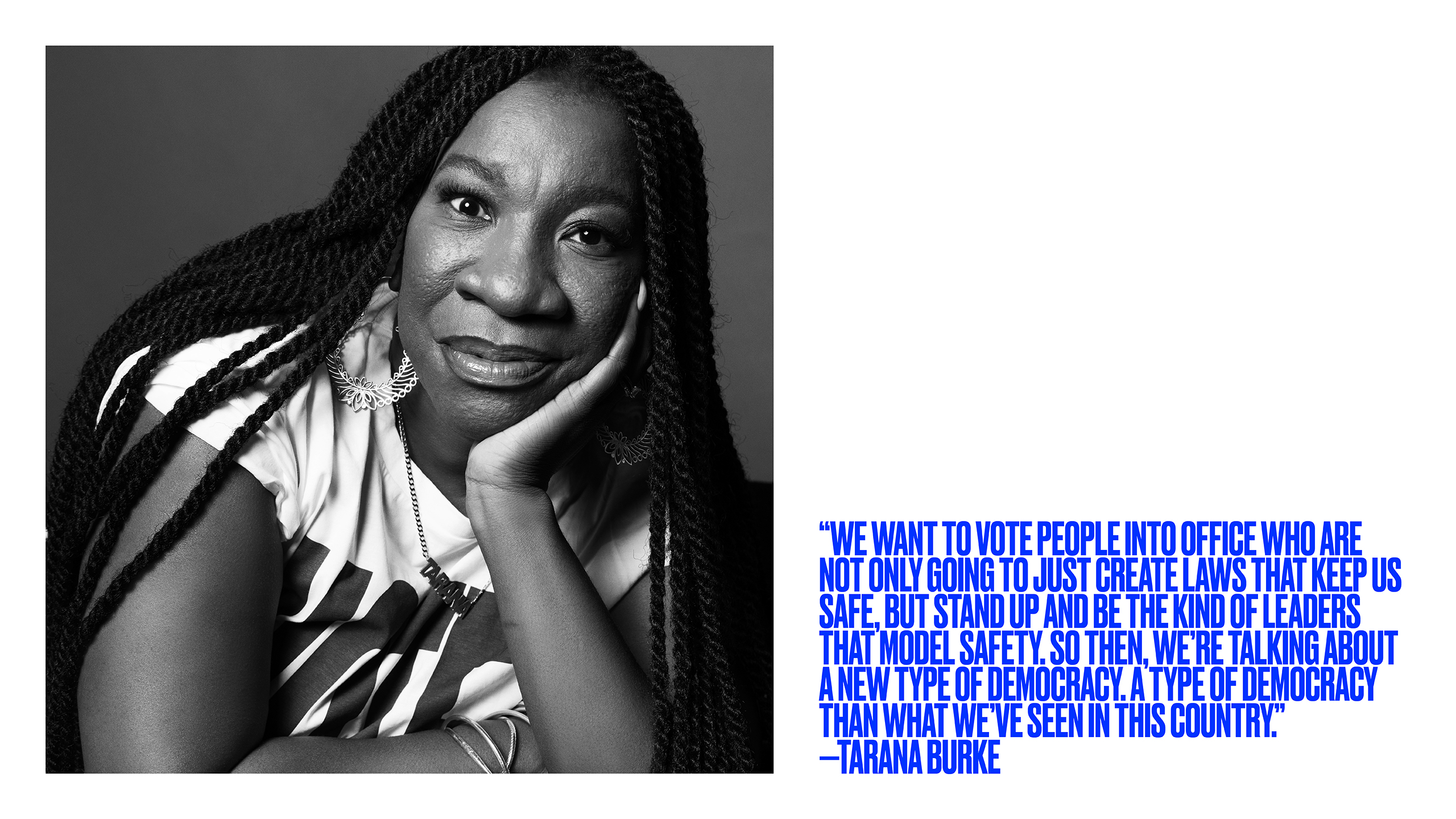

Midterm Elections 2022: Tarana Burke

The founder of the #MeToo Movement asks how we can build a democracy of social justice and safety

Flashback to 2017, when you were first scrolling on Twitter and saw a friend, a colleague, or a celebrity post that famous hashtag: #MeToo. Those two words formed a movement, and an underlying community for survivors of sexual assault to support each other. Never has there been such visibility for sexual violence in the American spotlight. Behind the scenes, it was Tarana Burke who was laying the groundwork for this mass-media campaign. There would be no #MeToo without years of work on Burke’s part, making her one of the leading activists of the modern era. Burke’s work has helped thousands of people to feel whole, feel welcome, and feel true, and beautiful in their present lives.

With the 2022 midterm elections upon us, Burke wants everyone to know how important politics are to social justice and sexual empowerment. With bodily autonomy being excised from our everyday rights, Burke emphasizes just how important the present political moment is for maintaining our everyday humanity. Social movements can create a community for survivors, but changing our politics and institutions is the only way to stave off the issue of sexual violence. And there’s an immediate step you can do to aid the cause: go vote.

See below for the full conversation with Burke and climate activist Saad Amer below.

Saad Amer: I wanted to expand on some of your experiences and the depth of organizing that you do for #MeToo. It’s rooted in so much power and privilege, and in many ways, our democracy is too. Can you tell me about those parallels and how voting is relevant to the #MeToo movement?

Tarana Burke: Well, one of the things that I have been trying to get people to see is survivors are a voting block. What if we, for a second, thought about survivors as people who voted along their survivorship? Not as a Democrat or a Republican, not as a laborer, but just along the lines of their survivorship. We’re talking about an enormous voting block. And what if we voted along the lines of, we want people who are going to reimagine safety. We want to vote people into office who are not only going to just create laws that keep us safe, but stand up and be the kinds of leaders that model safety. So then we’re talking about a new type of democracy. A [different] type of democracy than what we’ve seen in this country.

SA: We’ve seen so many conversations about bodily autonomy really come to the forefront in the last few months. I’d love to know your thoughts on the recent Roe v. Wade decision and how that ties into your work and into this election.

TB: This is not an issue that can be separated from that. I think that we have to know that the Roe v. Wade issue is inextricably linked to so many other issues across the board, because it is about bodily autonomy. It’s really about our human rights. I think that if we start trying to make it really small, then we lose the bigger issue here. Once you start taking away issues like bodily autonomy, it’s like a gateway drug. It’s a gateway into taking away other human rights issues. And if we don’t pay attention to the issues like this, then we will allow the space for the people who want to take away our larger rights–it gives them wiggle room to start going in and taking away everything else. And they’re already laying the groundwork for that. This is just a cog in the wheel. It’s just a piece of the puzzle to start eating away at our other human rights, which they’re already doing.

SA: How do you think about intersectionality in this conversation?

TB: You cannot talk about these things separately. I try to get people to see, this is why you have to talk about sexual violence as a social justice issue, because they’re all inextricably linked. I try to get people to see as the larger picture. When people talk about sexual violence, they talk about us as survivors, as individual people who just need social work. It’s social work as opposed to social justice. So it’s like, “Oh my gosh, you had this thing happen to you? Have you sought therapy? Have you gone to the doctor? Did you call the police, you individual person who needs help?” And they don’t tie that to larger, deeply rooted issues of social justice. There are systems in place that allow that violence to happen. And they’re not just institutional systems, these are cultural systems that are in place. We have to shift the culture that allows this violence to happen, and that culture is deeply rooted in our institutions. So all of those things have to work in tandem in order for this violence to happen. Rapists aren’t just born. Institutions create them, culture creates them, and then that violence happens. Those people aren’t born bad, they are cultivated by culture. They are created by institutions. So we have to uproot the culture, and we have to dismantle institutions. Which is why I keep trying to get people away from looking at the outcomes of court cases and the taking down of individuals because yes, Harvey Weinstein went to jail, but right now there are 50,000 other Harvey Weinstein’s being cultivated all across this country.

SA: You’ve spoken about how Black women, native women, and disabled folk, all deal with sexual violence differently and how we need to disaggregate those communities and talk about them differently. The same is true when looking at voter suppression. In both of these conversations, what do you think people are missing?

TB: I think people are missing what impacts those communities. So for instance, indigenous communities and black communities are the perfect examples. People don’t understand sovereignty and the issues around sovereignty in this community, because we act like native people don’t exist. You know, they’re a very small part of the population in this community, but they exist. Indigenous erasure–it’s criminal what happens to native folks in this country. Black people have a lot of visibility and are connected to pop culture and what we contribute in that way, but people don’t understand the material lives of black people in this country. They’re not invested in the material lives of black people in this country. So what we have is a lot of people who cry allyship, but they’re invested in their allyship as far as it can extend to their own guilt. They want to assuage their own guilt, but they’re really not invested in black humanity. It only can go as far as how good or bad you feel. Once that’s over and you feel you assuaged your own guilt, your investment is over. That’s why we don’t get very far. Yes, you change your profile picture from that black box and it’s over. What I think people are missing is an investment in our humanity. There is a way in which people don’t invest or go past understanding the material lives of marginalized folks in this country. Part of that is because they really only look at the tragedy. Our humanity is deeper than our tragedy. It’s deeper than our trauma.

My next project is about grace, and one of the things I’m examining is why can’t people understand Black rage. You don’t have grace for our rage, at all. When George Floyd got murdered and you saw people saying, “don’t destroy your neighborhoods”, and “don’t get angry, don’t vandalize.” I said, “No, we have a right to this rage.” Where’s the grace for us? If you understood black humanity, you would understand it. We have a right to a moment of rage for this country, and the fact that we are not raging every day is our grace for you. That’s an understanding of black humanity.

That’s the other part–the people who have power and privilege are also folks who are allies. And they may want to do good and they may say, ‘I’m an ally, I know I have a lot of power and privilege. I want to do good.’ But you still push us to the margins, because you will not turn over that power and privilege if it means that you have to be out here in the margins with us.

We all have some modicum of power, some privilege, and it takes a lot to decide to give that up. My child is queer, and I had to really do a lot of self-examination when I realized that my investment in the community and particularly trans folks and gender-queer folks were a lot of lip service until my child came out and said, “this is how I identify”, and then I was 100% invested in the livelihood and the life of people who identified that way because I knew my child’s life was connected to that. Before that, I just made sure that I used the right pronouns, I made sure that I had representation on my little panels. I checked the boxes. But I certainly was not invested in a very real way. I wasn’t putting my life on the line. I wasn’t standing up, I wasn’t vocalizing, I wasn’t showing up for that community in the ways that I do now because [of] my child. And I’m complicit in that. I had to examine myself in those years before my own child was. So I do get how we hedge our bets before we have a real investment. So I’m not 100% condemning folks in that way. I get the human instinct to not 100% turn yourself over to another thing, but I need people to be honest.

SA: How do you talk to people who don’t have that personal experience in the black community, or the indigenous community, or are not survivors? What do you say to them to get them to come on board when they don’t have that personal connection?

TB: I say be honest. I don’t try to shut people down, but you have to be honest and have some integrity and then we can work. People need to be honest about where they are. But don’t come to me as if you are “King Ally”–I’m here, and I’ve done the work, and I know. No–we are all doing the work. I am a learning ally. I’m an ally and an accomplice for LGBTQIA+ folks and always learning.

SA: People will look at the #MeToo movement or the climate movement and they often try and measure them by one specific outcome or a series of results that were impossible to have, ever. Then they will claim, ‘Oh, this movement failed.’ I hear this criticism a lot. What are your thoughts?

TB: I’ve been reframing this around this fifth anniversary a lot. And I think it’s absolutely dangerous. It’s about the visibility of survivors. It’s about the fact that people feel comfortable saying, “I am a survivor. I said, ‘Me too.’” It’s about people writing it online, telling their stories out loud. It’s two-fold. If you can’t understand what it is to hold this thing, then you won’t understand what it is to say it out loud. So once you understand what it is to hold the trauma, then you get the magnitude of being able to vote. That is the win. The win is in people being seen and heard and believed and finding community with each other. That’s not measurable.

Midterm Election Day is November 8th!

If you’d like to vote in person for this election, make sure you’re registered and plan ahead so you have the time to go and vote!

Have you reminded your friends? Bring them with you!

Find your polling place, see what’s on your ballot, check your registration, and more at Vote.org!

[The t-shirts worn in this latest series of V IS FOR VOTE have been designed by Katharine Hamnett. A portion of sales from each shirt sold helps directly benefit the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). For more information, visit WeAreTheFutureSDGS.com.]

Discover More