HISTORY OF THE MALE SUPERMODEL

Chances are you can name a handful of current women supermodels. But can you call to mind the name of a single reigning male supermodel? Believe it or not, there was a time when Jeff, Cameron, and Marcus sounded a lot like Kate, Linda, and Christy. Writer Tim Blanks charts the rise and fall of…

The preternaturally blue-eyed, level stare of the young man in Gucci’s Pour Homme II fragrance campaign is striking in its dare-you audacity. In modeling terms, it’s so memorable it ought to be a star-making turn. And yet who—aside from visitors to models.com and, perhaps, readers of this magazine—would know that Gucci’s blue-eyed boy is Mathias Lauridsen? or that the Dane is currently number one on models.com’s ranking of the top fifty male models?

That may be an unwitting illustration of what the website meant when it once made reference to the standard mannequin’s “genius for anonymity.” While it’s true that there are those who would insist that the women’s modeling world has been overrun lately by faces with the same knack for “sameness,” Lauridsen’s counterpart on the ladies’ chart is Gemma Ward, and the star-making machinery of the fashion industry has invested much more effort in her profile than in his. Traditionally, modeling has always been a woman’s world—economics and simple psychology have conspired to make it so. Women feel much more comfortable looking at pictures of other beautiful women than men do at pictures of handsome men. Men respond more to achievement (athletes and actors) than good looks—or they prefer the regular guy. There was never the need—or the appetite—for reinvention that made women like Linda Evangelista and Naomi Campbell into media sensations. Moreover, throughout history, artists and their audiences have been mesmerized by the transience of female beauty. The dark sonnets, Dorian Gray, and Death in Venice aside, beautiful male muses seldom muster that much inspiration. the consolation prize? We’re constantly assured we age better.

The radical change of guard in the 21st century did little to affect the big picture. Raf’s and Hedi’s models may have been shock troops of a new menswear sensibility, but their idealized boyishness was a deliberately anonymous affront to the male status quo. You couldn’t put a name to any of these pubescent faces. On a positive note, they have contributed to the fade-out of male modeling’s most insidious myth—the one about male models being sexually ambiguous and/or stupid, forever known as the Zoolander effect. Ben Stiller’s satire did, however, pay tribute in its own backhanded way to the durability of another myth. The idea of the male supermodel persists, even if it’s mainly in the imaginations of the models.com-unists. It’s an odd echo to a semi-golden age of male modeling, when the goalposts shifted and when the myth was almost made flesh.

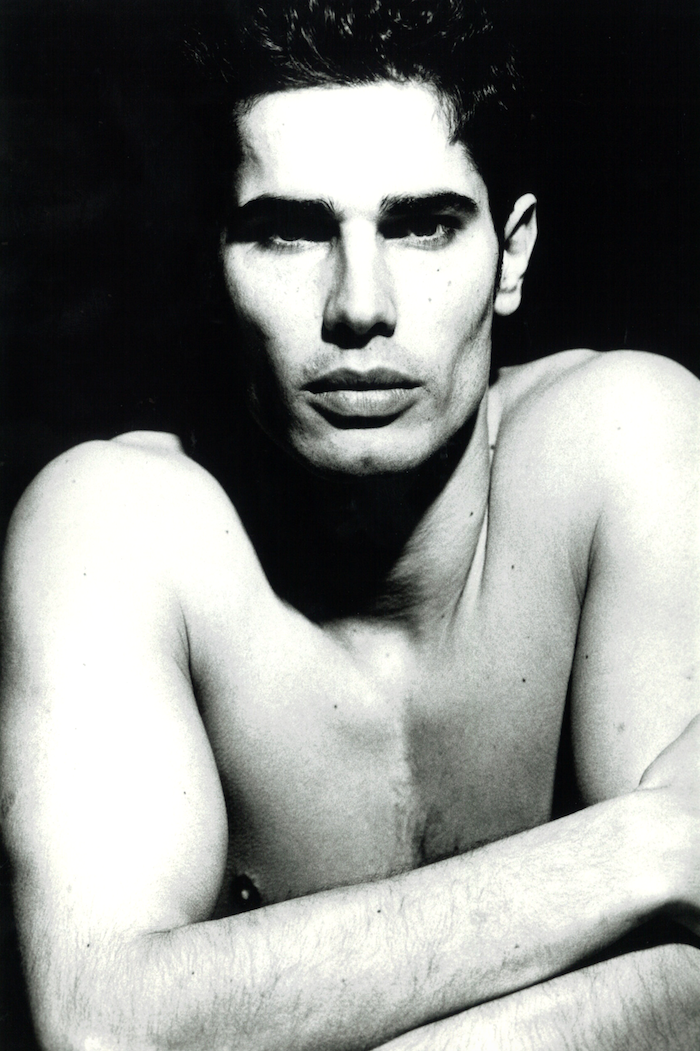

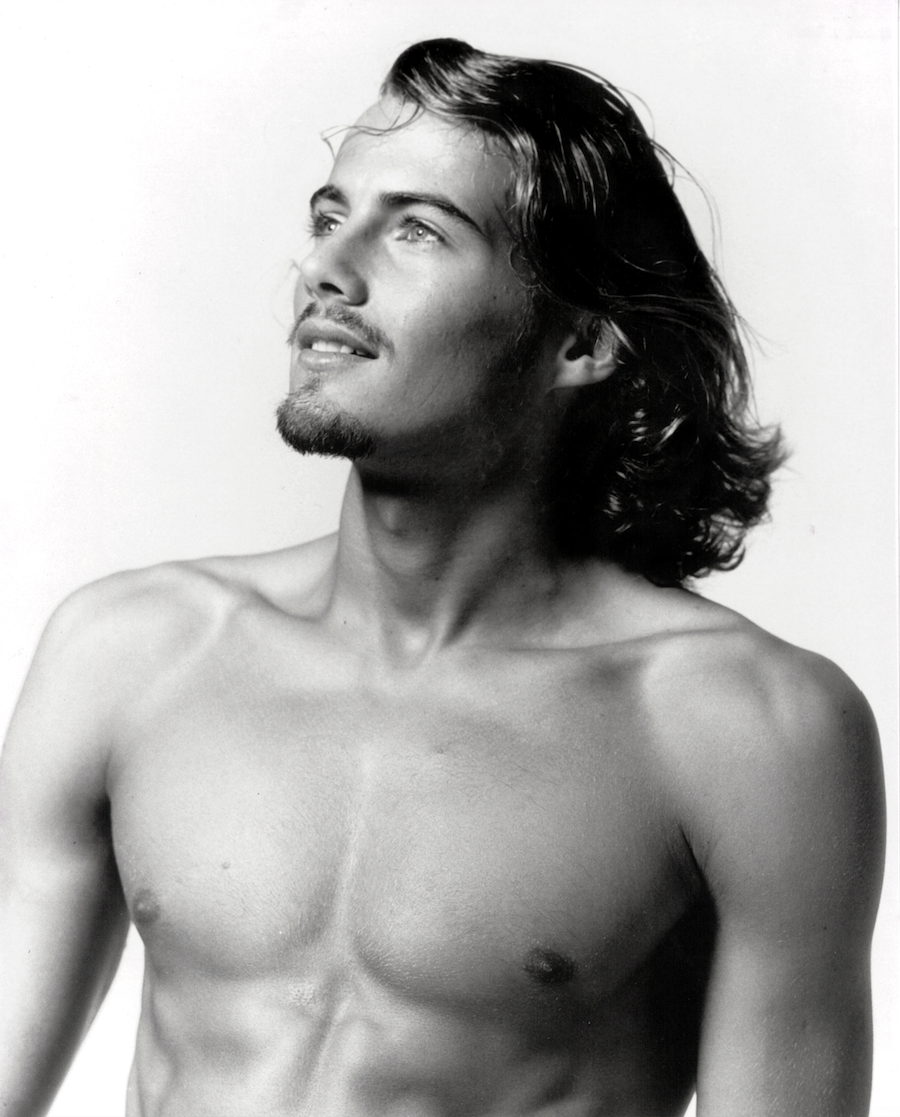

It began in December 1978, when the Soho Weekly News ran a portfolio of images by a relatively unknown photographer named Bruce Weber. His subject was Jeff Aquilon, a water polo player from Pepperdine University. The pretext was an underwear shoot; the subtext was an intimate, erotic reverie that was startling in its narcissistic intensity. If the content wasn’t exactly new (you could find limpid male nudes throughout the century in the work of Baron von Gloeden, Herbert List, and George Platt Lynes), the context was. Until Weber shot Aquilon, male models were men like Joe MacDonald, square-jawed paragons of unambiguous masculinity. Weber proposed a different kind of male ideal—ambiguous, submissive, sensuous—and the unabashed homoeroticism of this proposal flipped the lid on the hidebound way men were depicted in the media. Man as sexualized object was the linchpin of gay porn, not mass culture. Weber legitimized the notion for the mainstream, amplifying narcissism as the soul of male sexuality, gay or straight. And, no question, Aquilon made a stunning poster boy. From the 21st-century vantage point, he looks like the natural evolution of an earlier male pinup, Joe Dallesandro, who insinuated a whiff of polymorphous perversity into pop culture at the beginning of the ’70s.

But Dallesandro’s vehicle was the underground movies coming out of the Warhol factory, whereas Aquilon captured the popular imagination in the most overground way imaginable. His vehicle became Calvin Klein campaigns in mass-market magazines and times square billboards. Aquilon (at least as Weber depicted him) was a male harbinger of the ’80s: surface gloss, idealized flesh, fetishized beauty. He was the advance guard of the Weber revolution, in its day as significant a reevaluation of the male image as Raf Simons’ aesthetic would be two decades later. Of course, you’re saying, Jeff who? Photobooks and magazine retrospectives testify to the allure and influence of bygone female models, but their male counterparts remain consigned to the sidelines of fashion history. Still, they had their moment in the sun–or rather, on seven-story billboards in Times Square. That’s where Tom Hintnaus, the Olympic pole-vaulter weber scouted after Jeff Aquilon, ended up in august 1982, in a pair of Calvin Klein tighty whiteys. Weber and Klein stuck their envy-inducing adonis front, center, oversized, and underdressed in what should have been a spectacularly subversive piece of public art. Instead, it was merely brilliant commercial timing.

The blossoming of gym culture in the early ’80s meant middle-American manhood was primed for self-regard, ready for sculpted abs and pecs. As star athletes, the new gods found acceptance instead of sidelined rejection. In 1984, Aquilon released a workout book with Nancy Donahue, his wife at the time. Far from reactivating the locker-room insecurities of average mensches everywhere, he and Hintnaus were icons of male aspiration. For all their natural assets, they were just reassuringly regular guys—all-Americans, in fact, which in the end defused the threat posed by Weber’s homoerotic idealization. If it was a remarkable balancing act on the part of all concerned, it nevertheless denied the possibility of the cult of personality, which would spring up a few years later around women like Naomi, Linda, and Cindy. It was missing the key ingredient…glamour.

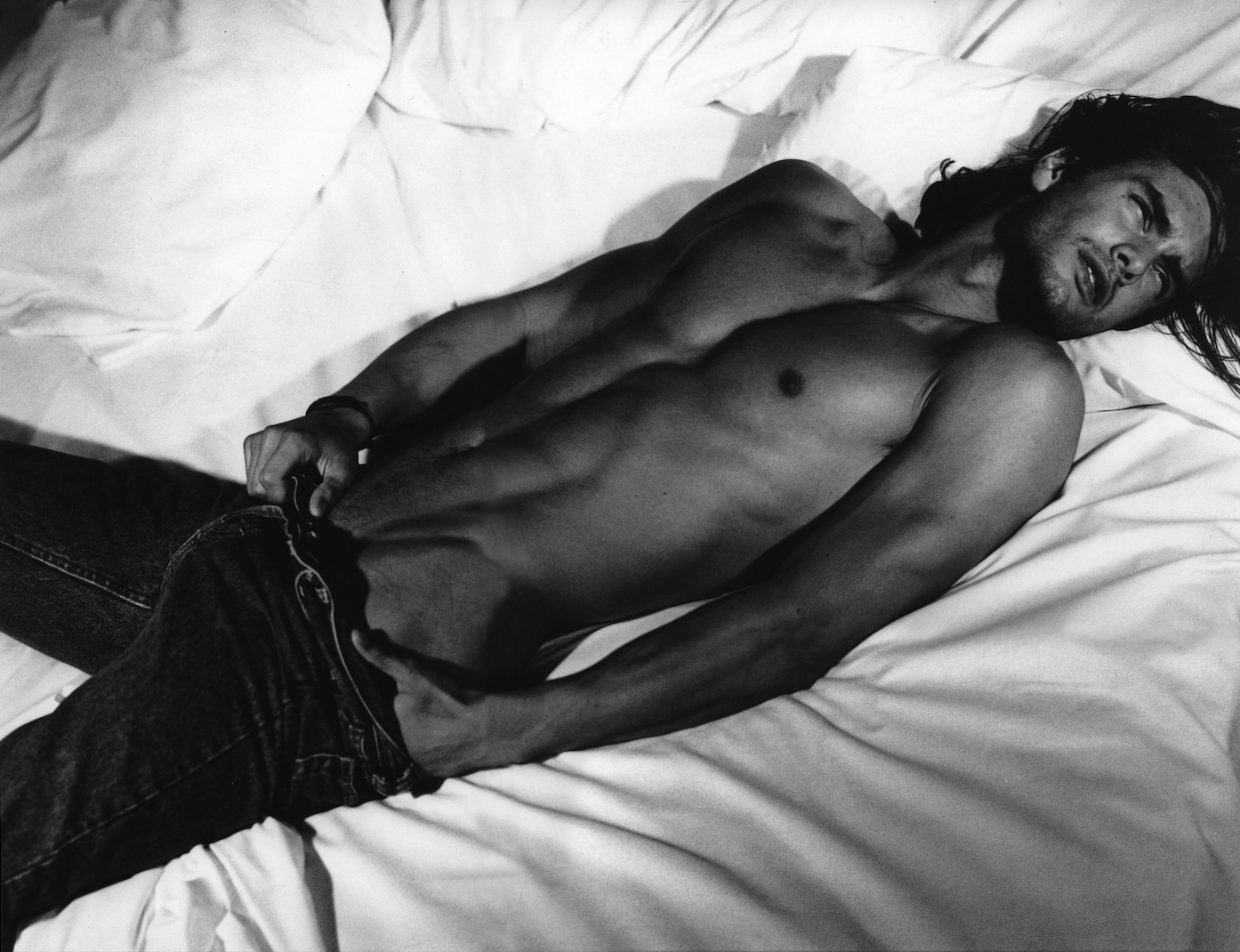

It did, however, inspire imitations and reactions, all of which took Weber’s implied threat as the starting point. In England, stylist Ray Petri shaped a confrontational, highly sexualized, and far darker male aesthetic, which, as the optimistic momentum of the ’80s began to stall toward the decade’s end, insinuated itself into the mainstream. Persian Cameron Alborzian and American John Francis were its main ambassadors. Hard boys for harder times, they looked like something that had sauntered off Jean Genet’s waterfront—anyone’s for the right price. Provocateurs like Gaultier and Madonna couldn’t get enough of them (that’s Cameron in the video for “express yourself”).

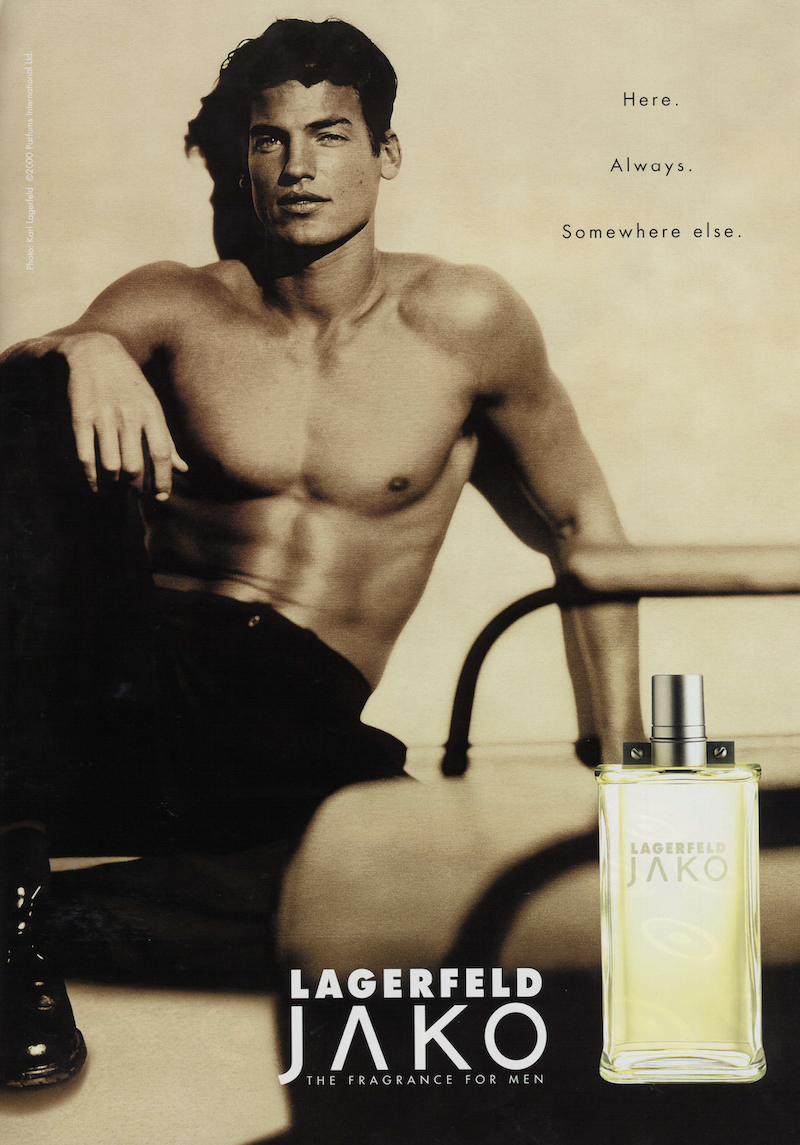

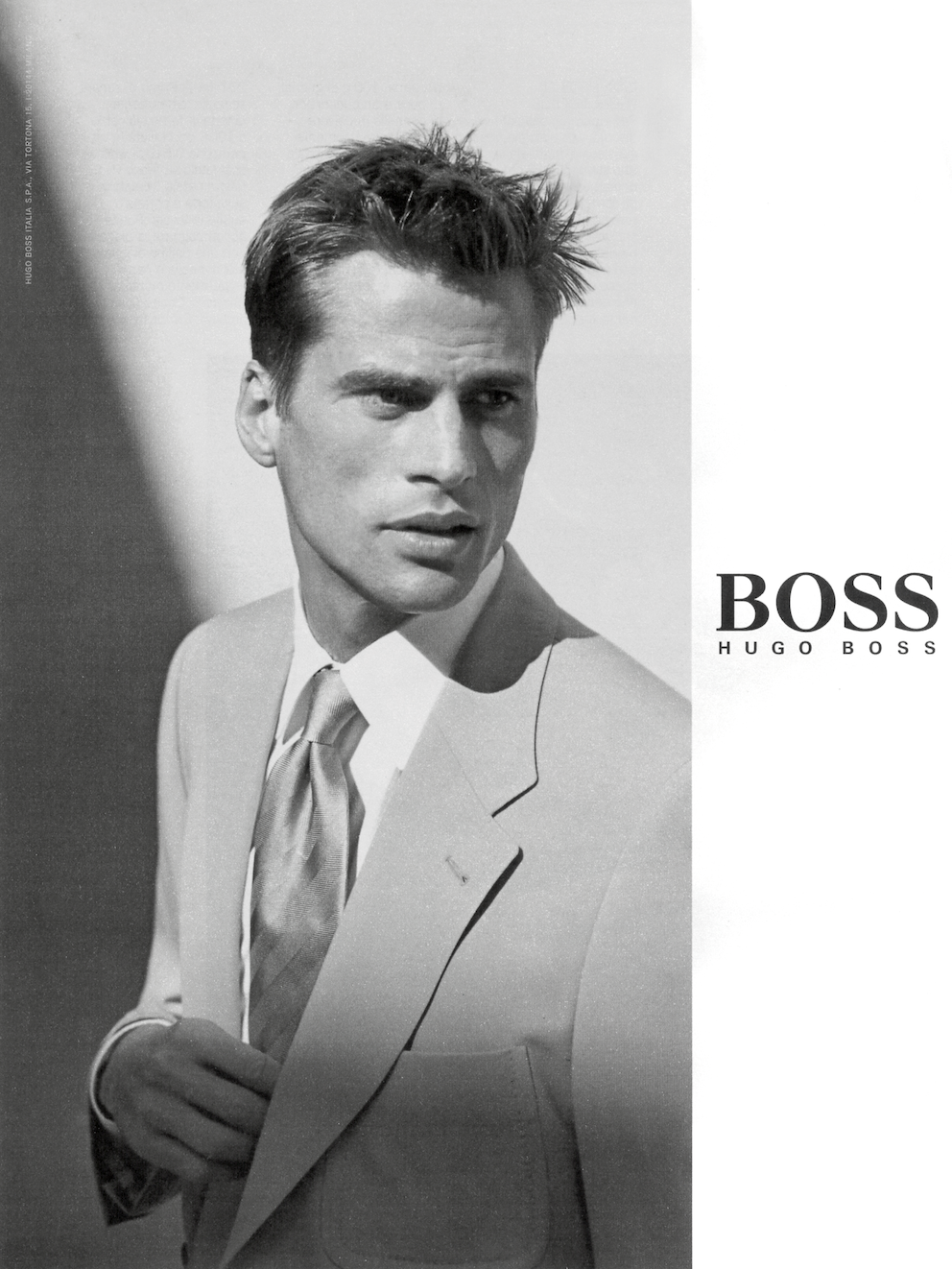

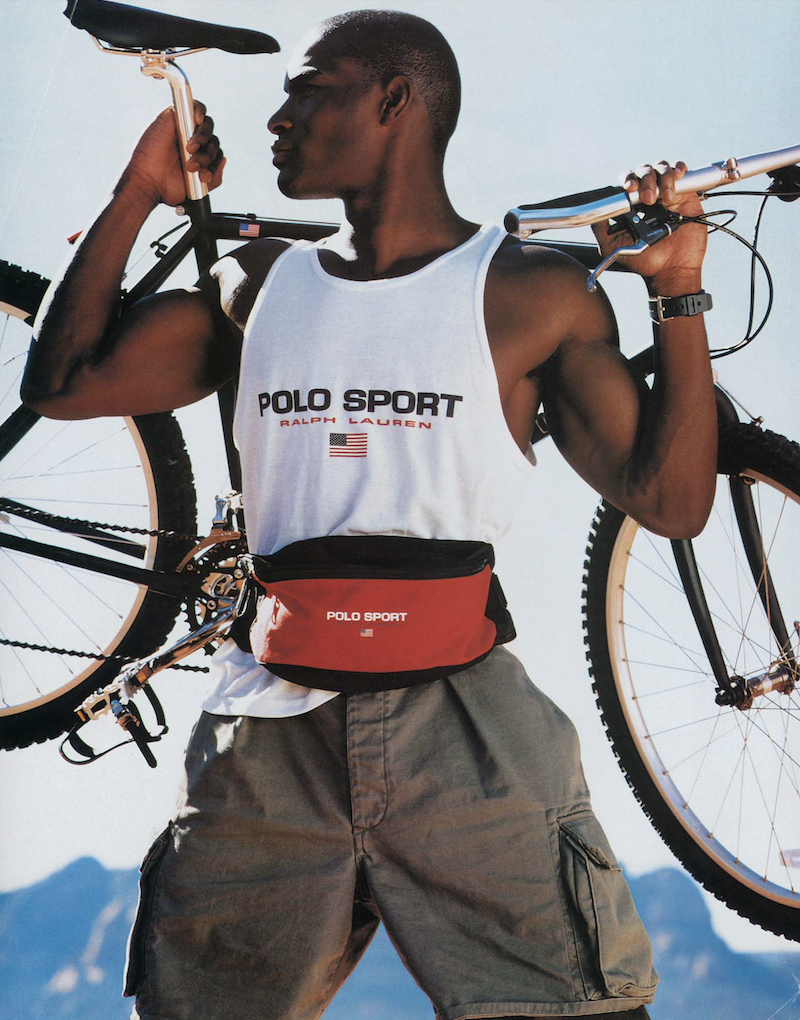

Alborzian and Francis were the exotic, erotic, dangerous antitheses of Weber’s original male thesis. And what happens when thesis meets antithesis? Marcus Schenkelberg, Alex Lundqvist, Mark Vanderloo, Tyson Beckford, Joel West: this time, the idealization of Weber wasn’t softened by the regular-guyness of his subjects. With the success of the female supermodels as an inspiration, there was a more acute sense of what opportunities might exist for male models who were prepared to indulge the fantasy a little more. So this early ’90s wave of male archetypes was familiar- but-foreign, straight-but-pliant, mainstream-but-edgy. And, in this period, men were tellingly marketed for the first time as “supermodels,” with incomes vaguely commensurate to, say, a second- or third-tier female model.

The fact that the idea of the male supermodel didn’t really take at this moment, which was as ideal as it would ever get, was the final kiss-off for the concept. The media fascination with Schenkelberg and Vanderloo depended on how much they were making or who they were dating, and neither situation was built to last. It even happened in menswear that designers no longer wanted “faces” stealing the thunder of their clothes. Here a “genius for anonymity” could become a distinct asset. As for the models themselves, they seemed perfectly happy to come and go, back to cartooning or architecting or student- ing or driving forward onto Hollywood. Mark Vanderloo tried reinvention by going shaved-head-porny-hardcore for a Steven Klein shoot for Arena Homme Plus in spring 2000.

As for Jeff Aquilon, Bruce Weber revisited him for L’Uomo Vogue in October 2006. He lives with his wife, Stephanie, and four kids in Santa Barbara, where he teaches computer technology at Westmont College. Not exactly the lion in winter. In fact, you could say his is more of a model existence than a model campaign. So maybe regular guys do finish first, and so who needs the audacious blue-eyed stare after all? Tim Blanks

*This essay is from the pages of VMAN9 Fall/Winter 2007

Discover More