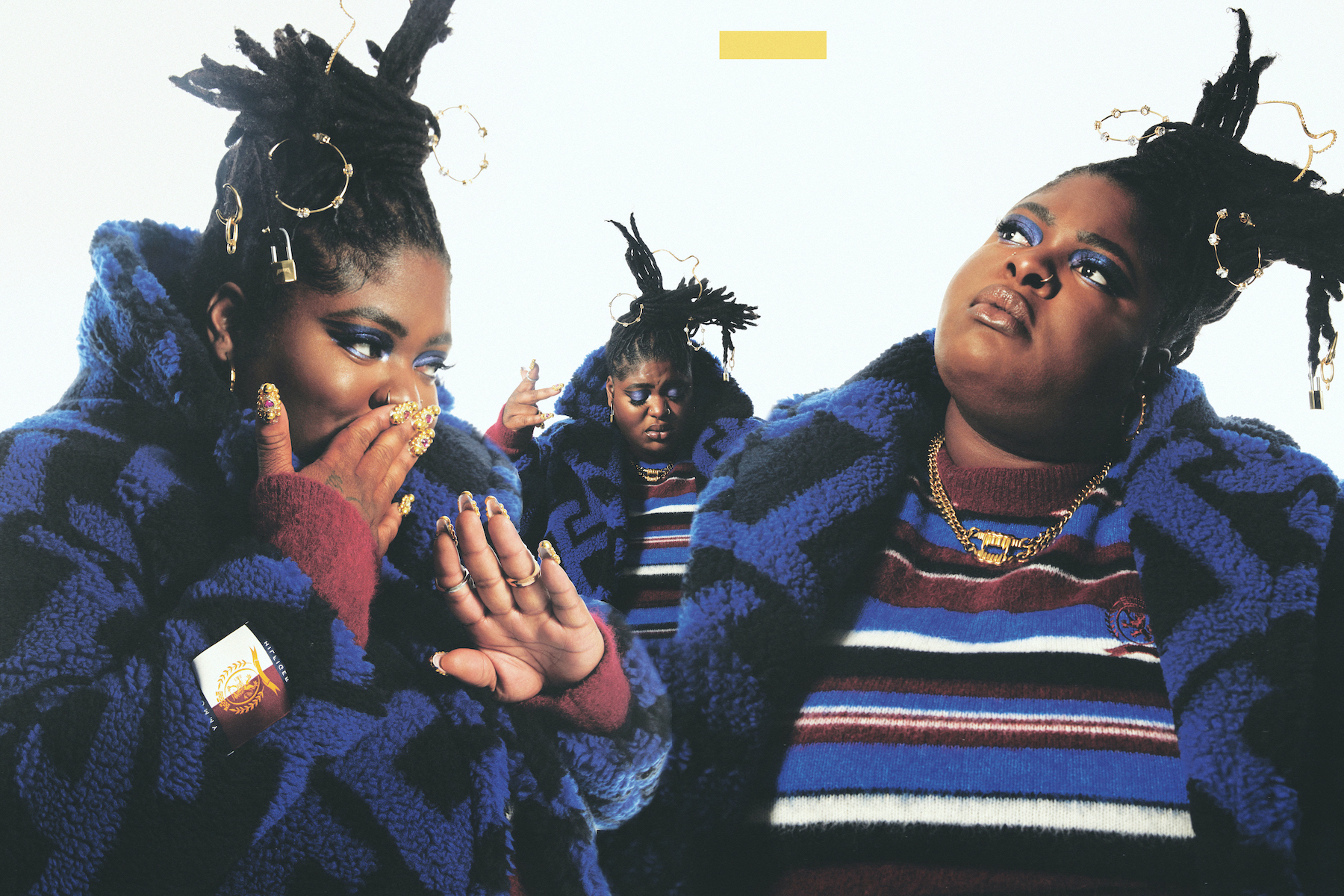

Caught Up In The Rapture: Chika

In conversation with Grammy-nominated MC Rapsody, the rapidly rising artist Chika discusses the healing power of music, finding inner purpose, and the evolution of Hip Hop

Since bursting onto the scene just three years ago, Alabama-born artist Chika has captivated audiences with a sincere lyricism and sound that blends elements of Hip Hop, R&B, and Soul. Now, the 2020 Grammy Nominee for Best New Artist connects with critically acclaimed rapper, Rapsody, over their shared passion for music and sincere connection. Below, the kindred spirits discuss the realities of mental health, breaking into the genre, the importance of supporting women in a historically male-dominated industry, and so much more.

Read the exclusive interview below.

RAPSODY: I wanted to start with asking you: what made you pursue rap? What made you fall in love with the genre and who were some of your early inspirations? I’m just interested to know your journey.

CHIKA: Oh, my journey is so weird. It doesn’t make sense to me. It’s funny though because my parents are Nigerian, we didn’t grow up with the same influences as most Hip Hop artists. We grew up listening to Afrobeats and Reggae. I didn’t have the formative youth experience with Hip Hop besides being from the South. I’m from Alabama, we listened to OutKast and Tip (T.I.), certain things like that because I’m Black and I’m from the South. So I didn’t know that Hip Hop was so deeply ingrained into what I love.

I just knew that I love to write, sing, and play guitar. And when you do poetry and music, it ends up being rap. And while falling in love with artists like Wale and J. Cole, probably towards the beginning of high school, I was secretly writing raps and nobody knew—because back then to be a rapper, you had to be good at it. I didn’t believe in myself yet, so I was just quiet. And eventually I branched out from that and someone was like, ‘Yeah, you’re good.’ And I was like, ‘Thanks.’ And I just kept doing it. But I want to know about your background with Hip Hop.

R: Man, I really think that’s dope and interesting. Because I’m from North Carolina, so I align and connect with you—I understood how much I loved Hip Hop and I wanted to be a part of the culture and the way of being an artist. I wasn’t exposed enough to the point where I saw it as something I could actually do. I grew up a Jehovah’s Witness, and in the house, my parents listened to a whole lot of Soul, which is probably why most of my music is so Soul-based—because that’s all that was playing in the house. Luther Vandross, Tina Turner. I remember growing up, Hip Hop albums had the “explicit” sticker on it. My mom was like, “Nah, we are not getting that.” And I remember in fourth grade I had this tape that somebody gave me and I was in my room listening to it and the tape was like a “A tisket, a tasket, a condom in a basket.” My mom was going to bust down the door into my room!

C: Oh no.

R: It was bad.

C: A condom in a basket is nuts. I feel that, because we grew up Southern Christian. It was like, “No, we’re not playing that in this house.”

R: But at the same time, my mom tried to be a parent, like, “Yo, I gotta watch what you listening to.” But my mom is the youngest of 13 and my dad was non-denominational, so we did have a little leeway. And they both worked all the time, so I was gonna listen to what I was gonna listen to. But if you grew up in LA or New York, you got to go outside and see Biggie, Mos Def, MC Lyte, or in LA, you got to see Tupac shoot a video. Everything I saw was on TV. So I started writing poetry first and I wanted to rap, but I didn’t necessarily believe I could do it. I didn’t even understand, like, where’s the studio? I’ve never been in a studio at the time, I’ve never been to see somebody perform live.

C: We’re so similar.

R: Very similar in that way and I feel like I bloomed late. I was 23 when I started, I went to college in a bit of a bigger city, so you get exposed to more. And I just fell into Hip Hop that way. But it was definitely organic.

C: Organic, that’s what I love about you.

Earrings (worn in hair) Swarovski, Rare Romance, Lady Grey

R: Absolutely. I don’t know if you’ve experienced this, but I even remember earlier on when I was starting, getting comments like, “Yo you’re from a small town in North Carolina, your music can’t be interesting because you didn’t grow up in the city and you didn’t have a hard life. So what do you have to talk about?”

C: That’s so funny. My first ever recorded rap song is called “Can’t Talk About It.” It was literally about the fact that I don’t have the street background like a lot of people [in Hip Hop] and I don’t think it requires that. I think there’s a beginning of Hip Hop and there’s an evolution of Hip Hop, and it’s turned into this massive, cultural phenomenon that is not only a way for us as Black people to express ourselves—via the way that we culturally do—but also it’s become a way for poets like us and people who really attach to the words of music and wanna communicate through that. That’s what Hip Hop has become. And it’s this beautiful thing. So it’s funny to see how the culture has shifted because there’s so many people now who don’t have the “traditional” background of what a Hip Hop artist used to look like. And it’s cool to see what we’ve become as a community.

R: I feel like we’ve always been that, right? Hip Hop was always a space for everybody to express themselves in different ways. Whether you had a harder upbringing or you’re talking about love, your mama cooking greens, or your homies at the back of the bus jawning on each other. But since it’s become commercialized and fed a certain narrative, people think the only thing that could be entertaining is the hardships, people think you gotta be in the hood and you gotta go through this struggle. And Hip Hop is not that, Hip Hop is everything. It exists in all spaces, all places. And that’s the beauty of it, celebrating our individuality and authenticity of who we are and just telling our stories. And those stories matter. And now with the Internet, it allows us even more freedom to get those stories out.

C: Yes, I think Hip Hop at one point was probably just a conduit for White America to understand what it was like to be Black in America—not even really understand, but just have a voyeuristic view of what it was to be Black in America at a certain point. And so it became this thing where it was like, “Oh, not only is the music good, but we’re hearing these stories.” And as time goes on, cultures evolve and shift and our realities change—five years ago is nothing like it is today. So if we were to stick to what Hip Hop always was and started as, it wouldn’t have evolved into this space for people who don’t have those stories to be able to share. And Black people are not monolithic, we have so many different ways of life and experiences, so it’s really dope that Hip Hop has now created less of a commodification of Black trauma and more of a space for Black people to feel like they can be heard.

R: Absolutely. Let me pick your brain on this because I agree with you a hundred percent. Do you still feel like on a mainstream level, that [sentiment] is celebrated in that way? Do you feel like there’s still enough diversity [in the industry] in terms of men and women?

C: Oh, let’s get into it!

R: Yeah, come on. That’s what we are here for.

C: We ’bout to be messy.

R: Both of us tell whatever stories are true to us. But at the same time, when it comes to a mainstream level, it’s one strong narrative in both cases—with women it is hypersexuality. Where if you’re an up-and-coming female and you don’t have a strong circle around you, you would think “The only way I can make it is if I go ‘sex.’”

C: I think it’s a symbiotic relationship between the women in Hip Hop and the actual economy of Hip Hop. Because the market is going to push whatever the consumer is drawn to. And once the market begins to push it, it’s all the consumer gets. And so it becomes this vicious cycle where it’s not necessarily about whether or not you’re talented—and lucky for us, we’ve been able to be celebrated for what we can do and not just how we look and what we talk about, even if it is hypersexuality. But at this point, the market of Hip Hop has taught women that in order to survive in that ecosystem, they have to present a certain way. And Hip Hop is not in its infancy, but it’s young. It’s an adolescent phase where we’re allowing ourselves to grow past that. And because we are not necessarily the gatekeepers of what it is to be in the music industry, the market is gonna dictate what people hear and what people hear is what they’re gonna emulate.

Because for me, the artists I listen to absolutely shaped what I do now. I mentioned earlier, Wale, he’s like my big brother, but before that I was a huge fan. And the way that I write directly lines up with how his music used to sound and the way that we speak to each other even. So I can only imagine that young ladies who are influenced by women in Hip Hop right now, their shit is gonna sound like them. And so until the market shifts to reflect that there are different types of women and men in Hip Hop, it’s gonna be more of the same.

R: That’s a great point. I have another perspective, but you completely hit it on the head.

C: What’s your perspective?

R: I’m gonna add to yours, but you made me think of something. For me, it’s come to a point where people can’t even think on their own anymore to even say what’s dope or not. I was with my sister one time and she was watching one of the reality shows and she was like, “Man, I don’t love this show.” So I was like “Why are you watching it?” She was like, “Because that’s all that’s on.” I was like, “If you don’t like it, you should probably turn it off because if you continue to watch it, they’re going to assume that the ratings are up because you’re watching it.” You have to fight against the system to get something else because if you support it, that’s what it is. And it just made me think of Lil’ Kim, she was ill when she came out, I love Kim. And she was so successful because it was just authentic, raw, new and in our face in that way. And it looks like the market was like, “Oh, this is making big bucks. This is what we’re gonna continue to push.” But that’s all that they got behind and we never really got back from that.

And my other perspective was that I like some of it too. Some of it I don’t, some of it I love, it’s just about authenticity and if you’re dope or not. But then I’ll be online and you’ll see people just sharing, saying “Yo, you should check this person out or that person. It’s something different.” And most people are like, “Ah, that’s boring. It ain’t sexy, it’s not gonna sell.” I’m listening to that and I’m just like, “Man, is that what it’s come to where that’s all we expect of ourselves?” Like what life are you living where this is all you listen to 24/7. You don’t go through any other emotions that music speaks to?

C: I feel like that would be such a boring existence for me as somebody who lives my life through the lens of music. That would be incredibly boring, I listen to so many different things that I feel like my experience can be encompassed by my playlist. But humans are such social creatures that we wanna be at the heart of it, to be able to relate to each other. And so the majority of the world is only listening to one type of music, and you’re listening to another. There’s people who are like, “Yeah, I love the underground scene.” But for the most part, everyone wants to listen to shit that they can talk about with everyone. And so when the market is pushing this one type of music or this one stereotypical image of what a Black woman is, there’s gonna be people who are like, “Oh, there’s other dope people that you should listen to.” But for the most part, they’re gonna be ostracized from conversation because they don’t have a relatable artist to talk about.

It’s funny because for me, when I was first coming up, I used to screenshot every single time somebody was like, “Yeah, she’s dope, but she’s not gonna make it because she’s not marketable.” And it made me laugh because I would hear people in that same breath saying, “You’re an amazing artist, however, you will not get the opportunities because nobody will push you.” And it’s wild to see consumers say stuff like that because they are supposed to be the ones dictating the market, not the other way around. And so we’re in a spooky season when it comes to Black music and Hip Hop and what it means to be fully represented. It’s a little bleak out here.

R: And that was my whole thought of why it’s so disappointing because people are sheep, in that same breath, they’re like, “Yo, you’re amazing, but you won’t make it.” And that’s a very sheep mentality to think that you like something and you won’t even support it.

C: Yeah, it’s weird.

R: You know what I’m saying? It’s a complete contradiction.

C: It literally is. It’s like, how do you not see that? I knew that my talent would take me where it needed to. And it has, thank God. But the funniest part about it is seeing the tides turn and shift in my favor because I was never going to let these sheep minded people tell me what my future looked like. And I kept doing it and I got better at it. It became a hive mentality, once one person was like, “Yo, she’s dope,” another person would be like, “Oh, you think so?” And then over time it became this thing where I have a solid fan base now because of the people who are willing to check shit out. And now there’s enough of us that liking my music is no longer a debate or “is she marketable?” It’s just you like what you like and that’s what it’s supposed to be.

R: Exactly, let me ask you this, how do you deal with it? Because we’re all human at the end of the day and we have human experiences. Was there a moment where music clicked for you? Because I’ve had days where it’s just like, “Man, can I continue to do this? Do I want to do this?” But what was the one moment of, “Okay, I know my reason, I know my purpose. This is why I want to do it, regardless of what’s in front of me.”

C: I’m someone who’s really vocal about mental health and all things Chika. And so last year I had a mental health crisis of sorts where I ended up getting 51/50ed, which is basically an involuntary hold to make sure that you’re not a danger to yourself or others. So I was at this facility in California and I remember what led to that moment was feeling completely overwhelmed, under-appreciated, and overworked. And it was in the middle of COVID and so I was just like “I can’t do this.” And right before that, I had tweeted “I’m retiring, I’m out, I can’t do it.” And so when I ended up in there, it’s a 72 hour hold, I remember being there for a couple days and I was like, “Yeah, I’m ready to go home.” But I was around so many different types of people who have so many different backgrounds and stories. And so this one kid came in and he was really really out of it. He wasn’t talking to anybody, he looked terrified and scared like he didn’t know where he was. And I remember being like, “Alright, well when I first got here, I was not wanting to be here. Lemme go try to talk to him.”

So I did and I eventually learned that he was a paranoid schizophrenic. And so the first day of him being there, he said “I don’t know what I did, I killed somebody.” And I’m like, “What are you talking about?” And he’s like “No, all of my favorite artists, they keep dying.” And he listed Xxxtentacion, Juice WRLD, and Mac Miller. And that’s when I began to realize—he thinks that he is the cause of these people passing away. And so I’m trying to reason with him, saying like, “Hey, friend, no that’s not what’s going on. They have millions of fans, you’re not the reason for this. This is not your fault.”

And he was completely dissociated, but he looked at me and was like, “You mentioned doing music.” And I said, “Yeah.” And he was like, “Could you rap something for me?” And I was really taken aback at the request because he’s in the middle of a full breakdown. And a month before, I had put out my second EP, so I just ended up rapping the song “Save You.” It was the most incredible thing to witness because the light came back to his eyes. I’m getting chills talking about it.

I remember seeing a visible shift in him where music reminded him of who he is. He understood once again that music is what he loves. For a brief moment, it was like his schizophrenia went away. It was nuts to see. And afterwards he was like, “Thank you, thank you,” and he was back to normal and I had never seen him normal—he got there in a catatonic state. So this was my first time actually meeting him, after our rap. And he started talking about why he loves music and why feels so captivated by what art does for him.

And in that moment, I ended up leaving a couple hours later, but on the way home I was thinking to myself—I really was trying to quit music, I really was trying to get outta here. Not just quit the industry, I was trying to quit life. I was trying to go. But I was able to connect with a stranger on a super deep level, have a meaningful conversation, and help him remember who he is based on spitting something that took me 30 minutes to write. I think of that moment any time I just want to give up because I’ve never seen anything like that. And I think it’s less about me and my gift and more about what music means on a larger scale and the fact that I’m not just doing this for me. Yeah, I have dreams, yeah, I wanna be appreciated, yeah, I wanna make sure that I leave my mark. But at the end of the day, I didn’t start doing music for that. So I’m not gonna end it for that.

R: That’s beautiful, man. When you get to find your “why” again, right?

C: Definitely. What was your moment?

R: Man, it’s so hard to follow that up. There’s several small moments, but one that always sticks out in my head—I was in South Africa and this four-year-old little girl and her mom came up to me and the mom said, “Tell Rapsody what you wanted to tell her.” And the girl was like, “I wanna be like you when I grow up.” And it’s as simple and small as that moment was—to travel across the ocean on a flight, 16 hours away to a whole other continent. People ask us all the time, “What do you want your legacy to be?” And at the end of the day, I just wanna inspire people through art. I wanna be a light for them to see the beauty in themselves. We appreciate to be seen, given flowers, these accolades, but at the end of the day, it’s the people and it’s about connecting with people. And that’s why your story is so powerful because that’s what we are all meant to experience in different ways with different people.

C: I love that, I really do. I’ve always said that I wanted to change how people process emotion and until they see someone that they can relate to, reflected in their media, that won’t happen. And so we do each other a disservice by only platforming and giving a voice to those who’ve already been represented. Not that they should stop being represented, but we need to broaden that space so that the next Rapsody will be able to see herself or the next Chika. We need to have spaces where the music is able to exist as it is and still inspire the people who it’s meant to touch.

R: Absolutely. And just thinking about the pandemic, if you didn’t go through something that was

C: Traumatic?

R: Yes, traumatic. I was moving, touring, I’m sure you were moving too. And everything comes to a stop. And you have to sit with yourself. You can’t party it away or mask it up in a good night or a studio session, whatever your thing is. You gotta really sit with yourself.

C: Oh, it was brutal over here.

R: Yeah, I felt that in your story and I felt my own heaviness. I was depressed through a lot of it. But just going through that growth and change—there was a lot of peeling back childhood trauma. That unblocked childhood that you gotta figure out: why do I really feel these emotions? What’s really going on?

C: I was doing shadow work.

R: Yes, shadow work, exactly. And you get to see yourself, but at the end of the day, we all go through this, we are all human. And that’s been a lot of the focus of my music. And people ask me all the time, like, “When’s the album coming out?” I had to remind myself to not be afraid to be vulnerable in that way. There’s so much coming at us and you find yourself like, “I know I don’t need to be afraid, but now I’m overthinking it because what do people wanna hear?” And it’s really like, “Fuck what they want to hear. This is where I am.”

C: Exactly.

R: I have to tell my story. You can like it, love it, whatever [but] I’m onto the next while you’re trying to figure that out. The courage of allowing yourself to be that way, in the same way you allowed yourself to open up, there are a million people that are dealing with stuff that they don’t even talk about. And it’s the music that’s gonna heal them at the end of the day. So that’s the best that we can do, be true and authentic to who we are.

C: The months leading up to COVID, I was doing press and I hadn’t even fully begun my foray into what my career was gonna be. So I spent months with my manager, they’re like, “We’ll get this press out of the way, and then in March,” hint, foreshadowing. “And in March when you drop your EP, everything’s gonna change for you. It’s gonna be lit.” And I’m like, “Alright, cool. I’m gonna get the hard work out of the way and then I’m gonna be able to meet my fans finally.” And three days after I dropped my EP, the world shut down. And so you gotta imagine what it’s like to just turn 23 and thinking that my life was gonna be so much different and now we’re locked in the house for two years.

Even with my Grammy nomination, I went to the Grammy’s in a year where you had to sit six feet away from every table. And then once your category was announced you had to go, there was no show. And so I had to sit and mourn what a lot of my dreams looked like in order to be grateful for what they actually were. And it was a really humbling and traumatic moment to be like, “I have no control over any of this.” And it doesn’t matter how much work I put into it, something could completely shift the course of what the world is doing and take away what you thought was your dream.

And so I had to spend that time hoping that things would change. I spent the first few months being like, “Is this gonna pass?” and then realizing that there were a lot of things I wasn’t gonna be able to do. And then wanting to be grateful for all of the blessings I had, but also realizing it’s still on the Internet, I’m still doing this from my house. Everyone looks at me like I’m this young, thriving rich kid. And it’s like, “Yo, I still am in my two bed, two bath, trying to make sure that my music is heard.” And if this is my peak, I didn’t even get to go on the road with it.

There was a lot of coming to terms with what you look at as, not personal shortcomings, but what life is and its unpredictability. And so the only thing that really does stand at the end of the day is the connection that we have to the music. My first EP was talking about me being out here and not knowing what the industry was gonna hold for me. My second EP was very much so like, “Let’s pretend that we’re not here. It’s a fairy tale, let’s write a different story.” And I just finished my debut album and it’s talking about everything—from the first EP to now. And I’m a different human than I was when I first debuted as an artist. And people need to be able to see that reflected in the music.

R: Absolutely. We’re ready for it, you know.? That’s what our life is. I’m happy to hear that there’s evolution there. You sound happy. I gotta ask, how are you today?

C: I’m feeling good. I’m in a much better space. I think the one upside to the pandemic was having to spend a criminal amount of time with myself and only myself in order to eliminate some of the things I didn’t know or problems for me. And being an artist, our entire career is to thrive off of validation because validation is what drives sales and it’s what makes you have opportunities. It’s constantly seeking the validation of the public. And so for me as a person who doesn’t need to do that in my regular life, it’s very ironic that my career path is one that requires me to look at everything, the way that I’m received, and constantly pick at myself. But with the time taken away from being out and in the public eye and doing the most, I have been able to really understand myself more and what I need. I feel like a more well-rounded individual. And in some ways I do think I’m grateful for COVID because had I not had to stop, oh my God, I don’t know who I would be. I really don’t, and that scares me. How are you doing these days?

R: Hey, I’m human, I have my days. I’m human, life be lifin’.

C: Life really do be lifin’, I need it to relax.

R: I wanted to tell you two things based on what you just said. I don’t feel like, for you and the artist that you are, that your validation comes in the same way that everybody else’s does. Because of your connection with people and the music, that is all the validation you need—your self-validation and knowing who you are in the story. You’re gonna be around forever as long as you do that. That was something I used to struggle with a lot in my career. Like, “Oh, I need to be at this award show, performing here. Why don’t I have what they have?”

But at the end of the day, I understood that because I have a connection with people and memories, that’s all I need. I’m gonna be able to do what I love forever. As long as I continue to keep that, it may look different from other people how my success is, but at the end of the day I’m at peace and I can look in the mirror. And I feel the same way for you. And I remember I called you in 2019 and I got off the phone and something told me, “Chika sounded different today when I talked to her.” And I wanted to tell you that even talking to you now, I want to make sure that I show up and be part of your village more. Because when I came up in this game, as far as women that did what I do, I didn’t feel like I really had a lot of women or sisters that I could reach out to for support. I had a village of guys but connecting with my girlfriends and my homegirls was different.

C: I really appreciate that because I think that is the toughest thing about what we do—the inherent competition-like aspect of women in Hip Hop. Because only in recent years have we been able to make the splash that we have, especially all at the same time. So it doesn’t always feel like you have anyone to reach out to, or if you do, it doesn’t necessarily feel like you’re gonna get real listening, wisdom, and being able to feed into each other because everybody’s trying to be so top secret about what their secret thing is, their power is. And I feel like my power is sharing, vulnerability, and openness. And that’s what feeds my soul. So you and I are on the same page with that. You know you got me, I’m over here. I may be chaotic, but I’m a good friend.

R: You’re an amazing friend and person.

C: Thank you so much. You’re never gonna have a boring day with me.

R: Let me tell you, you crack me up. Somebody sent me something the other day that you tweeted, I was weak. If nobody is gonna say it, Chika is gonna say it.

C: Oh, absolutely. Because I don’t care about none of this shit.

R: And you shouldn’t. And because you’re so creative and you have so much personality, do you see yourself doing things outside of music? I could see you writing a movie or something, you know what I’m saying?

C: Thank you so much. You’re really sweet, it’s gonna go straight to my head and my head is big enough. I’m a theater kid, my whole existence is being annoying at its very core. So that’s what it comes out as, I’ve always been a little bit too talkative and too unfiltered. And so I think my favorite thing to do is making music. But at the core of what I love is communication and any way that I can tell a story or paint a picture, that’s what I’m gonna do. So of course, I’m gonna be an EGOT. On television screens, making sure nobody forgets my annoying voice. It’s gonna be so fun. And I love that I’m just getting here and people are already like, “Oh no, she gonna be a problem.”

Below, stream Caught Up in the Rapture—Volume 1, Part 4—curated by Chika and Rapsody.

Discover More