Founded by Alvin Ailey in 1958, the eponymous and groundbreaking institution was always intended to be the opposite of a static museum piece. Not only for the fact that its core discipline is dance, but because, as Ailey liked to say, the pieces he choreographed are blood memories from his childhood in Rogers, Texas. They are love letters to the people he knew and was inspired by growing up, which featured Black narratives. We’re used to traditional ballet with princes and swans, and as an art form that has been historically gatekept. But dance has never been the province of the elite—it encompasses all varieties of love, humor, respect, and dignity. Ailey always said he wanted to “hold a mirror to society.” Audiences to this day attend Ailey shows to see the beauty and the craft, but also to recognize themselves on stage. Dance came from the people, and they’re taking it back.

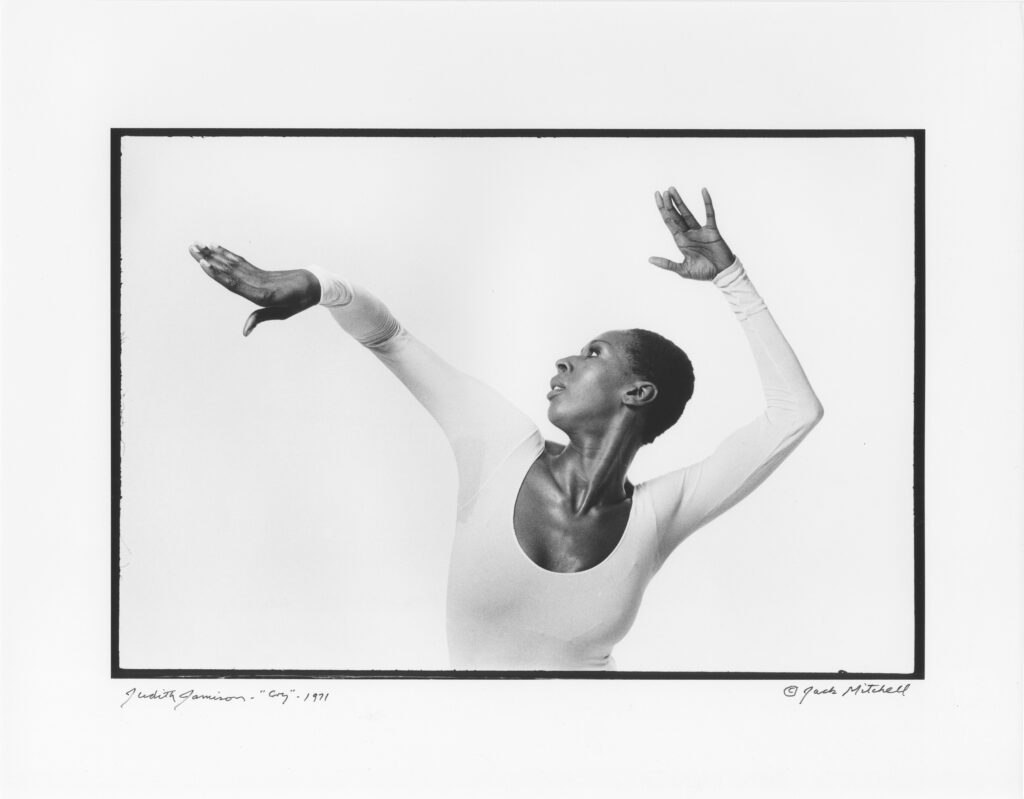

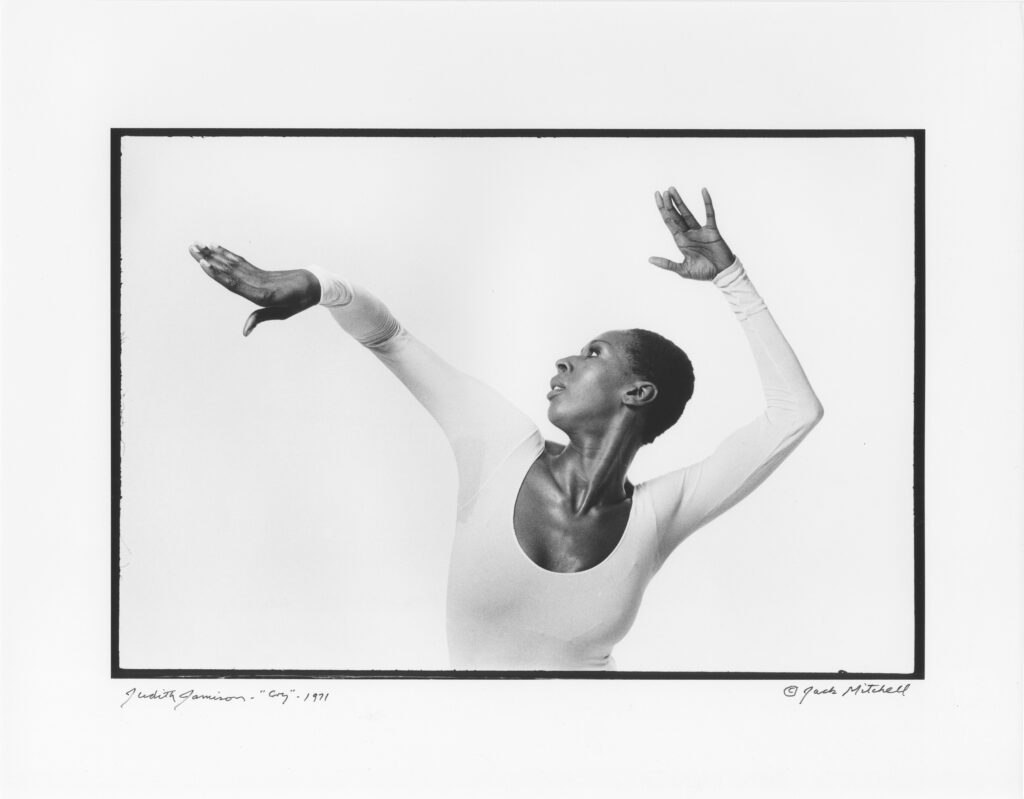

Photo by Jack Mitchell.

(©) Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation Inc. and Smithsonian Institution.

The competitive and precise nature of dance lends itself to perfectionism and, famously, harsh self-critique. Current rehearsal director and longtime Ailey member, Ronni Favors, still remembers being utterly terrified for her first evaluation. To her surprise, Ailey said to her: “Get out of the studio, go to the clubs, fall in love. You have to dance about life. You cannot dance about dance.” This is a lesson she follows to this day and tries to impart to new generations of dancers.

Hannah Alissa Richardson, the female lead in this season’s production of Dancing Spirit, remembers the first time she saw an Ailey show at the age of 14: “I was hooked. There were dancers who resembled superheroes on that stage!” Like many dancers, she feels a strong connection to the morals and values Ailey and his company represent. “Ailey is legacy. Ailey is community. Ailey is storytelling. Ailey is giving back to the people,” she says. Richardson believes that while she’s certainly grown as a dancer in her time at the company, she’s also become a more significant member of her community.

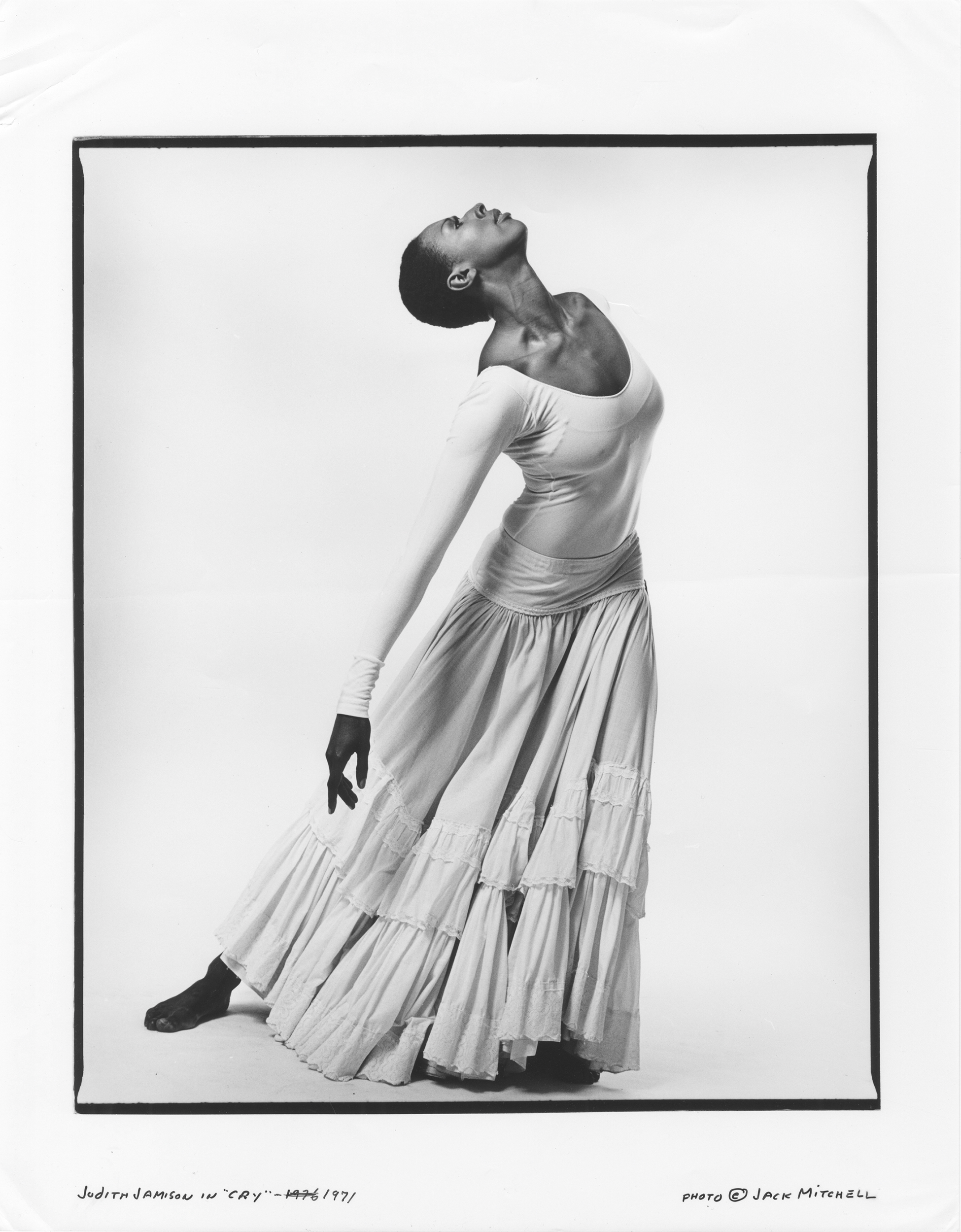

Photo by Jack Mitchell.

(©) Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation Inc. and Smithsonian Institution.

Are You in Your Feelings?, another show this season, focuses on young love and relationships, set to one of the most gloriously nostalgic mix-tapes of soul, hip-hop, and R&B, featuring Lauryn Hill, Shirley Brown, Kendrick Lamar, and Jhené Aiko, amongst others. The female lead, Jacquelin Harris, also remembers the first time she was introduced to an Ailey show—the 1960 classic take on gospel songs, grief, and the Baptist Church, Revelations, which has been traversing the globe ever since. “I grew up Southern Baptist and attended church regularly with my family,” Harris says. “Everything about Revelations, the movement and feeling, represented what I witnessed every Sunday.” Joining the company has offered her the opportunity to experience, in a much deeper way, the cultural impact of Ailey. “Watching audiences digest and love works in our repertoire that highlight negro spirituals, music of Erykah Badu and Drake, and so many other staples really shows me the universal nature of hope, love, and triumph,” she says.

That need for universal hope was never felt more at Ailey than after 9/11, Favors told me. No one was attending Broadway or midtown shows at the time, and yet, the Ailey house was packed every night. Seeing dance gave people a reprieve in an unfathomably lost time. They were reassured that good things in life still existed and that, with community, the bad things could be overcome.

It’s now the 65th anniversary of Alvin Ailey’s creation, and the productions are still focused on purely visceral, life-to-life connections. “This dance, this idea, it means so much to so many people,” Favors shared. No dancer came to Ailey by mistake. They saw a performance and thought, “I want to do that.” Ailey gives young artists a sense of direction and purpose: To hold a mirror up to society and embrace our collective humanity.

This story appears in the pages of V146: now available for purchase!

Discover More