Celebrating Prince’s Birthday With V84

V would like to wish Prince a happy birthday by looking back at an interview and photo series with the multi-talented and enigmatic icon.

In 2013, Prince was photographed by Inez & Vinoodh for the cover of V84. Three years later, the influential and supremely talented musician died at his home, which he had notoriously crowned Paisley Park, located just outside his native city of Minneapolis, Minnesota. As his hometown is currently the epicenter of the Black Lives Matter protests, it’s hard to imagine Prince staying quiet about the fight against racism if he still graced the earth today. “At important junctures in his life and career, Prince made conscious and strategic choices in his representation of race that reflected issues and dilemmas of both historical and contemporary relevance in the lives of many African-Americans,” wrote Twila L.Perry in an article titled “Prince, Music, Black Lives, and Race Scholarship“.

Prince’s roles as a singer-songwriter, musician, record producer, dancer, actor, and filmmaker destroyed the boundaries set upon people of color in the entertainment industry and left a mark on culture forever. His legacy unarguably lives on, like he told USA Today in 1996, “Not to sound cosmic, but I’ve made plans for the next 3,000 years.”

While we take today, what would have been Prince’s 61st birthday, to remember the cultural and musical icon, head below for the interview and photo shoot Prince did for V84. You can purchase this collector’s club issue here, and 100% of the purchase will be donated to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Everlasting Now

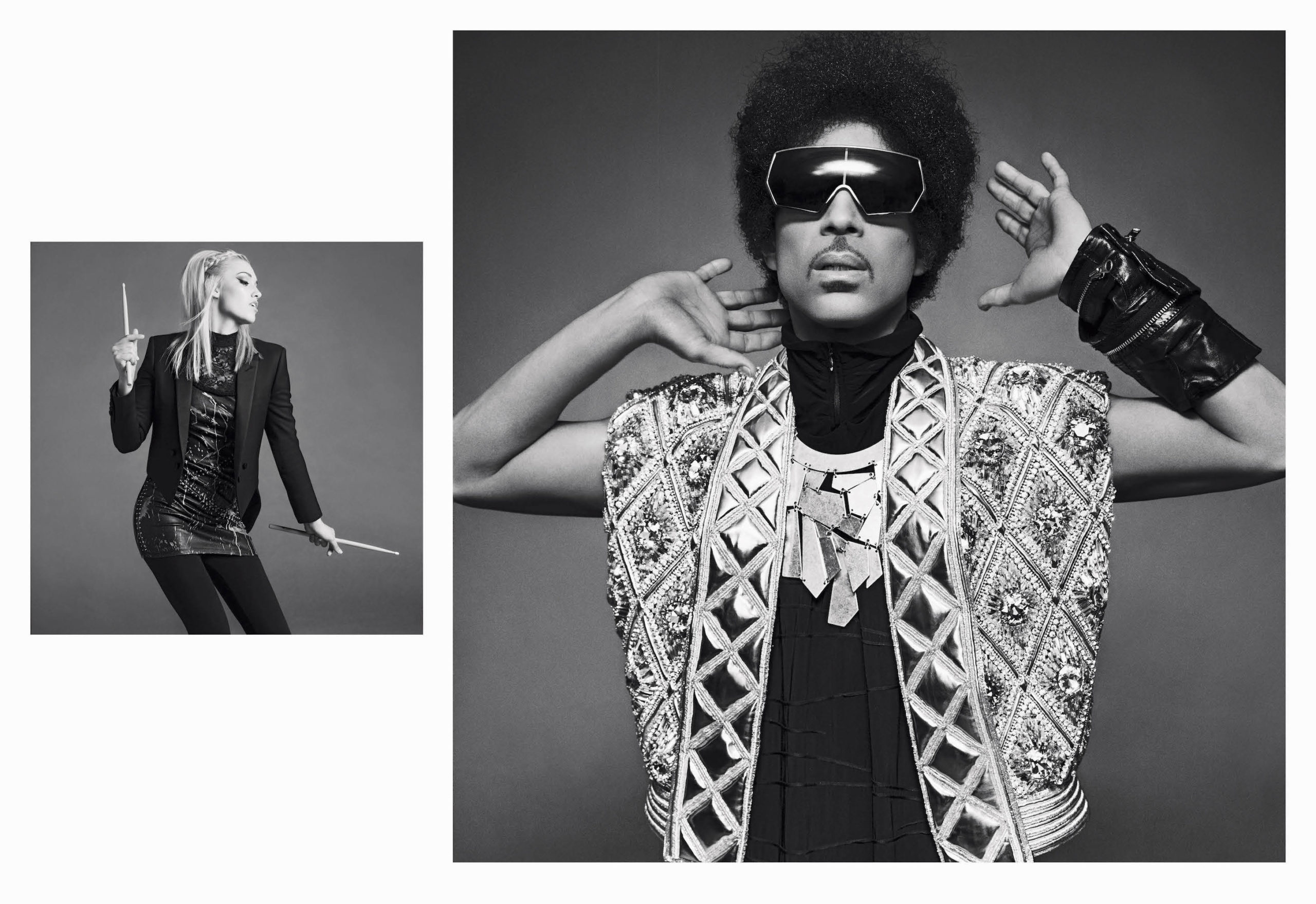

Nearly 40 years into his career, Prince is still churning out mind-blowing music. Currently playing two shows a night while on tour with his new band, 3RDEYEGIRL, the icon takes a moment (at 2am) to sermonize on sex, religion, and rock and roll.

It’s no sweat for Prince to play two sets a night, as he does this evening at the 1,700-seat City National Grove of Anaheim California. He tells me that if anything he’s more energized after the second show, not less. Both shows stretch to a delicious two hours, as the crowd, in blowouts and Vegas-style cocktail dresses (it’s worth dressing up for Prince, even in California), screams and sings along with glee. The only tense moment comes when we file into the theater and a security guard says, “No cameras, no cellphones—don’t even take them out of your pocket. Tonight, we’re not asking, we’re just escorting.” I ask her what that means. “If we see you with your phone out, we’re not going to ask what you’re doing—you’re just gone.”

This demand might seem extreme coming from the Purple One—a very young-looking 55, with a tight Afro instead of his usual loose curls, clad in a black bodysuit with white lines that makes him look like a spider—but in fact it’s not out of character.

You could argue that Prince was an early adopter of phone-text-speak (“I Would Die 4 U” and all that), but he’s eschewed the PR opportunities afforded by the latest tech almost completely, refusing to put his videos on YouTube and offering new music mostly for sale on his websites. And in part by making himself so unavailable, he’s remained as mysterious as ever. Prince has always refused any label the world wants to slap on him. A devout Jehovah’s Witness since 2001, he writes music that is explicit about both Jesus and sexual desire. He’s a black man with light skin who usually dresses in clothes that seem inspired by female icons, from Twiggy to Marie Antoinette. A heterosexual man who deeply worships sexually confident women, he nonetheless wants to dominate them. Prince keeps his private life private: he’s usually either on the road or at Paisley Park, his $10 million compound in the suburbs of his hometown of Minneapolis, with multiple recording studios, wardrobe rooms, a video-editing suite, a sound stage, production offices, rehearsal areas, and “the vault,” which includes his extensive library of unreleased recordings.

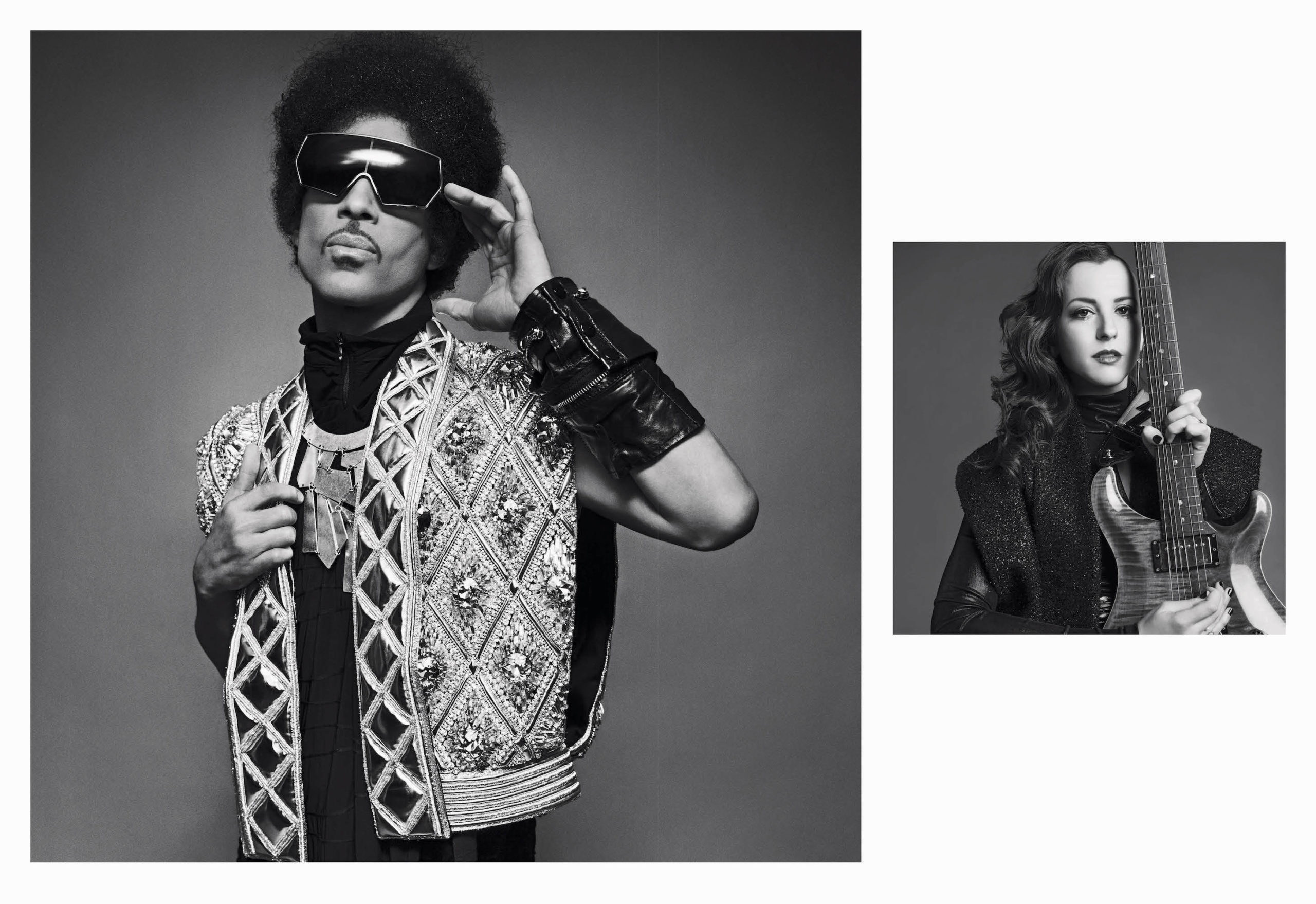

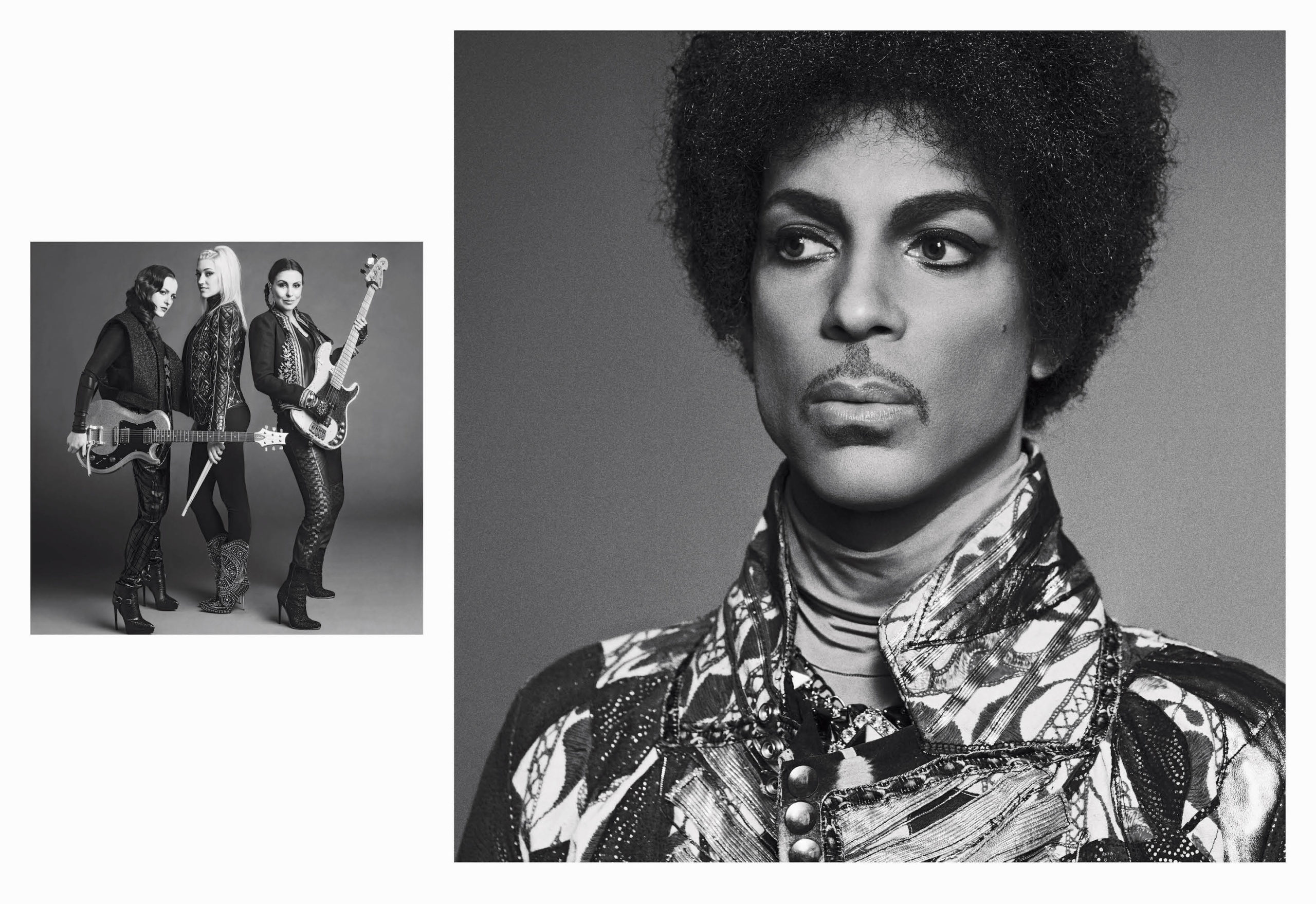

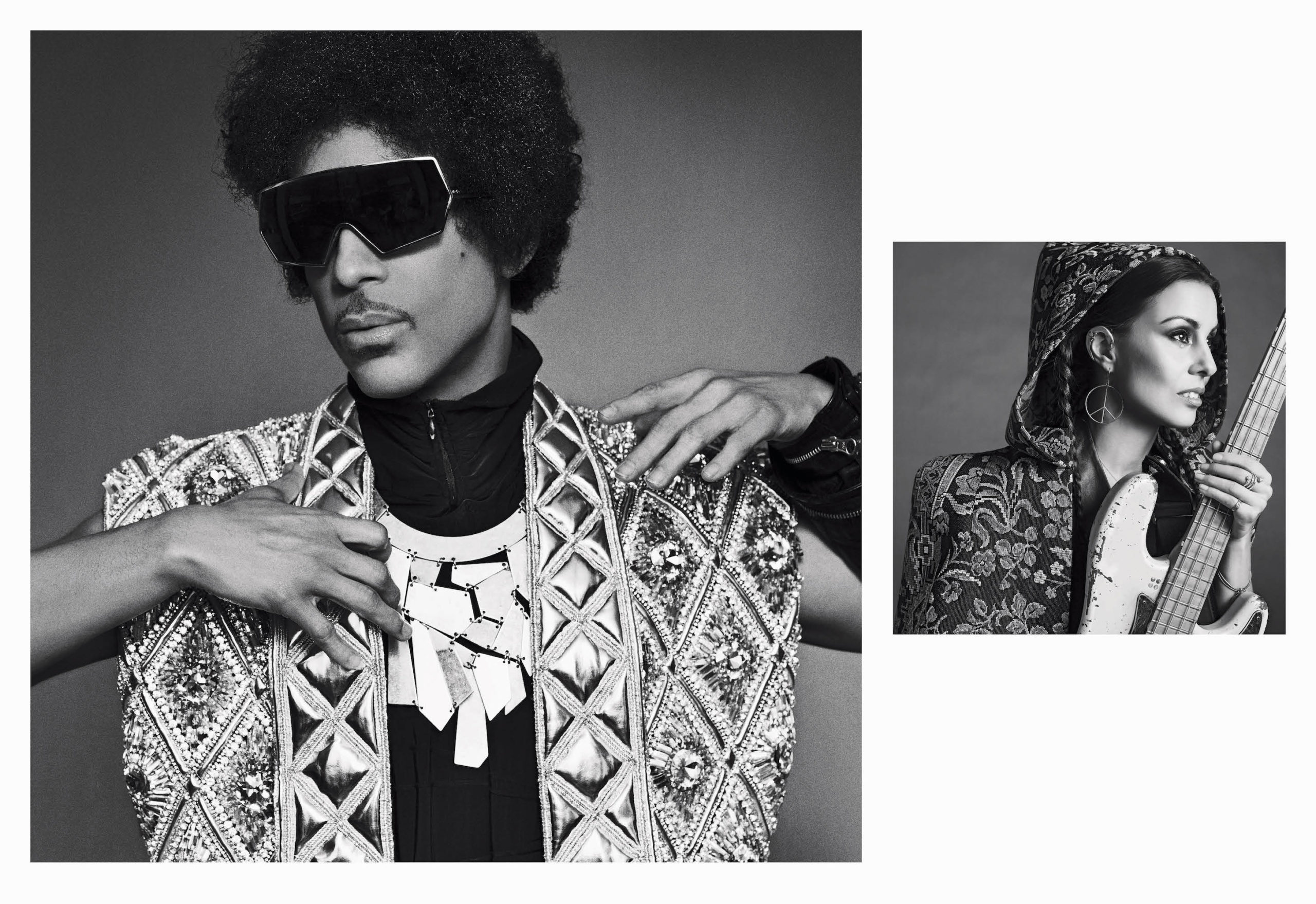

Tonight’s show is a lot less about pop, R&B, and funk than his music has been in the past—in fact, he’s playing rock, like his new song “Screwdriver,” and doing guitar-heavy, stripped down versions of his old hits, including “Raspberry Beret,” “When Doves Cry,” and “Computer Blue,” for which the stage is suffused in blue light. For this tour he’s backed by 3RDEYEGIRL, a new rock band that he assembled himself. It’s made up of Danish bassist Ida Nielsen, wearing pigtails, blonde Chicago College of Performing Arts at Roosevelt University jazz performance major Hannah Ford-Welton, on drums, and Canadian Donna Grantis, with half her head shaved, playing a wild, shredding guitar. “I’m trying to get these women’s careers started, because they’re all so talented,” he tells me later. “It’s not even about me anymore.”

Playing with 3RDEYEGIRL, there’s lots of room for Prince, one of the world’s most celebrated guitarists, to show off his skills (though Ms. Grantis does keep up with him). The show feels like a gospel revival, with Prince as the groovy, feel-good pastor facilitating a release of energy for the crowd, which sings along and nods when he throws out lines about “compassion” or preaches “the only love we have is the love we make—we’ve got to take care of each other, everybody.” At the end of the show he says, “Thank each and every one of you for leaving your cell phones in your pocket. I can’t see your face when you’ve got technology in front of it.” At 1:30 am, as the lights go up after the second show, two MILFs chat by the stage. “He was gorgeous up there,” says one. Prince’s elegant manager, Julia Ramadan, appears quickly and whisks me through a clutch of roadies and onto Prince’s idling tour bus, where 3RDEYEGIRL is hanging out. I’ll do my interviews here, and per Prince’s usual demand of journalists, will conduct them without a tape recorder or notepad, though I am allowed to have a list of questions. When I ask him why he’s required this of journalists over the past decade, he says, “People have sold my interviews.”

First, I talk to 3RDEYEGIRL, who are still flushed with excitement from the shows, about their experience with Prince. Nielsen, who has played with Zap Mama, was the first one he recruited. Prince’s manager found Ford-Welton. Grantis appeared when Prince told Ford-Welton and her husband to discover “the best female musician out there” (they found her videos on YouTube). We talk about what life is like at Paisley Park. “We practice all the time,” says Ford-Welton—it’s something like 12-hour days, six days a week. All the musicians in 3RDEYEGIRL have a background in jazz improvisation, so they’re able to react quickly to Prince’s lead when he’s composing, but they’re still astounded at how fast he is at songwriting and arranging. Grantis calls him the “best band leader in the world.” Nilsson nods. “There’s a special chemistry between us,” she says. Later Prince will ask DJ Rashida to play a banging song for me that he wrote for Ford-Welton and her husband at the after-hours party. I ask Rashida what Prince songs he doesn’t like her to play at his parties, and she says, “Well, not the ones with curse words, because he doesn’t curse anymore.”

Soon the door to the tour bus opens: it’s the man himself. He’s changed into a new outfit of flared pants with primary color stripes, a large ring with a blue evil eye at the center of his right hand (“nothing evil about it,” he tells me) and a rhinestone-encrusted pimp cane in the other. The cane is just for decoration; he is clearly in amazing shape. Prince points at me and then at Richard Sanders, President of Kobalt Music Group. Richard takes out a sheaf of paperwork and puts it on the bus’s kitchen table. It’s the contract for the new 3RDEYEGIRL record, which has been awaiting a final signature. Prince affixes with a flourish.

“That’s it,” he says, turning to Grantis, Ford-Welton, and Nilsson. “You’ve got a record deal. Now we just have to make some songs.” Everyone laughs at this joke—with Prince’s prolific output as a producer, they’ve been recording so much for the past few months that they already have most of the album done. The women take their cue and leave the bus, with Richard hot on their heels. “Thank you so much for coming,” Ramadan says to him, graciously. “Oh, please,” he replies. “This is the fun part.” With everyone gone, Prince and Ramadan take seats on a low-slung black leather couch. I sit opposite and throw out my first question: “I was just talking to the women about your new band, about how they met you. But what drew you to creating the band in the first place?”

Prince rests his thin, elegant hands on top of the cane and speaks quietly—he expended his voice during the shows, and now he’s saving it—but never averts his gaze. Framed by thick lashes, his extremely large, liquid eyes seem to occupy half his face.

He takes a breath and then begins a long monologue: “This organization is different than most, in the sense that we don’t take directions from the outside world. It’s like a galaxy. The sun is in the center giving of energy, and everything revolves around it.” He talks about what it would be like if instead of the sun giving of energy, energy was trying to exert its force on the sun. That wouldn’t make a lot of sense. It would be, he says, like “meteors hitting a planet!” What makes much more sense is “a sun pulling everything around on its own axis, with information. The sun is information. Nobody really talks to me. Nobody talks to me a lot.” He points at Ramadan. “I talk to her. She talks to you. She talks to Richard. And so on and so forth. If I trust her, then you can trust her.”

Prince likes this system. “I directed a couple films and it was taxing in that people were asking me questions about their jobs.” He much prefers peace and calm. “I have to be quiet to make what I make, do what I do.” He takes a breath. “Another thing that’s different about this organization is that time here is slowed down, because we don’t take information from the outside world. We don’t know what day it is and we don’t care. There is no clock.”

Living in the now, he says, makes the tour go by very quickly. Indeed he couldn’t tell me how long he’s been on tour because he only counts the hours he’s actually onstage when he thinks about it. So in the last month, “I’ve only been on tour for two days,” he says. “That’s the work.”

He seems to have come to the end of this thought, so I look down at my questions, unsure if I should ask the first one again. Better not. “Your shows are wonderful, obviously, but known to be very unpredictable,” I say. “How do you decide what you are going to play?”

“I decide in the moment,” he says. “I change the set list right then and there.” He also takes into account the state of his guitar. “To play solos the way I’m playing them, the guitar goes out of tune sometimes. It’s just a piece of wood.”

“What happened with The Roots’ guitarist’s guitar, the one that you threw after your performance on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon?” I ask.

“What?” he says.

“Didn’t you borrow a guitar from him and then throw it after your set? It was all over the news.”

“No,” he replies, straight-faced. “Another thing that’s different about this organization is that we don’t think about that,” he says, pointing at the TV.

He returns to speaking about guitars. Sometimes, he says, he makes sure to include a song he can play on piano so the guitar can go offstage and get tuned. In fact, he explains, this is why he added Gratis to the band—he needed a second guitarist for these moments. “But that guitarist had to be great,” he says. “She couldn’t be a punk.” How does he think female and male guitarists are different? “I don’t think women and men are different in that regard. Donna can whup every man on guitar, bar none.”

What’s the difference between men and women generally?

“Well,” he says. “If we didn’t have to go to a party, we could talk about that.” I see him shifting around in his seat a little—he has planned an after-party in the venue’s VIP lounge—and I start to think he’s going to cut the interview short. So I ask my big question: “How do you, as a religious person, reconcile the religious impulse with what most of your songs are about, which is the sexual one?”

Prince bursts out laughing and points to Ramadan. “Ha!” he says. “Now we know what you’re going to write about. We were waiting for your thread.” He clears his throat. “First of all, do you see a difference in religions?” he asks. I say no, suggesting all religions are based on the same idea and then corrupted by their human leaders. “Then what are the wars about?” he asks, unhappy with my answer. “If one religion believes Christ is the king, and another doesn’t, then there’s a difference in religions.” He goes on for a bit, and adds, “we are sensual beings, the way God created us, when you take the shame and taboo away from it,” and continues that religion should be thought of like a force, an electro-magnetic one or like gravity, that puts things in motion. Then he says, “I don’t want to talk about this.”

I ask him if he believes in sin. “You have to look at the origin of the word,” he says. “Humans needed a language to describe a rule given from some group from…” He pauses, then says, and this is as I remember it: “Words are tricky. And plus these days I just talk to the folks in the outside world about music. If you were a student and I was teaching you something we could get into that. We can’t do this before a dance party.”

I begin madly crossing off my non-music questions and tell him I’m thinking of learning guitar so I can teach my daughter. “See,” he says, “if I discussed my past, your baby would never see you. And what a waste.”

We talk about how he seems to be operating on a business plan that requires him to do a lot of touring. “I love it,” he says. “What, this is so terrible? I’m sooo bored of it.” He gestures around his swank bus and laughs. We discuss which song in his vault he feels he should have released. “Which one of your children do you like the best?” he says. “Music comes from the same source. It’s all the same thing.”

What records does he listen to now? He mentions Lianne La Havas, KING (a female trio he’s worked with), Janelle Monáe, and Esperanza Spalding. “I listen to my friends’ records before they come out,” he says. “Feel me. A record nowadays comes out a year after it’s made. When we make music, we want it to come out right away. Because we’re going to have some new stuff right away.”

What does he feel about the return of vinyl? “It never left,” he says. “Think about a young person listening to Joni Mitchell for the first time on vinyl. You know how fun that is? Whoa, we gonna be here a minute.”

I ask how tech-averse he really is; does he have an iPhone? “Are you serious?” he says. “Hell, no.” He mimics a high-voiced woman. “Where is my phone? Can you call my phone? Oh, I can’t find it.” He talks about people who come to his concerts all the time, akin to the Deadheads. “People come to see us fifty times. Well, that’s not just going to see a concert—that’s some other mess going on. This music changes you. These people are not being satisfied elsewhere by musicians, you feel what I’m saying? It’s no disrespect to anyone else, because we’re not checking for them. But we don’t lip synch. We ain’t got time for it. Ain’t no tape up there.”

He stands up, planting his cane on the floor. I ask how the music that he’s playing now, with 3RDEYEGIRL, has changed him. “I’m calmer now,” he says. “I’m rougher with men. I bring my tone down with women. If they make a mistake, I don’t look at them and go, ‘Seriously?!’” He talks about Ford-Welton missing a cue on one of their songs and how he simply gestured to her and told her just not to do it next time. “I explained that she had to pay attention. Stay in the moment.” Then he smiles. “Let’s go to the party.”