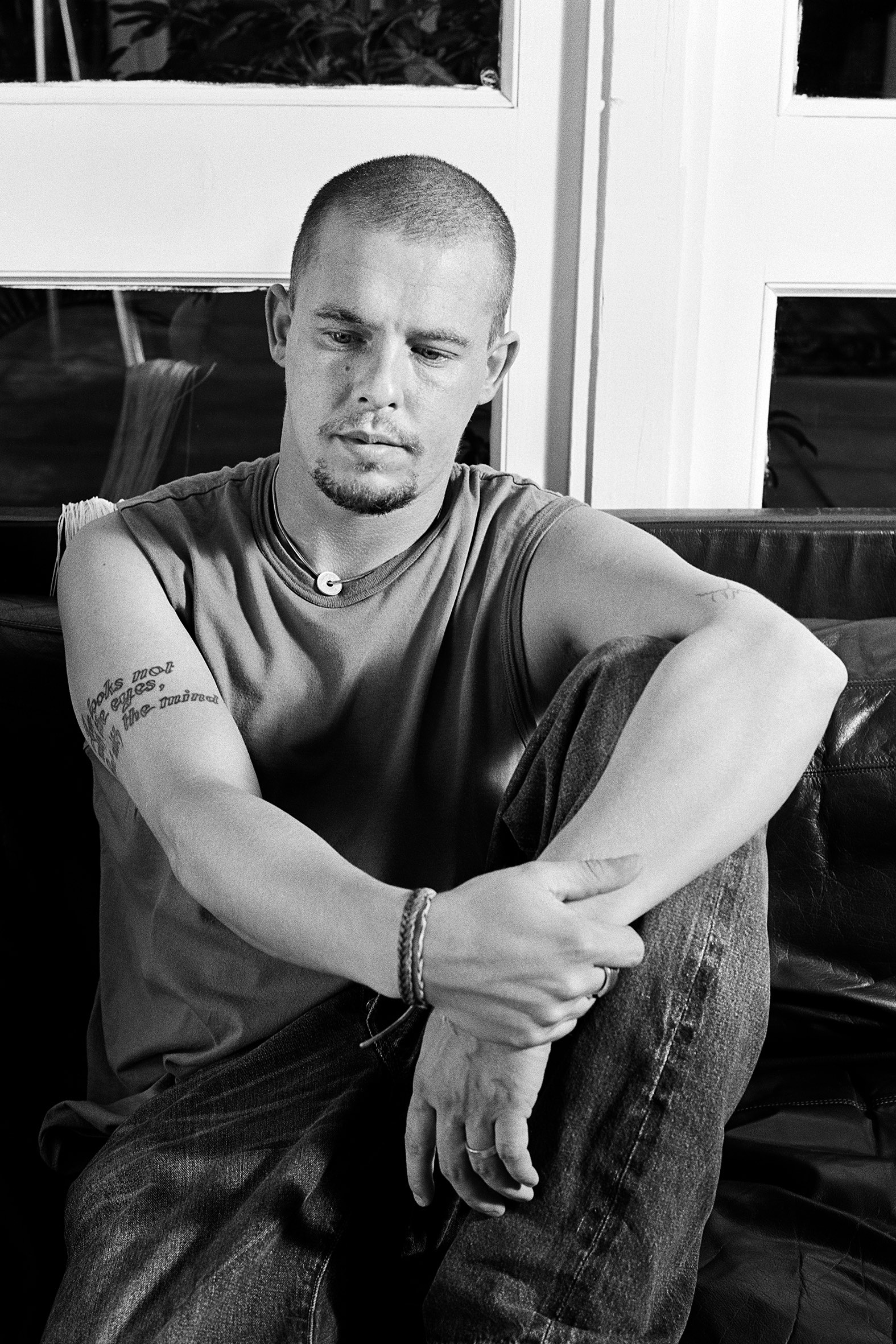

Photographer Ann Ray on Her Friendship with Alexander Mcqueen

Photographer Ann Ray reflects on her thirteen year friendship with legendary fashion designer Lee McQueen

Better known to fashion as L’enfant terrible, Lee Alexander McQueen’s legacy is one of rebellion in applying his twisted genius to iconic designs. He tailored clothes cutting them on the body, cursed, showed crude displays of derriere on the runway, and managed to piss off the fashion world entirely. But McQueen wasn’t following anyone else’s rules, he was rewriting them himself. Arriving on the 10 year anniversary of his death, longtime friend, collaborator, and photographer Ann Ray is sharing a glimpse at her time with McQueen in a new exhibit opened by Barrett Barrera Projects in St. Louis. The exhibit follows an intimate look at McQueen’s design process and backstage at his famed runway shows. Moreover, the exhibit commemorates the unique friendship Ray and McQueen shared. V got the chance to sit down with Ray to discuss her projects, the exhibit, and her friendship with the late designer.

When did you first meet Lee Alexander McQueen? How would you describe this encounter?

I met Lee McQueen at the end of 1996 in Paris at Givenchy. I was asked to photograph him for two weeks during the creation of his first couture collection. We were both very reserved, so it was a kind of mutual observation—what shy people do. We didn’t talk much, but the connection was intense. We worked as much as we laughed, that time—January 1997—was a blast.

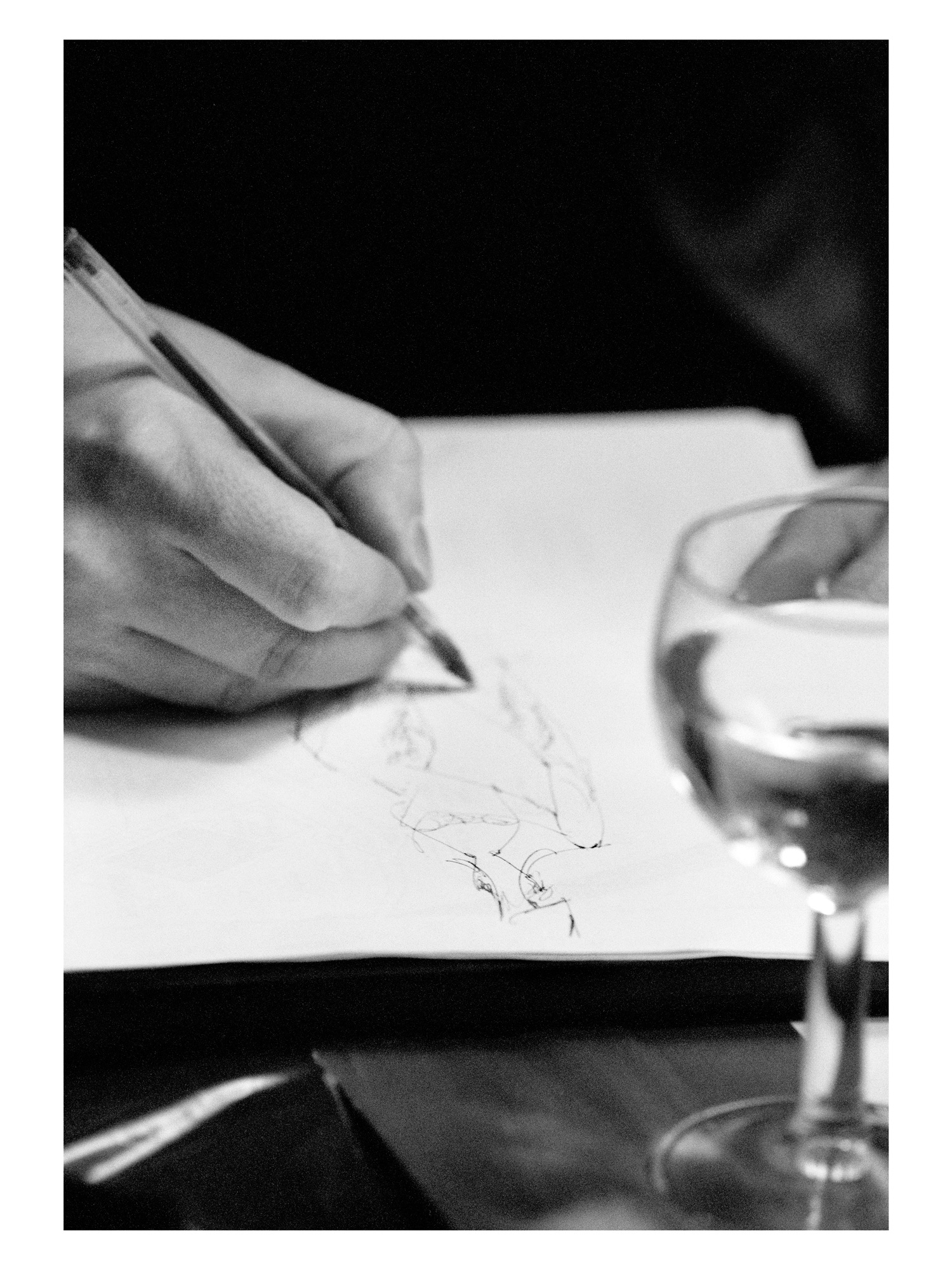

I precisely remember observing Lee create a dress as a volume in space from a roll of fabric in 30 minutes or so. It was astonishing. I was observing, absorbing, and Lee watched me observing. I remember with the same accuracy the night before the show, in the atelier, when Lee asked me what I thought of his work…tough question. It was already about truth. It seemed obvious though that the only possible way between us was radical honesty. So, I told him honestly what I loved in his collection, and what I liked a little less, and why. “You’re right, I failed, it’s crap,” was his answer. I denied and nuanced his words and reassured him the best I could. He was hearing much more the critics (even carefully formulated) than the compliments. Already in search of excellence, by all means.

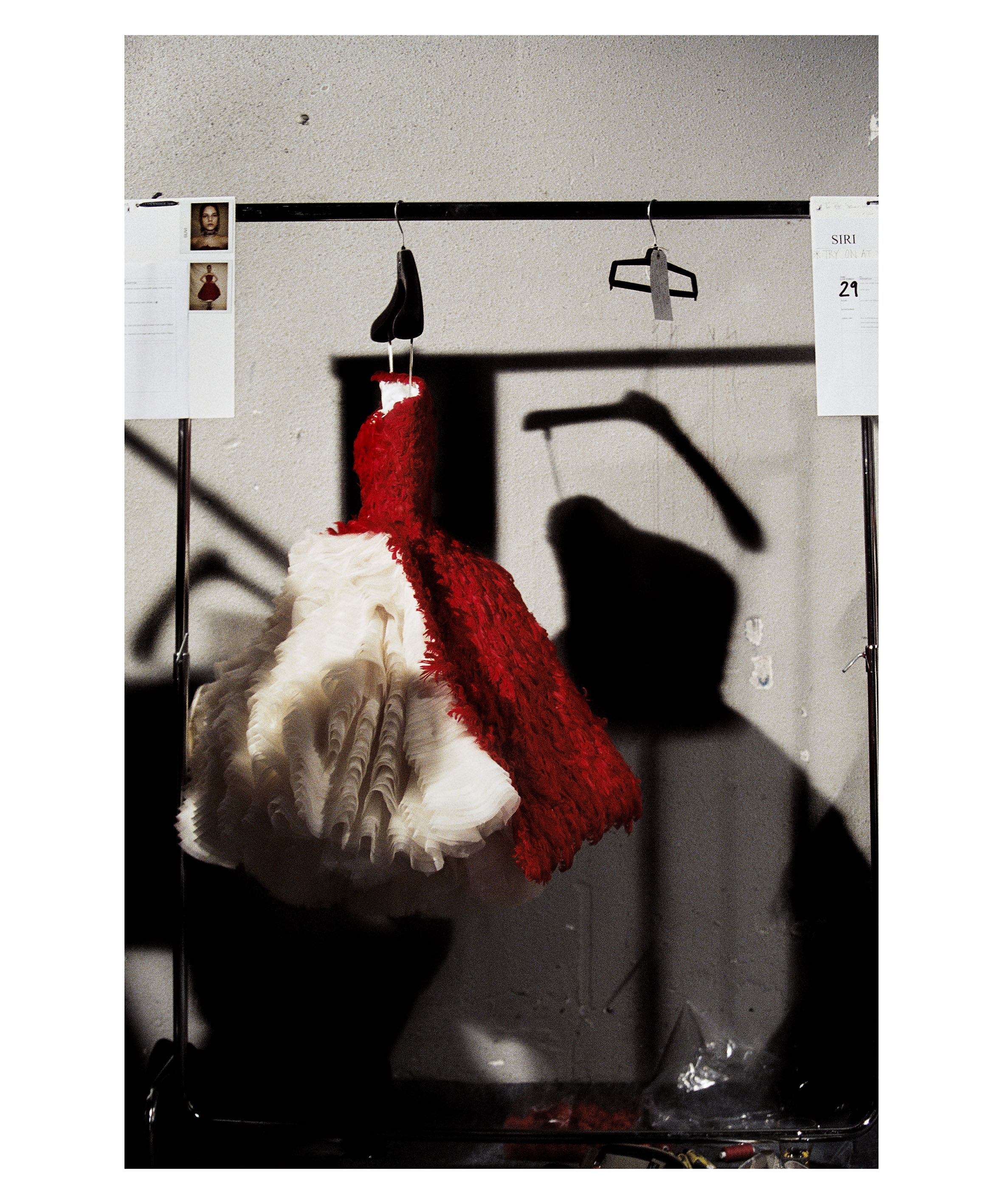

In the following years, Lee would often take time with me on the day of the performance to show me the garments, one by one, describing his intention, a pattern, a new technique, or a detail. These moments together were pure bliss. A revelation, each and every time. What a joy too.

Then he came to Tokyo in April 1997 for a few weeks, presenting his first pret-a-porter collection, giving interviews, discovering Japan and the city, etc… I was living there at this time. Once again, we spent long days together and it reinforced the link.

What was the first impression, initial thoughts after meeting McQueen?

I felt that he was an incredibly talented person, a visionaire, hard-working, very funny when happy, shy, sensitive, and kind. A big-hearted man.

How and when did you start photographing him? Was it your idea or Lee asked you to do it?

I moved to London during summer 1997, and the first people I met on my arrival was the McQueen team, in the Rivington Street studio at this time. Lee had no money, so the deal was settled in a very simple way: “I love your photos. Give me photos, and I will give you clothes.” It never changed afterward. It was all about freedom, and trust.

What was the goal for taking these photographs, initially? What were you and Lee planning to do with them?

I never thought of documenting Lee’s life. I was in presence of something raw, sincere, overwhelming: himself, and his creations. As an artist myself, my photographs were my answers to what was delivered by Lee, in front of my eyes. Like a silent conversation. I want to believe he liked what he found in my images, like an echo maybe, otherwise I don’t think it would have lasted so long. It just happened, it started, and never stopped. I loved him and felt the necessity to put into images, as symbolic as possible, what was happening in front of me. Many people were talking about fashion, whereas for me it was something else. Far beyond. I was in search of the naked truth, his truth, and mine probably, through interstitial moments, who may reflect the ephemeral Beauty of what was visible for a few moments. Of what it inspired to me. It had nothing to do with fashion, it was more like putting silent screams, hopes, dreams, nightmares into photographs that would last. Analog photography is very tangible, and it’s a craft in itself. So, it was an obvious choice, natural in the late 90s, more special in the XXIst century.

Very few images were used by the press, or for invitation cards, or special projects. I would say, five to 10 a year. Lee and I never talked about doing something special with the photographs until 2007, 10 years after it began. As if we both knew that we were doing something major, that would take shape in due time, anyway. Thus, we took our time. Sometimes we would look at the contact-sheets together, that’s why I know some of his favorite pictures. We talked more precisely of how and when we would create a book together in early 2009, Lee was supposed to come to my house in Paris for this. He was over-excited about it; I remember his joy. It’s a tough memory, another unfinished dream. It is during this conversation in 2009 that he said, “You have my life in pictures.” I became aware of my role at that very precise moment: a responsibility, a duty. However, to be honest, he probably knew very early, long before myself, what was the intention. The plan. Lee knew what he was doing. Whereas for me, as vertiginous as it may seem, it was just an immediate necessity, a sum of essential rendezvous that occurred very naturally in my life and that seemed to have no end. I was in the instant, not in any kind of projection. The present was too intense to be disdained or formatted in any kind of long-term project. I lived every one of these moments out of my zone of comfort: over-exposed. Until the next one.

How did your relationship change, if it did, while you were working on these photographs?

I never felt any changes in the essence of our relationship, based on trust and mutual care. The London years, when I lived there from 1997 to 2000, were very special and tender since we would meet very often. For work and private moments. As far as photography is concerned, I would pop in the studio, be there for each show, and every time a magazine would ask for a portrait, I was in charge. Feeling honored and happy about this. So, I did many portraits of Lee during these four years. We were both sad, I guess, when I left London for Paris. Strangely enough, it coincided with the McQueen shows making their debut in Paris. Then I kept performing my duty, focused and devoted, being only vaguely aware of the success and fame and noise around him. At the beginning of this century, I was spending very little time in fashion, putting most of my time and energy on personal projects including numerous artists, of all kinds: musicians, conductors, choreographers, dancers… Lee was my special bond, my special secret story, oblivious of all the frantic atmosphere that I could perceive but ignored. I must say, it was a very calm feeling. I had to be there for him, that’s all. I realized the obsessive madness about Lee when he died. All these strangers suddenly writing “RIP Lee” on so-called “social media”, that was very awkward. Or inappropriate. No matter how much you admire an artist, death requires decency. Well, in my world.

That’s probably when I understood that the legend and the man I knew and loved would never reconcile. I still embrace this idea today. My photographs deal with Lee McQueen, the man and the artist I had the privilege to know. In other words: the truth of the legend.

The less people talk about Lee, the better. Images speak for themselves. Images don’t lie.

Could you see yourself continuing this project if McQueen wouldn’t have passed away?

That’s a good question. Almost philosophical.

Part of the answer consisted in working for Sarah Burton many times after Lee’s death in 2010, until 2017. Simply because McQueen is like a house, or a family. It didn’t make sense to stop at the date of the founder’s death. It would have been disrespectful of the devotion of his team in general, and of Sarah in particular. We arrived at the same time in the family, in 1996. It’s not a detail.

The rest of the answer has been given in my publications and exhibitions since 2010. If I look at my photographic corpus—this heavy 35,000 analog photographs archive about Lee McQueen as a global artwork, it has to be transmitted in a consistent way. With the idea of duty, and of the truth of images. I devoted a lot of my time on this transmission since 2010, the climax being the exhibition in the photography Festival of Arles in 2018, “Les Inachevés”—“the unfinished”—with 169 photographs exhibited over a 500sqm space, and the publication with the same title. I have been as far as possible in building this exhibition and this book, like a vibrant homage to the man and the artist, Lee McQueen. I recalled all my memories to stick to the naked truth, without any compromise. You don’t escape unharmed from such a journey. I did the book in the same vein, with an absolute free spirit, thanks to my producer Myriam Blundell, guided by the obsessive thought that I had to present the truth through the art of photography and a few texts carefully are chosen, and the truth only. Lee’s truth, through my prism. The legend being what it is, about Lee McQueen, I constantly came back to the essence of the work, and the man’s spirit. It’s been a demanding exercise; however, nobody could do it in my place. That’s where the word “duty” takes its full meaning.

Now, the question remains philosophical because everything has to come to an end. Arles’ exhibition and book embodied certainly a closure.

I am keen to transmit again Lee McQueen’s work and life in the upcoming years, through my photographs and close memories, however, I have to make choices. That’s why when Susan Barrett and her team came with their idea of “Rendez-vous,” a new exhibition exploring friendship and art around Lee and me, that was a wonderful idea to extend the transmission, after Arles.

As a matter of fact, the photographic material is so rich that I can reveal endlessly new images of Lee McQueen. It creates novelty in continuity. It’s endless. Maybe that’s what I was looking for in the first place when doing this work for 13 years finding a way to engrave Lee’s life through raw or ethereal images, like fragments of eternity.

Why present these photographs in St. Louis? Is there any significance to the venue that you chose?

Susan Barrett was the first one to exhibit my McQueen photographs in 2013 in Saint-Louis. It felt right to work again with her, especially as this project is all about friendships and interactions between people who create things together. We wanted to make something happen together again!

We agreed very quickly with Susan and Jessica (the curator) on the main theme and the title “Rendez-Vous.” Then it seemed interesting to exhibit some garments as well from Barrett Barrera Projects’ private collection. Susan devotes so much of her time and energy in gathering this collection, it is meaningful to share it with the audience.

What are you planning to do with these photographs next? Are you going to show them elsewhere, outside of St. Louis?

We are working on it. I’d like as many people as possible to see my exhibitions, as a celebration of Lee McQueen. I hope they travel in the States and maybe beyond…

Could you see yourself pursuing another project like this sometime in the future?

Not really. First because working so closely with Lee, with all the consequences, has been a blessing and a curse. I don’t think I could do it with or for somebody else, and even if I could, I don’t want it. This belongs to another era in many ways: an era when you could be extremely creative in fashion (or in spite of, or against it), an era when the value of time and of process was very important, an era when I was happy to devote my art to another artist, especially if he was a tender friend.

I realized suddenly that none of us is immortal, and I now feel the relatively quiet emergency to present my own perception of humanity through other artworks, using photography and other media.

I say “relatively quiet” because I want to take time to create, to process my own experiences and visions, to interact with people that matter, and finally to learn from the time elapsed. There is an invisible logic in everything, like an inner rhythm. There is a timing, and a context, in your own creative cycles. I feel ready now to use my writings – unpublished whereas I have been writing for more than 25 years—as I feel ready to work on my first full-length movies – after many short-format movies made over the past 10 years. I believe in accidents and “beautiful mistakes” (the title of an upcoming exhibition, by the way), that’s why I need to handle the passage of events & time very carefully. Otherwise, you miss the accidents, these very human crack-ups, these interstitial moments, essential in all my creations. I need that appropriate rhythm, the one you discover over a lifetime and transform into your inner spiritual music. It gives me clarity to create.

So, the next five or 10 years will be devoted to more closures and more openings.

More closures with purely photography exhibitions. I still have a lot to share, including 3 major projects: the “Blind Faith” project, presented for the first time at Ca Pesaro Museum in Venice in April 2019; “What Eye See,” gathering my numerous works with dancers and choreographers since 2003, that will come out through an exhibition and a new book to be published in 2020; and “how I became a woman,” a very important project devoted to women.

More openings, that resonate as necessities: collages and calligrams, a creative documentary movie and a fiction movie, and the publication of poems and novels.

Festina Lente, indeed.