VNEWS: Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech”

Curator Antwaun Sargent and Director of the Brooklyn Museum Anne Pasternak discuss the newly unveiled exhibition celebrating the late great’s multidisciplinary work

This story appears in V137, available to order now

Like jolts of lightning, fads come and go. Though the work of a true creative, one intent on reshaping creative dialogues, weathers all storms. Naturally, the path-blazing legacy of the late great Virgil Abloh transcends all concepts of time. Now, nearly 8 months after Abloh’s passing, the creative’s boundary-breaking work is on view to the public like never before. Organized by independent curator and writer, Antwaun Sargent, Virgil Abloh: “Figures of Speech” draws on the designer and artist’s decade spanning archive at an institution wholly personal to Abloh: The Brooklyn Museum. A native of the Chicago area, Abloh’s bond with New York was beyond doubt. After all, the bustling metropolis is where Abloh partnered with the likes of A$AP Rocky and Hood By Air founder Shayne Oliver—forecasting streetwear aesthetics into the fashion mainstream. “Virgil’s career took off in New York, he distilled his creative identity, his concerns, it all happened downtown,” Sargent tells V. “For him, doing a museum [exhibition] in New York was a very big deal.”

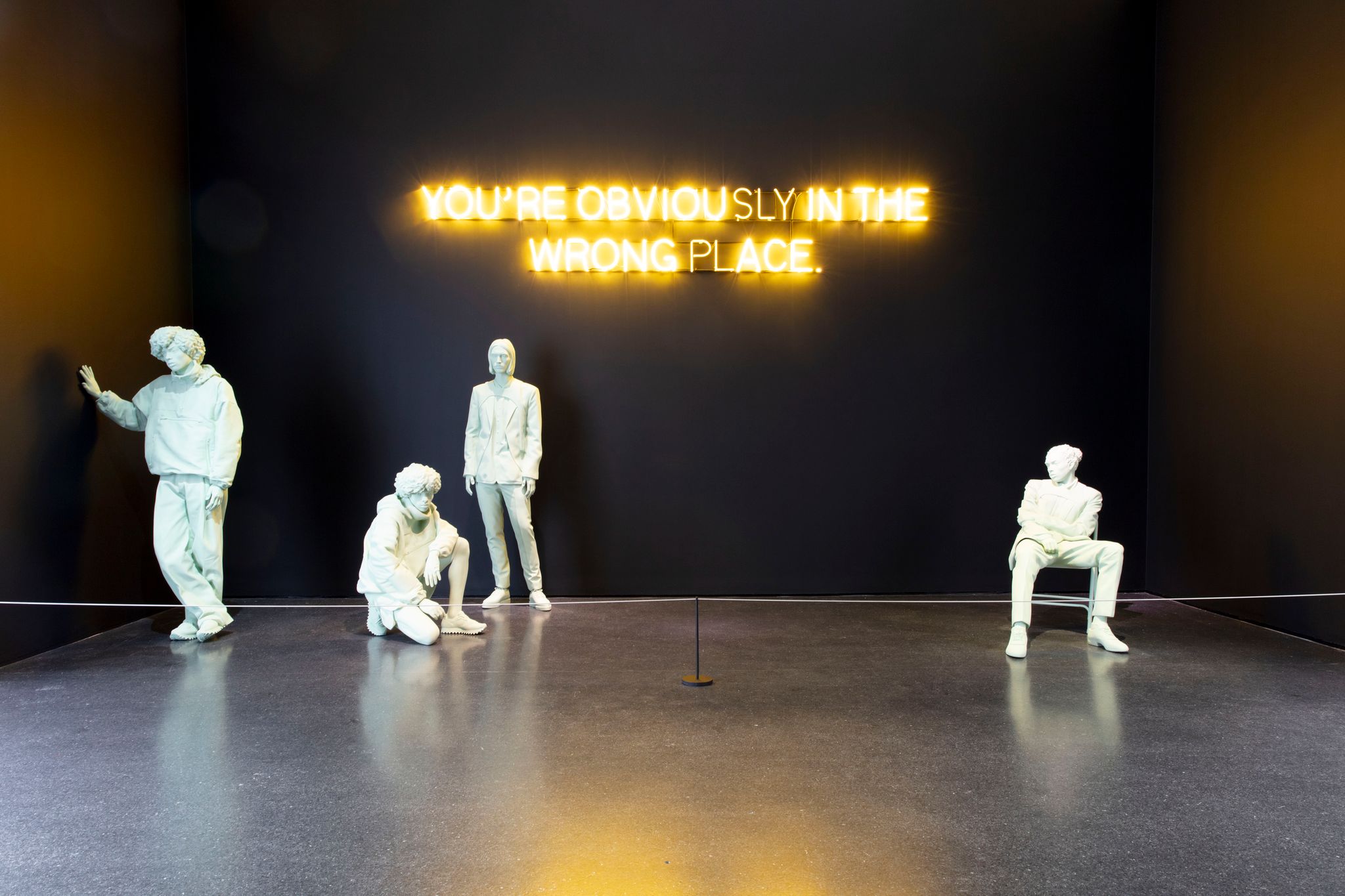

A bona fide multi-hyphenate in every sense of the term, silhouettes from Abloh’s tenures at Louis Vuitton menswear and Off-White are imagined alongside never-before-seen material, truly broadcasting the transdisciplinary nature of Abloh’s practice. Mannequins are substituted for structural tables and lively video displays, serving as an homage to both Abloh’s architectural background and dynamic, collaborative studio practice. “Virgil would say that he did everything for his 17-year-old self,” Sargent notes. “Why not bring those 17-year-old kids into the museum and have a creative exchange with people from various parts of Virgil’s creative sphere?”

And so too, the exhibition features an installation dubbed “social sculpture,” a rebuttal to the lack of space historically afforded to Black artists in cultural establishments. Just like Abloh’s monumental career, the space remains at the nexus of fashion, art, music, and collaboration, set on reshaping what fashion—and its many, ever-changing definitions—actually entails. “Virgil had this insatiable hunger to work in every medium and it could be confusing to people who put creatives in a box,” Director of the Brooklyn Museum Anne Pasternak explains. “There was no containing Virgil, he saw his practice as an artistic practice.”

Below, discover an extended Q&A with exhibition curator Antwaun Sargent and Director of the Brooklyn Museum Anne Pasternak!

V Magazine: First, can you take us through how this exhibition came about? What did the initial discussions with Virgil consist of?

Anne Pasternak: Virgil was developing the show for Chicago [and] his dream was always to have it in Brooklyn. He had come to visit on a number of occasions. He was slowly building a relationship with me [and] I didn’t know about the show in Chicago. And I was like, “what’s going on? Why is this cool guy trying to make a relationship with me?” But I realized this was because he was going to do the big survey show in Chicago and he wanted it to come to Brooklyn. He loved the idea that his work could be situated in the global, art historical context of an encyclopedic museum. And he was frankly really energized and inspired by the youthfulness and diversity of the Brooklyn Museum’s audiences. So from the beginning, he was really imagining the show here at the Brooklyn Museum, but he was also imagining it differently from Chicago. He wanted to go bigger for Brooklyn. He talked about this constantly—that he wanted to attract a young BIPOC audience to inspire them, to break down all barriers through their own creativity. And he wanted them to know that they did not have to be boxed in, that they could be a multitude of creative practices.

Antwaun Sargent: Virgil came to Anne and asked me if I would do the show in 2019 which was [when] it was supposed to happen. And then coronavirus shut things down and it gave us some more time to think about the exhibition. It gave Virgil and I basically two and a half years, I didn’t know it was gonna be that long. So it gave us two and a half years to think about what would be different and special about the Brooklyn Museum. I know that Virgil grew up outside of Chicago and lived in Chicago. But, where his career takes off is in New York, he distills his creative identity, his concerns, it all happens in downtown New York.

And so for him, doing a museum show in New York was a very big deal. And he wanted to think about the different ways that his career has grown since then, but also the different aspects—from design, to music, to architecture, to fashion, to sculpture. And he wanted to do that in the Brooklyn museum. And the show that we’re doing, is a completely different exhibition that thinks about his roots as an architect and making an intervention in the Brooklyn museum.

V: Can you discuss the curatorial process for the exhibition? How did the process begin and evolve?

AS: The process was through [a] deep dialogue with Virgil. What you’re going to get in this exhibition is not only some of the works that were in the traveling exhibition, but also things that he made. Over the past two years, we all were sitting at home bored, right? This is a man who never stopped traveling. For years and years, he was on planes—I think he logged 3 million miles in his life. And so what happens when you are stuck at home?

Virgil just kept making—he would do DJ sets, make sculptures, he would make books, he was a maker. And so we have some of those things in the exhibition that showed that despite the world stopping his creativity did not. And in December, he passed, and we wanted to make sure that the show, although it is not a retrospective, is acknowledging the fact that the show began as the expression of a living artist and it is opening as an expression of an artist who’s no longer with us. And so there’s parts of the exhibition that we changed to make sure that we acknowledge that as an institution, as a culture.

One of the things that I was very interested in, is that he was an architect. And as I’d gotten to know his team who are largely architects and graphic designers—the way that he thought and ran his various studios was like an architect. He sees that in every other aspect of his creative discipline—this pronounced sensibility of an architect, even in the fashion world.

And so the exhibition is going to be activated by his collaborators and students. Because Virgil would say that he did everything for his 17-year-old self. And so why not bring those 17-year-old kids into the museum and have a creative exchange?

AP: Virgil is really exceptional—he had this insatiable hunger to work in every medium and it could be confusing to people who want to put creatives in a box. But there was just no containing Virgil, he saw his practice as an artistic practice.

He considered himself an artist who worked in architecture, industrial design, music, fashion, but he was all about that plurality. That’s really our goal with this exhibition and it was his goal, in addition to inspiring young black and brown audiences. The goal is to have people see the fullness, brilliancy, and richness of his practice.

V: And one of the tenets of the exhibition is the ways in which it serves as a rebuttal to the lack of space historically afforded to Black creatives in institutional spaces. Can you expand on this point?

AS: One of the first conversations that Virgil and I had was about the lack of institutional support that he received—when someone’s super successful and they were the first creative director of menswear at Louis Vuitton, you have to think about all the people that failed to get there. This is 2018 when he gets that appointment, there have been Black designers before that. And he was very conscious of this, and it is one of things that we think about in the exhibition: acknowledging the fact that the museum itself, not necessarily the Brooklyn Museum, but the museum as an institution is constructed on exclusionary practices that had largely, until very recently, kept Black creators out of it.

And so when I say it’s an architectural intervention—what Virgil was interested in was creating something that functioned on its own logic. And so you might walk into the museum and one of his collaborators might be conducting a class with some high school students from Brooklyn on pattern making or how to make chairs or any other topic. DJs teaching folks how to mix, all of those things were important to him. And he did that in his own life to so many folks. Tyler the Creator, at his memorial service, gave a moving speech about how he called Virgil saying, “I don’t know how to make clothes [but] I really want to design a line.” And Virgil said, “Give me a week.” And in a week, Virgil calls him back with someone from a factory on the line, he had a pattern maker on the line. He had all these people ready to help Tyler. And you’re going to have that spirit in the exhibition.

V: What do you hope audiences gain from the exhibition about the work and legacy of Virgil?

AS: Virgil always wanted the freedom and space to express his creativity and ideas up to the very last moment—which is a challenge for museums. We’re really preserving the vision as he had it. If anything is different, it’s not so much how we approach the exhibition since his passing, but more so that people will be more receptive to the exhibition. Because it’s a survey exhibition, they will not be looking for one thing from Virgil. They’ll want experience all of Virgil, and that’s what they’re getting in this exhibition. All of Virgil.

AP: Definitely, if Virgil could do it, anyone can do it. And the exhibition, in some ways, deconstructs that logic. It’s not a retrospective in the slightest, it does not have that logic. But it does take a chronological view of Virgil’s creativity and creative output. It takes a view without hierarchy. And Virgil worked in a way, and lived as a person, where he treated everyone the same. Whether it was an industry figure or some kid on the street. And for me, the message is that when you walk through the exhibition and see this sheer creativity, how could you not be inspired to make something?

Discover More