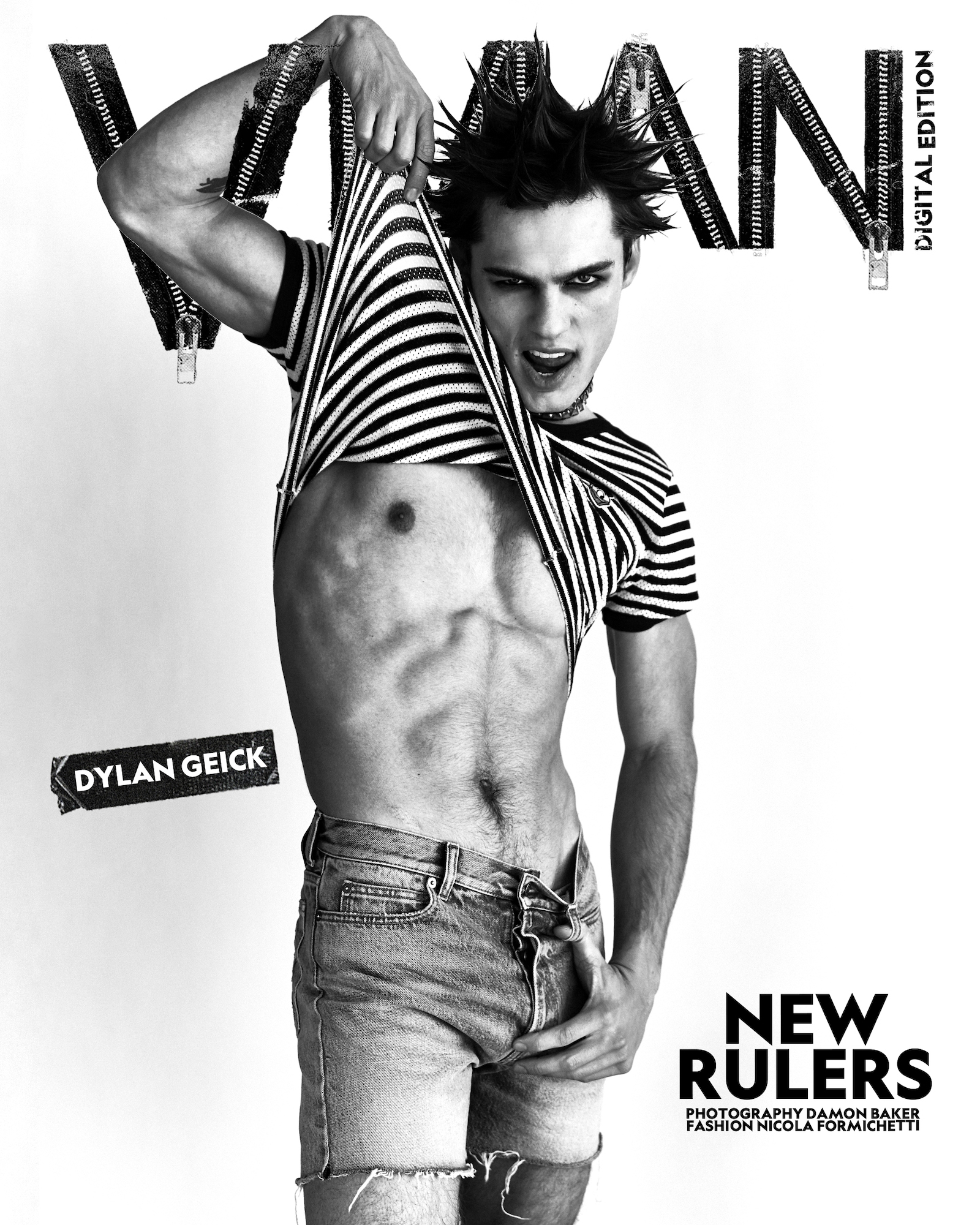

NEW RULERS: DYLAN GEICK

In an exclusive interview, Geick speaks about leaving the influencer lifestyle to join the army and the upcoming release of his second book.

This feature appears in VMAN 46, now available to order.

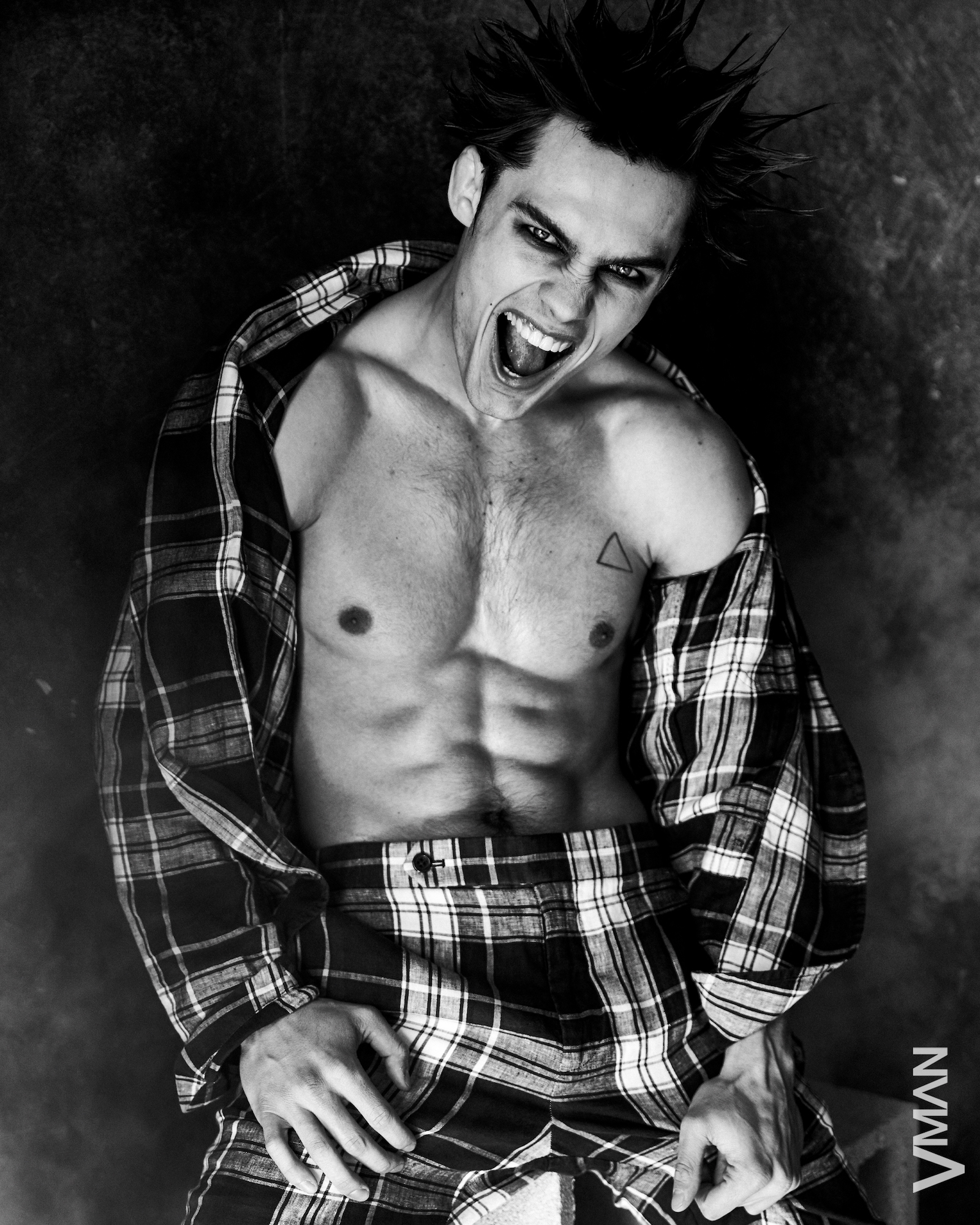

When you think of Dylan Geick, a few things come to mind: social influencer, for sure; wrestler, of course; and writer, most definitely. But one would be remiss and undeniably stupid to attempt to confine him to labels.

Humans are a highly complex species, which, due to societal norms, can be susceptible to apply categorical filters in order to give meaning, identity or value in the imaginary social media-based caste system we live in. Despite Instagram’s best efforts to regulate this by concealing the number of likes– the world values people based on social numbers.

Geick, however, is a special case despite his 678K followers on Instagram, over 200K subscribers on YouTube, and nearly 50K on TikTok. He often speaks out about the damage of social media and its ability to simplify people, ideas, and things that just have no business being simplified. He is a perfect enigma of contradictions where femininity and masculinity sing harmoniously, logic reasons with art, and war births tenderness. He is an embodiment of clashing complexities navigated by an enlightened consciousness that most of modern society will never come to terms with. Hailing from Chicago to the wrestling mats of Columbia University, and jet setting as a Los Angeles influencer to sleeping in unkempt army barracks while writing his latest works in poetry; Dylan Geick is many of things, but he absolutely cannot be simplified.

Read on in the exclusive interview with VMAN below:

VMAN: I literally just got done watching your YouTube vlog about your last day in the army. Why am I getting emotional? When your friends are hugging like, “this is my brother” and he starts crying. I started choking up.

DYLAN GEICK: I had a crazy 2020. I went from living in Los Angeles as an influencer. And then I spent basically a year in special operations training, doing crazy stuff, all during COVID. I didn’t see my parents for about eight months. I discovered COVID in basic training and knew nothing about it. It was an interesting time.

VM: It speaks to also how society thinks men are supposed to be strong with suppressed emotions. That was awesome to see the vulnerable expression because when you think of the army, you think fearless, you think zero emotion.

DG: And guess what, the truth is every guy in that video is a fucking warrior and is fearless, they are. And that’s why they’re okay with crying in each other’s arms. They’re drunk, but at the same time, no one’s embarrassed by that. No one. Everyone knows exactly what they’re feeling if they’ve been through it. And if you don’t, I think you’d get that it’s powerful. And the truth of this myth of the Western, strong male who doesn’t feel, it doesn’t map to reality for me. My influence is largely Western, I try to be global. I didn’t read the Quran till I joined the military and decided to figure out what this is about. And “The Odyssey” is referenced in half of my poems, and that poem is about this cunning, courageous warrior who’s trying to get home to his wife and he’s crying and he’s burying himself in the sand, and he gets home and he hugs his wife, and he’s being washed up on the shore and cleansed, that’s the language that they use. So I don’t think so. Every great hero is also a great lover in the history of the world. And that’s what I aspire to be. And I think most of those guys are.

VM: You’re a writer, you’re a wrestler and you went to Columbia for a bit. How did this all transpire?

DG: When people ask me what I do, I always say writer, I’ve always said that. I self-published Early Works frantically, as soon as I discovered that poetry was a real thing. And since then, I think that I’ve always just lived by this sort of Hemingway [philosophy]– if you want to get better at writing, you can read and write, but you also gotta live. Columbia was new to me for the year I went there. I don’t come from a lot of money, so that was a whole new environment and experience. Even just New York City was new, just discovering myself and my sexuality. I wrestled at Columbia and because I was not straight, I guess that piqued people’s attention. So I had this audience as I was discovering all this stuff. And then I chased that stuff all the way out to Los Angeles and I started working as sort of like a YouTuber and influencer. And then from there, I guess I wasn’t fulfilled enough and I joined the military. It’s been a crazy few years, to be honest.

VM: What was your intention in joining the military from Los Angeles?

DG: I just needed to do something else. And I tried going back to school, but I didn’t feel really creative there, I felt very trapped. I really liked Columbia and that it brings a lot of really cool minds together–I’ve met amazing people there, but it does tend to feel like a school with certain paths, whether that be in journalism, finance or engineering. And I didn’t feel like, creatively, I was able to be expressive there. Of course, the military is not known for that either really. (laughs) But it was a new experience and my motivation for the military was my stepfather, who raised me. He was a former army ranger, airborne sniper team leader in a real “high-speed unit,” stationed in Hawaii. That had always been something that interested me growing up, I grew up doing combat sports too. There’s a lot of tie-in between wrestling and sort of that blue-collar environment, like firefighters, police officers, and the military. I was looking for a way to push myself and try something new. And I think that that’s just where I landed.

VM: When watching that YouTube video, there was the guy who punched the ceiling and denied it with bloody knuckles…

DG: Yeah, I still don’t know if he punched the ceiling. He very well could have punched someone else, there was a lot of people punching people.

VM: This is true, but he called someone a derogatory gay term and you looked at him and you said, “What do you mean? I’m gay.” And he responds, “Well, I’m gay too, so.” Was he?

DG: Probably not. But you know what’s crazy… if he were, it still wouldn’t surprise me that he talked that way, because that’s the language that we use in the military, I’m guilty of it too. It’s almost like the military is still lagging about 10-15 years behind in social graces. And it’s something that the military is working on. But also, when you’re in super high-stress environments, that one was specifically leaving selection for a really high-tier special operations unit. And it’s just a bunch of guys, it gets very frat house-y. That’s one of the things that turned me away from the military. You don’t want to be the guy who’s always on a high horse, but I do try to correct where I see stuff like that. But the other thing is, I don’t think that guy was homophobic. I don’t think he would ever have treated me differently necessarily if I was gay. I fit in well and I understood that culture because it’s sort of the same as wrestling where they respect you for your skills. If you go out on the mat or out in the field and you do your job and you’re good at what you do, they don’t really care who you are. You could be black, white, Muslim, gay, straight, it doesn’t really matter. They might clown you for it, we all clown each other for everything, because that’s just how brothers are, especially brothers in the army. But I don’t think that there’s any sort of hatred culture or anything like that in the army, but you definitely run into that stuff.

VM: What is it even like for an openly gay or queer male in this scenario?

DG: If I’m being honest, I think everyone is going to develop a skin there. It doesn’t feel good to hear someone call gay or something similar. But at the same time, you’re in an environment where people are getting in your face, they’re yelling at you, you get shoved, push-ups. You start to take it easy on other people. Honestly, I’m bisexual, but I wasn’t even the only openly gay person, even in my 200-person basic training unit, there were probably three or four people.

VM: Do you find solace or community knowing that there were others like you that were open about it? Was it less hard to deal with?

DG: I think, yes. But I was already so used to it with wrestling where I literally was like sort of the first or second guy ever to be out. So if there was no one there, I just think it would have been business as usual, I’ll just show them what I’m made of. But having other people there made it really easy.

VM: Are you currently in the military now or are you through?

DG: I’m on my way out, but I’m in literally for a few more weeks.

VM: Wow. So then, what’s next?

DG: The book has been what has been my focus for, honestly, the entire year. As I’ve gone through training, I’ve been writing non-stop, just paper and pen, my red headlamp, in the bunk beds, written in the field and the woods, wherever. We always had to have a pen and paper on us. And I smuggled books in. What’s gone into making the book is pretty incredible to look back on. I was just really feeling beat up in training, trying to keep a relationship alive, and stay in touch with my friends over letters. And then COVID hits, so mail stopped for a few weeks. And all the while, through all this stuff, I was writing poetry and really looking inward and analyzing the military experience. It’s like a boy discovering the influence of the empire and at the same time just trying to hold together a long-distance relationship over letters every night. I think it’s a really unique reading experience. I think it’s really matured from my last work. My early work is super nascent and I knew that when I wrote it, and that’s why it’s titled Early Works. But if that’s coming of age, finding myself, this is like finding the world. The working title is I Have Been Bleeding, which is [an ode to] Hemingway’s: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” As I’ve been going through the last year and a half, I’ve just been trying to be as truthful and honest as possible as an artist and just write it all down. It’s a full collection, some of them are pretty lengthy at like 40-50 pages.

VM: Is there any sort of overarching topic or theme that you’ve been going through?

DG: It’s interesting. One of my friends who’s a poet that helped me edit the manuscript was like, “There’s so much about your relationship and love in here.” But my sister, who’s super into mindfulness and meditation, said “Wow, you have a lot of stuff about meditation, being present, being mindful, being reflective in this book,” that’s what she picked up on. And then when my military buddies read it, they said, “Gosh, this is so raw to the experience of being in the field or on a (inaudible).” So I think people will probably extract different things from it, I hope. But it’s definitely a book about love, but it’s also definitely about hardship, expanding my perspective, becoming really global in my perspective.

VM: I feel like people love to categorize other people. One might think of wrestling, you think of the army, but you necessarily think of poetry. It’s wild how these all are a part of one person.

DG: You’re absolutely right, in a modern age. However, writers have been warriors for a long time. And I do think that those two arts are linked. There’s a long tradition of it, like in Japan with the Samurai. You have warrior monks and the templars. I think there is a tradition. And I’ve been connected to this little community of like veterans and, specifically special operations, higher-tier caliber men, guys who go to Columbia after, there’s a big veteran community at Columbia. Guys like that are interested in telling their experiences. And that’s something I don’t do. I have not been deployed, I’ve not been in combat. But there’s some incredible perspectives by men who have served and been in combat and lost people and experienced traumatic and also beautiful things. And they write about it, and some of them are really skilled.

VM: What are you taking away from your time in the army?

DG: I’m appreciative and I’m humble more than I’ve ever been. Just things like a bed, for example. I’ve slept in the woods, in the rain, in a wet bag. My first time sleeping on the field I was using a bag of water, a Camelback, as a pillow. And I woke up and it was ice. So I’m a little more appreciative. I was pretty spoiled as an influencer in Los Angeles, flying around all the time, and now, I’ve gotten to meet people whose first plane was the plane they took to basic training. I came into contact with poverty that I had never experienced or heard of. I had a friend from Tennessee who said, “Yeah, it’s pretty common to have an outhouse,” this isn’t a myth in America. Being from Chicago, living in New York City, living in LA, you don’t meet those people, you don’t get those perspectives a lot. So when I say “expand my perspective,” I mean totally, radically changed.

I think my goal is to just be really artistic. I don’t want to go back and worry about money and get on TikTok and start doing that stuff. Not that I don’t respect that, but I want to be chasing a more artistic calling. And maybe there’s a way to do that with TikTok, I don’t really know. I’ll explore that space, I’m happy to be digital and plugged in. I think if Van Gogh was on Instagram, his feed would be a trip. I don’t think he would think he’s too cool for Instagram, he would be posting crazy selfies with crazy filters. Da Vinci might be a little snobby about it. There are certain things that cheapen you as an artist and as a brand, but there are also just ways to be online and be present. So whatever that looks like, I don’t know. As a writer, I’m not a big fan of Instagram poetry, I think you should be able to own your art and sell it. But we’ll see how it takes shape, as a writer of the 21st century.

VM: Let’s talk about the world of TikTok. I see you also play the piano… is that something that you want to explore in the future?

DG: Music, definitely. And TikTok, I do think can be a great platform for that. You’ve seen how it’s literally just shaped music charts for the last year, made people a lot of money if their song is trendy to dance. I do think it’s a great platform for music discovery and artistic experimentation of freedom, honestly. So I probably will be on it and I probably will be exploring music more when I get out.

VM: What do you think is the plan for you? You got the book, you want to dabble in music. Five years from now, what do you think your life’s gonna look like? And, you know, hopefully, we won’t have a COVID world, but in your ideal scenario, what would that encompass?

DG: So as long as we’re not in another pandemic, I’d say, I don’t like planning. I hope five years from now, I feel like I’d like to be moving around in Europe, probably still writing, probably getting into that cafe scene there. I haven’t spent much time in Europe. But I’d love to backpack through, see what there is to see. That seems like a five-year goal. But music, writing, those will probably stay at the forefront. I’m not out here looking to build a TikTok empire, or a brand, a makeup line, really not out here to make that much money. I just want to do the things that interest me and survive while I do it.

VM: It seems like you have a bit of a love-hate relationship with L.A. Do you?

DG: (laughs) Yeah, it’s true. With social media, I think L.A. for me has been this extension because it’s so focused there. People are always like “Oh, people are leaving L.A.,” and I’m like…are they though? Okay, Jake [Paul] left and Logan’s leaving. We’ll see what happens, we’ll see if there’s a diaspora of influencers across the nation. L.A. has been the locus, and it represents a lot of things. Have you seen “The Social Dilemma?”

VM: You know what, I have not.

DG: I’ve listened to a couple of podcasts with him when I was in LA, and I grew really concerned with the ethics behind what I was doing. Am I making myself some sort of idol or icon? And am I contributing to this addiction to social media, to people having their privacy eaten? And can I do that as an artist, if that’s how I’m able to monetize in the 21st century, or as a human with a brand, making silly videos. I didn’t really want to contribute to that. So I had a lot of problems with the economics of it. Then on top of that, there’s a lot of fake stuff in L.A. People just want to hang out and take photos to grow their numbers, and that’s the last thing that I’m interested in. It was really hard to find genuine people. And I did find people like Damon Baker and Matthieu Lange, who’s a young director, just really cool people. So it’s a love-hate. You get those artists and those creators and free spirits. And you also get people taking advantage of it, math people, algorithms, and I don’t like all that.

VM: It’s rare that you speak to someone who’s able to differentiate from the soul and public connection or like how we see your soul through the lens of social media.

DG: Especially when Instagram is almost like a business card now, and it’s some sort of measuring tool. But for what? What number’s above my name? It’s just so silly and vapid. And I also realized that like anything in life, it’s just luck, it doesn’t mean anything. But then the consequences are real, because I also know a lot of 20-year-olds who are worth seven and eight figures. So if that’s your goal, it’s a real opportunity.

VM: Looking back at how your life has evolved and the things that you’ve come to terms with, as far as the internet sensation versus reality and your own soul’s path. What advice do you have for people like you who are artists, but who also feel it’s necessary to have a substantial platform and are kind of selling their soul?

DG: I think that they are, and I think that hits it on the head. Across my Instagram, I have what I call these little moments, where I post the craziest shit, with these long rants. And I get a few dozen comments of “I love this” and “This is why I follow you.” But most people are like “God, get off your pedestal.” But I can’t help it. And the fame of the 21st century is pocketed.

It’s like you’re a liquid in a mold of these algorithms. What do they want to see? I guarantee you, if tomorrow the Instagram algorithm stopped prioritizing pornographic things that capitalize on outrage or lust and it changed the algorithm models to whatever makes people think the hardest and that’s going to get the most likes, everyone would change. I would like to get to a point where no matter what that algorithm looks like, my content is the same. And I’m saying what I want to say, and I’m not worried about, “Well, I could say the same thing, but also take off my shirt and then I’d get 50,000 more likes and make more money.” That’s a powerful pull. You get more attention and more money, which everyone seems to want.

My advice is when you go in, know that there’s going to be a mold that that system is looking for you to settle into. And once you do, it’s really hard to change because if you’ve always posted one type of content and you’ve really set into that mold and you start posting this other stuff, the feed will hide it. It’s not even a great way to express yourself because you don’t know what people are seeing and what they’re not on an individual basis. Don’t take it too seriously and just be true to whatever it is that you want to say. You have to find your own voice without being influenced by how to tell it. A perfect example of this is with Instagram poetry, and I’d said I’m not a huge fan of Instagram. Well, look what Instagram has done. It’s shortened poetry. You see these huge poets like Nikita Gill, even Rupi Kaur, who’s a 21st-century poet I like in certain ways. But Instagram has changed poetry to where it’s short form, it’s one stanza. The lines are short. Why? Because someone’s scrolling through a feed. Even if I like this person, I’ll read their novel later. But if they roll through and it’s a six-line stanza, okay, I can get through that. Not that you can’t say something with six lines, but you could probably say more with a little bit more freedom. And I just don’t want to feel restricted. I think what Instagram does to poetry it does to all things, which is it puts it in these molds that I’m not interested in fitting in. So my advice would be: Don’t even try to fit in and just forge ahead.

Discover More