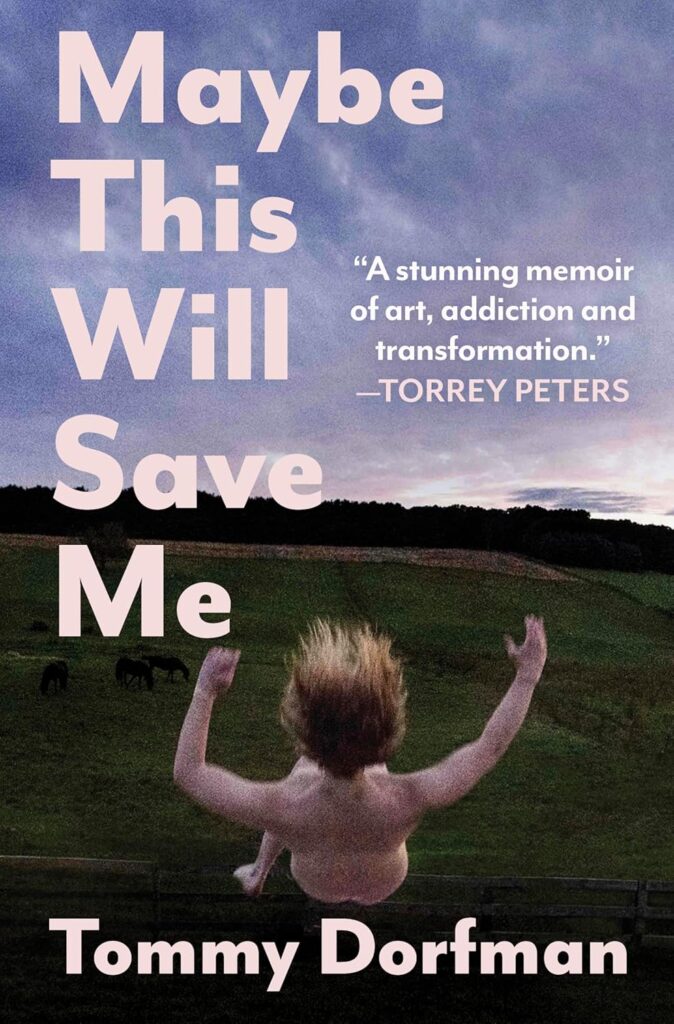

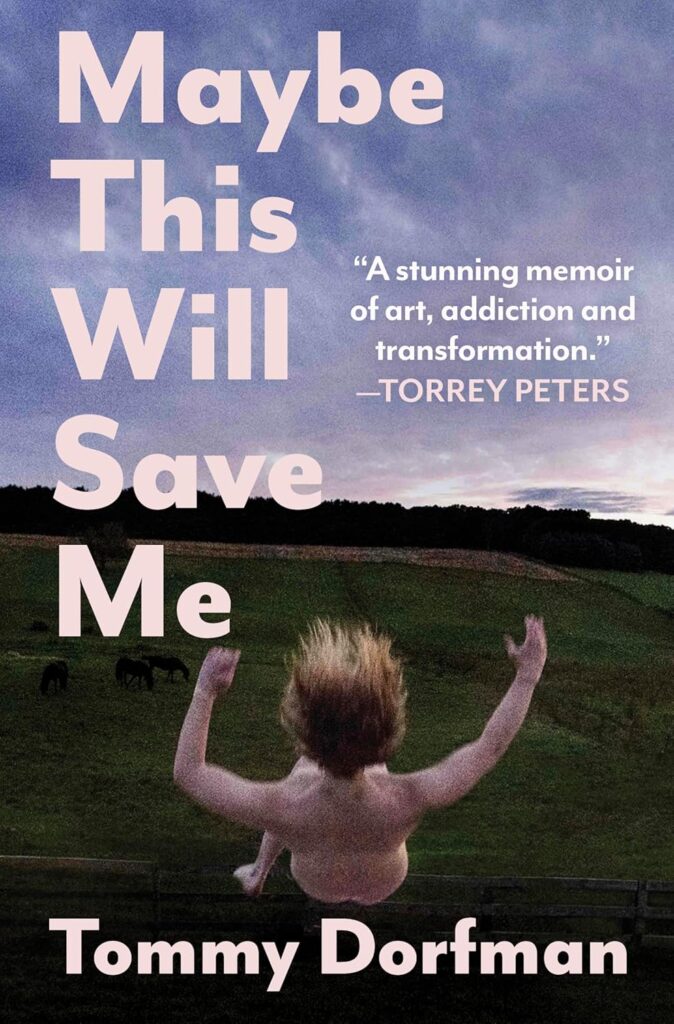

Tommy Dorfman has always been writing—essays, poems, screenplays—but Maybe This Will Save Me marks her first foray into published prose, a project four years in the making that defies conventional memoir. What began as a collection of essays gradually took shape into something more cohesive, more personal, and ultimately more revealing than she initially intended. In this conversation, Dorfman speaks with V about the emotional toll and creative freedom of writing the book, the decision to share intimate moments of her life, and how storytelling—whether on the page or screen—has always been her most honest form of expression.

Mathias Rosenzweig: How long did it take to write Maybe This Will Save Me?

Tommy Dorfman: Four years. Some parts were written earlier—essays and stories I reframed or reworked. I’ve always written. The impulse to create a collection of essays eventually turned into what’s being marketed as a memoir.

MR: It felt like a memoir.

TD: That wasn’t the intention at first. I wanted to publish essays. But the book took its own shape—it revealed itself in the process. I started writing in 2020 and finished editing in 2024.

MR: People don’t realize how long it takes. I’ve spoken with authors who are like, “I finished this two years ago, and I don’t even relate to it anymore.”

TD: Exactly. And a lot of life has happened since I turned in the first manuscript. Which is a good thing. More time means more perspective. The book focuses mostly on earlier parts of my life. Even what’s considered the “present day” spans 2020 to 2023. But I’ve wanted to do this since middle school.

MR: I was going to ask that. Because given the effort involved, I figured this wasn’t your first time writing.

TD: Not at all. I’ve been writing as long as I can remember. Not diaries—more essays, poems, blogs. I’ve also been professionally writing screenplays and still do. Writing prose felt daunting but exciting. I knew if I was going to do it, I’d do it myself, and take as long as I needed. I also knew I’d write more eventually. I tried to take pressure off this book, knowing there’d be more. I want to write fiction at some point. I like playing around in different disciplines.

MR: You really didn’t shy away from revealing intimate stuff—your thoughts, your body, relationships. I’m sure there’s more you didn’t include, maybe for another project. But were you constantly asking yourself, “Do I really want to share this?” It’s like when a pop star writes a diss track—someone’s going to hear it.

TD: Yeah. It’s like a three-minute diary. Or sometimes a whole album. But for me, I had no fear for around 90% of the book. It doesn’t even feel like me anymore—it’s different seasons of my life. And if you know me, I’m an oversharer. I’m an exhibitionist in some ways, but I don’t really present that publicly. I don’t know how to do it on social media. I’m not that kind of performer.

A lot of my screenwriting hasn’t been seen. My first film comes out this fall, and I’m directing another one—both based on IP. I’m too scared to put personal stuff into a movie the way some people do. I don’t have the Benny Drama complex of centering myself visually. But I did want to take control of my narrative with this book.

MR: And reading is such a uniquely intimate experience.

TD: Exactly. It gives space to interpret and imagine. You can’t multitask when you read. You just read. I find it uncomfortable to directly address a camera and be vulnerable. I don’t know how to do that. The book was the only way I knew how—maybe there’ll be others. I can do interviews, but even then, I slow down a lot. This was a chance to invite people into my experience as truthfully as I could. I don’t think art is worth making unless it challenges both the artist and the audience. I feel liberated when I’m writing. Some parts of this book are intentionally unedited—stream-of-consciousness—because when I tried to write more traditionally about addiction or my transition, it felt too self-protective.

There’s a whole Notes App section that’s literally just copy-pasted. Every time I tried to make it polished, it lost its truth. There was a section—text messages with my ex-husband—that I originally included word-for-word from iMessage, but I cut it. Without full context, it felt like it was just taking up space. I also wanted to be considerate—he and I are still close. There are people I excluded for similar reasons. And the ones I wrote about openly are usually people I don’t care to maintain relationships with.

MR: I think what matters most is how you feel about it. Like Joan Didion—it’s just documentation. You’ll look back in 10 or 20 years and say, “That’s where I was.”

TD: Totally. It’s not about how we feel forever—it’s how we felt at that moment. I often underestimate how much space I take up, or don’t. And sometimes the things I think are least interesting turn out to be the most compelling to others. I wanted the book to feel like me, but also like you didn’t need to know me to enjoy it. You could pick it up in a bookstore with no reference point and still connect with it.

MR: That really comes across. You barely mentioned your acting career. It wasn’t like “I was born, and then I made it, and here’s the rest.” You really zoomed in on unexpected moments. Even spending so much time describing your ancestors’ lives, not your own—it’s rare. And I think it makes the book feel bigger than just your public persona.

TD: Yeah, I just don’t think that stuff is all that interesting. I included it because it mattered to my personal growth—and because I know some people will be curious. Especially young queer people who see themselves in me. I had actors who helped me believe I could do this, and I want to return that. So I included just enough to offer a kind of reference point—not a toolkit, but a real account.

MR: And your writing about Hollywood didn’t come off as complaining—it felt like a rare window into the disorientation of sudden success.

TD: It’s like anything in life—not what you expect. It inflates your ego. Then you either do the work to deflate it, or you don’t. My relationship with fame is constantly evolving. But I still think the most interesting things to write about are addiction, recovery, and relationships.

MR: Do you think that’s because it gave you a new way to revisit those topics—not in therapy, not in conversation, but in this unique context?

TD: Definitely. I got to examine my adolescence from a deep, almost anthropological perspective. That kind of clarity wasn’t available to me at the time. Writing nonfiction requires distance. Even if you include old writing, you need a framework around it. It was cathartic—but also exhausting.

For example, I wrote an essay from my 14-year-old perspective about being raped at that age. Every time I tried as an adult, it felt wrong. So I did a deep meditation to get back to that younger version of myself. I finished the piece and didn’t write again for six months. That’s how intense it was.

MR: I felt that. There’s a moment in the book where I had to reread a passage like, “Wait, did that just happen?” The ambiguity mirrors how those experiences often unfold in real life—murky and disorienting.

TD: Yeah. Some pieces I could type out easily. Others I had to dictate while lying in a dark room. It was physically and emotionally draining. But it’s not dissimilar from how I write screenplays. Tarot helped too—it became a tool for grounding and clarity when I was blocked. Each card prompted a new direction.

I have tons of half-finished essays, and others I cut completely. Some were four sentences and a list of bullet points. I’d leave things, return later, move stuff around. I realized certain heavy sections needed to be spaced out—like the nominee collection. I wanted an engine to keep readers moving forward, with levity to break up the darkness. That was a big part of editing.

And I owe so much of that to my editor. We worked closely, and we didn’t always agree—but that made the book stronger.

MR: A little push and pull is good.

TD: Exactly. I didn’t want this to just be the version I wanted. I don’t think literature needs to be accessible, but for this book, I wanted it to be—to anyone who might need it.

Photo by Clips Split

Discover More