James Sweeney isn’t interested in twins as a party trick or a quirky narrative device. No pastel, copy-paste closets or identity swap hijinks. For the American director and actor (Straight Up, 2019), it’s always been about the darker question. What happens when one half disappears? In other words, ‘What if that was the end of It Takes Two?’

That fascination with individuality, sorrow, and the unbearable closeness of two people who share everything, even reflections, forms the backbone of his latest project, a black comedy in which two men grieving the loss of their twin brothers meet in a bereavement group and form an unexpected friendship. And if that sounds heavy, it is, but it’s this gallows humor that Sweeney insists on even when writing about tragedy (which he asserts with a deadpan delivery).

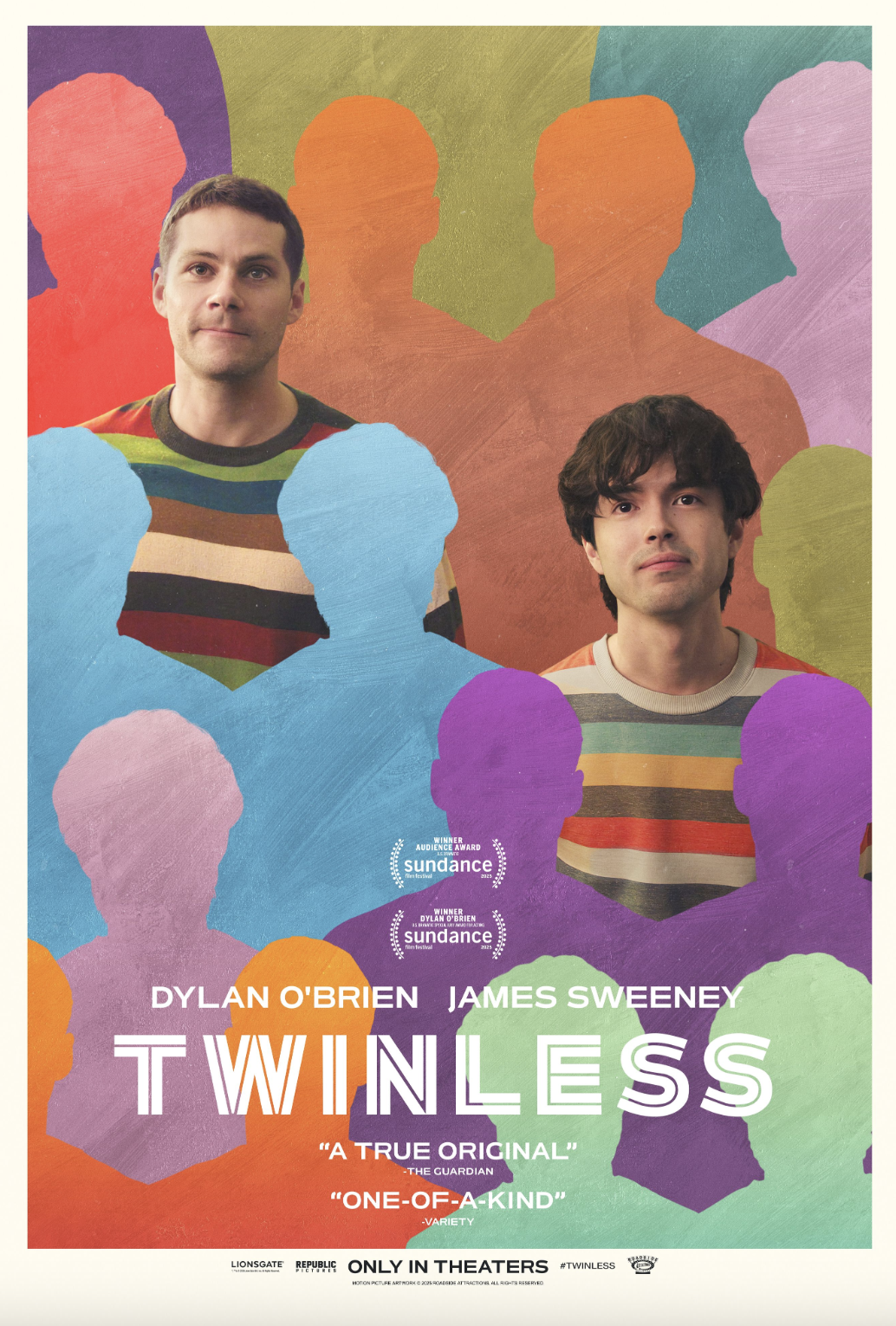

Twinless stars Dylan O’Brien alongside Sweeney, himself. O’Brien, who in recent years has been slipping out of the glossy, franchise-ready roles that defined his early career, has been carving out space in the indie world for a lot longer than most think. Watching him play Rocky, one half of Sweeney’s complicated, searching duo, it’s evident the actor is not an indie novice, displaying a cultivated talent for risking the customary in pursuit of honesty. And although he’s aware of the gap between how audiences see him and what he’s actually trying to do, he seems more amused than resentful about it.

Both men are sitting in a white porcelain bathtub when discussing the release of their upcoming film. Clothed, of course. If Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Marat is any indication of what happens when artists and full tubs mix, it seems Sweeney and O’Brien made the right move in draining it first. Situated on either side of a gold-plated faucet, the actors deftly navigate the current landscape of modern filmmaking, industry pigeonholing, and the complexities behind portraying a gay man in today’s cultural climate.

V Magazine: Can you talk a little bit more about why your affinity for twins comes in the form of bereavement and grief?

James Sweeney: I guess when I first heard of the concept of a bereavement support group, it just struck me as an intensely tragic thing. I feel like it’s the saddest thing I’ve ever heard in my life. I think of like twins that I had an admiration for growing up, and I would imagine, ‘What would it be like if they lost their twin match?’ What if that was the end of It Takes Two? And wouldn’t that be a fucking tearjerker, you know? I’ve always been interested in twin psychology, and I felt like this theme was so rich for exploring identity, which is something that I’m really interested in exploring in my work.

V: Dylan, lately you’ve been undergoing a major career shift, seeking more Indie-driven films. What drew you to that genre as a whole, and then to Rocky and Roman’s characters specifically?

Dylan O’Brien: It’s funny because when you start in the industry, you’re just trying to get a job. You don’t start with a sense of control, so oftentimes the things that you start in—and if you’re lucky enough, succeed in at any level—people may associate you with them. But they’re not necessarily painting such an accurate picture of what you would be going out to seek. I keep getting this question, and I guess it intrigues me because to me, I’m doing so many things that I feel are so abundantly who I am as a creative person. I understand that maybe people don’t necessarily have that view of me, based on the stuff that I’ve starred in—not that those weren’t meaningful things to me as well. I’m really inspired by things that I haven’t done. I’m really drawn to things I’m not seeing as a consumer, as well. I love to see original, fresh things, especially now amidst this rebooting thing. I mean, I get it. It’s a business. For me, I’m like, ‘We’re just going to watch the same movie for the rest of our lives?’

[At this point, I confess that his speech has parallels to Seth Rogen’s rants in Apple TV’s satire on Hollywood, The Studio.]

Oh my god, no. No, no, no, no, no, no.

I’m trying to, as much as I can, pair with voices that I find exciting and material that’s challenging to me too.

JS: Dylan and I initially met in 2020. At the time, he hadn’t starred in as many independent films and was coming off two major franchises. I’ve seen my film not get made, and so many other independent films that he has gotten made—going from Flashback (2020) to The Outfit (2022) to Maximum Truth (2023). He has been consistently doing independent films for years now, and he started in independent film—not a lot of people know that. I understand that he has a very independently spirited mind.

V: The film was, at times, very laugh-out-loud funny, and it seemed like certain ad-libs were improvised. At the same time, you dealt with a lot of grief and even a thriller-like tension. Was there one specific tone you were trying to maintain throughout? How did you mesh everything together?

JS: In terms of improvisation ratio, it was probably like 90%, 95% scripted. But, I love that if you think more, that’s the idea. You want it to feel alive, like it’s off the cuff. In terms of balancing the different tones, honestly, that was a concern. You write the film three times, once on the script page, again when you’re filming it, and then again when you’re editing it. And I tried to hire, both in front of the camera and behind the camera, a team of people who really understood that we were going to be flexing different muscles. We’re trying to make sure it’s cohesive, but also show the spectrum of emotions. It’s a film that I wanted to take the audience on a whole journey.

I also feel like that’s life. We don’t exist in one genre, and if the film incites so many different emotions in people, then I feel like I did my job. That makes me really happy.

V: It may not have fully developed, but you’ve mentioned the use of a ‘gay scale’ to guide Dylan’s performance playing Rocky. How did you go about that? And Dylan, how did you deal with making that character as authentic as possible?

JS: I think the gay scale was really just a shorthand for us, that was an easy way to succinctly express and give it direction. It was based on a larger conversation with a lot more nuance and context. It’s kind of hard to explain in a soundbite for an interview.

DO: It was more like a ‘permission scale.’

JS: We had a lot of conversations about what it means to be a gay man in contemporary America, and what dating is like, and the spectrum of performative masculinity versus femininity, and how that can also shift in certain environmental contexts and maybe present differently when you’re getting into a taxi versus when you’re fucking somebody. I just wanted to make sure it felt authentic.

DO: And the space of my being a straight person performing a gay character—I think there are a lot of opinions that have ebbed and flowed about that in the industry. James and I have our own opinions about that. James, as a gay man, me, as a straight man, we’ve had a lot of conversations about that.

Any type of femininity, or somebody embracing their femininity, is associated with sexuality as well, for young men. I think it’s why you see so much more commonly straight men suppress those feminine qualities, and that’s become a habit. We recently entered this point in the industry, even just five, ten years ago, where it was like, maybe a straight actor might be terrified to play a… what’s the word?

JS: Flamboyance?

DO: I was thinking of something else.

JS: A twink?

DO: No, no, no, no. I’ll think of it. There might be hesitation to bring out femininity in portraying a gay character out of fear that they would be criticized, that that’s just stereotypical thinking. You don’t want to play into a stereotype, right? So that was what we talked about a lot. I think that’s a much more realistic version of the conversation of the ‘gay scale’ than how it was presented in a headline once. And I’m really happy that we didn’t shy away from that, and we portrayed him in a way that did feel authentic.

JS: To give you more credit, it wasn’t just qualities of femininity that you breathed into Rocky that made him so authentic. You so deeply understood who this person was. I remember when we were filming those scenes, I was honestly blown away by how transformed you were. Anyways, I’m just going to pat him on the shoulder.

DO: It’s an openness in his sexuality, not just him being an open sexual person. It doesn’t matter who he happens to be attracted to. He’s somebody who knows himself, and that’s so infectious. That type of personality, to me, has always been so alluring, and I was so excited to play someone like that.

V: So, who came up with the Chubby Bunny marshmallow scene? How did you pull that off?

JS: Yeah, that was the first time I learned Dylan had such a gag reflex.

DO: It was written in the script, so it did come from James. My whole life, I’ve had such a sensitive gag reflex. I’m a guy who, as a kid at the dentist, is crying. So, in the movie, the scene cuts out on Roman spitting them all out, gagging on them, and that’s real. It’s such a nice moment to see Roman with the comfort that he has and shares with Dennis.

V: There wasn’t a clear bad guy or a good guy or anyone who got off scot-free. Was that intentional? What were you expecting from the audience’s interpretations of each character?

JS: There was a higher expectation that more people would be repelled by Dennis, just based on the feedback we had from over a hundred financiers passing on the script. But, I’d say it’s actually been really lovely how many people—even if they don’t personally relate to Dennis—at least empathize or understand why he makes certain decisions or goes to such lengths. We can understand loneliness.

V: Was there anything that shocked you about the reaction to this film?

DO: We had such a hard time getting anybody to have the confidence to make this movie, to put up the money to make this movie. We loved it and had such a belief in it, but I think we were certainly not expecting it to be for everybody, for there to be more of a divisive reaction. So, it’s been so hope-inducing to see everyone have such a positive response.

JS: And also, for people to respond so specifically to all the things that we specifically love. It’s like, ‘Oh, you want more original films? We want more original films! You want more films that travel through different dramas? So do we!’ All the things we’ve been getting such nice compliments for, I was like, ‘Where was this the last four years?’

DO: And again, the tonality of the film is such a tightrope. In terms of the narrative, both of these characters do things that a person may deem unforgivable. The fact that we’re seeing so many people have an understanding and empathy for what each of their experiences has been is so beautifully optimistic.

Discover More