#InMySkin Series III: Justin Wu Centers New Campaign On Indigenous Identities

Celebrating Indigenous bodies, 7 individuals reflect and embrace their culture and truth.

The beauty of storytelling is its longevity. We tell stories to uplift others, to entertain, or to enact change. A story is timeless, and holds endless possibilities of how we can reflect and interpret it. Most of all, a story allows us to open up about our shared experiences, and realize that even the most difficult challenges in life are never truly experienced alone.

This is the exact message director and photographer Justin Wu wanted readers to receive with #InMySkin. Since the start of the project in 2020, Wu has worked to combine his art with his passion for activism. In the wake of the #BlackLivesMatter protests, Wu focused his first #InMySkin Series on the Black community. And following #StopAsianHate in 2021, Series II was all about amplifying Asian voices. Both projects represented the purpose behind #InMySkin, and Wu’s desire to fight for social justice and equality.

“In a time when divisiveness seems to be ubiquitous, the continuation of this series is more important than ever,” said Wu. “By taking an active role in discovering, capturing, listening, and learning from different individuals and cultures do we enrich our understanding of humanity. I believe it’s not only the key to a more tolerant, sympathetic, and better society, but knowing how we can improve it for all.”

#InMySkin sheds light on social justice issues by giving minority groups a platform to voice their truth. Photographing these individuals in none other than their skin, the series symbolizes vulnerability and honesty, and more importantly, being confident and proud of who you are. It features different individual’s experiences, opinions, and upbringings, in order to highlight their communities and its issues.

To continue the conversation, 7 individuals of Indigenous backgrounds share their stories, personal upheavals, and ways we all can reflect and tell our own truths. View Series III of #InMySkin below.

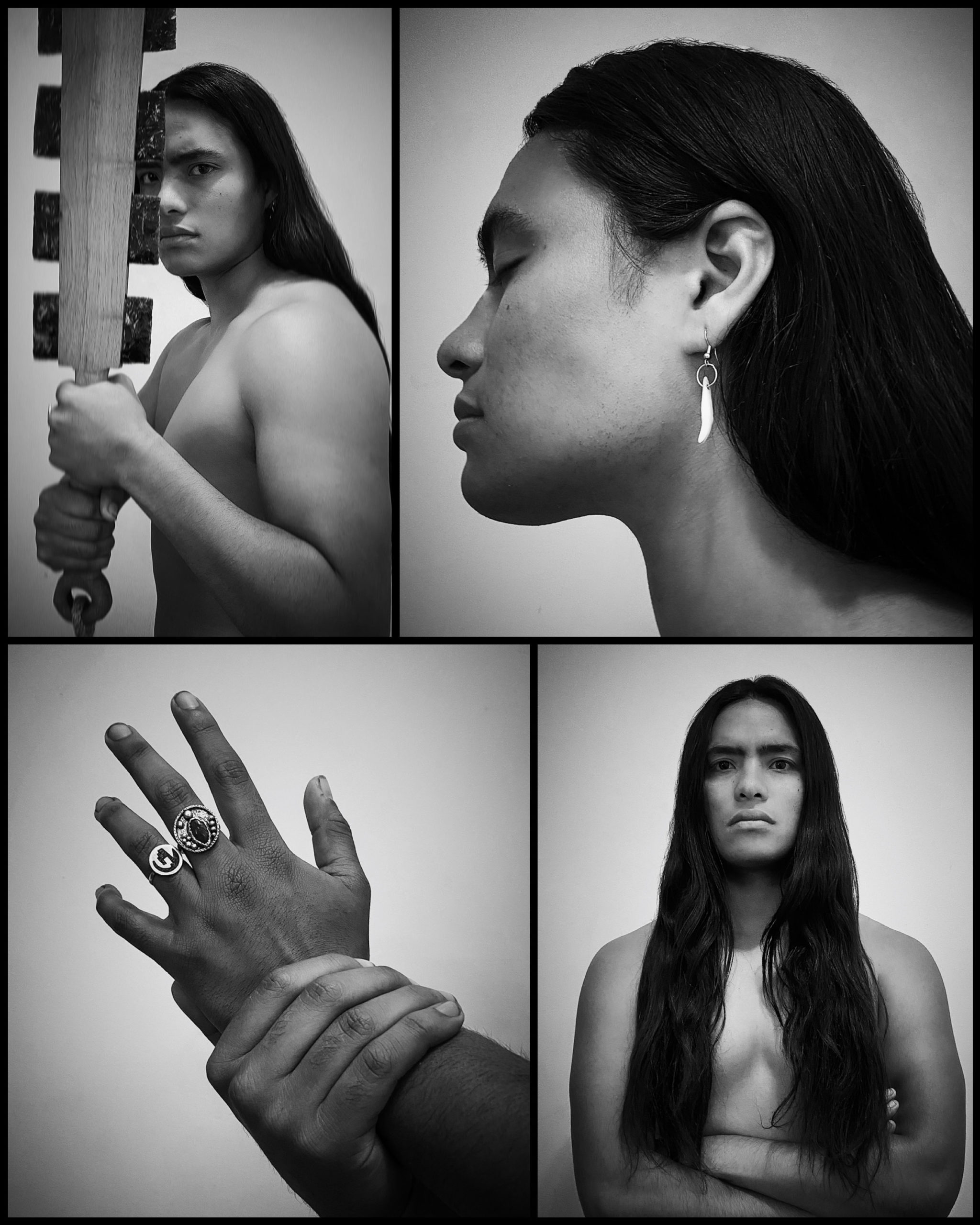

Haatepah – @haatepah

“I go by Haatepah or Coyotl. I am a detribalized Indigenous person since I was adopted as a baby. I donate to several Indigenous communities and organizations at the border. One that I like to support is @borderkindness.

I would like to reinforce and tell the world to be proud of your roots and where you come from..that we can’t run from our reflections as human beings Indigenous to this planet and to be proud of where you come from and give back.

We must Stand together because there is obviously strength in Unity. We must fight to help those without a voice and those whose struggles get washed away. These could be Indigenous people south of the border to what’s happening to Palestine, etc.

I wanted to feature my skin to show the world to be proud and represent it. The body echoes what the spirit feels.”

Julia Jones – @juliarjones

“American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.” – James Baldwin

“When asked to contemplate the experience of being in my skin, my first thoughts went to the concept of taking up space. How simple and basic that practice should be, and how arduous it has been. Not just for me, but for the generations of mixed race Indigenous women in my family before me. At times, existing feels like a radical act.

I don’t remember a time when strangers didn’t stare before routinely asking, “What are you?” Being in public meant feeling eyes scrutinizing, eager for answers. This led to a protectiveness that could veer towards isolation. But on the other side of that, there is a space I try to gravitate towards. It is a sense of being untouchable in a way. Of being unapologetically present and still. It’s simply being. And when that space is elusive, you just have to laugh. Through the pain, the frustration, the exhaustion, the absurdities. Sometimes you just have to laugh about everything.

Over the past year, I’ve thought a lot about how different everyone’s “experiences” are and about how much we decide to let other people’s experiences impinge on our own. We will always have unique realities, but what if we more closely considered the experiences of the people around us. If we took them on a bit more and held them closer to our own. Maybe, if we did that, we would all feel less isolated too. Less guilty, less superior, more compassionate, more fulfilled.

Some Indigenous-led organizations that are doing great work: Illuminative, Decolonizing Wealth Project, and The American Indian College Fund.”

Nat Kelley – @natkelley

“My name is Nathalie Rafaella Mallqui Kelley. Nathalie is the name my mother gave me at birth (a nod to her favorite actress Natalie Wood), Kelley is the name of the Australian step-father who raised me. And Mallqui is my maternal grandmother’s last name. It is a Quechua name meaning “deified mummy”. Mallqui’s were sacred mummies that were worshiped by the Incas. The Incas were my ancestors, and their Quechua language is still very much alive in Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia today. In fact, I am re-learning this beautiful language as a way of keeping our culture alive. My grandmother Rafaela (also my middle name) just turned 98 and still speaks the Quechua dialect of our ancestral homeland in the region of Huanuco, Peru. Huanuco is a fascinating part of Peru because it is where the famous mountain ranges of the Andes meet the Amazon rainforest. A place between two worlds. I think that sums up my existence too. My body, my lineage, my story — a place where two worlds meet. Colonized and Colonizer. High Tech and Lo-Tek. Ancient and Future.

I also want to acknowledge the Indigenous owners of Sydney, Australia, the land I grew up in. The Gadigal people, whose unceded territory is the place I was raised from the time I was 2 until 20. The Aboriginal people of Australia have been a constant source of inspiration for me. Their Dreamtime stories, their traditional, inherently regenerative ways of living with and off the land, their resilience in the face of blatant cultural erasure and genocide.

There was a time in my life when I thought that a western education was what Indigenous people needed to advance in society but now I see that it’s the other way around. We in the west, having run our resources into the ground and pushed this planet to the brink of ecological collapse, are the ones in need of a re-education. As Rutherford D. Rogers said, “we are drowning in information, but we are starved for knowledge”. And that’s what Indigenous people have to teach us. A wisdom rooted in the interconnectedness of all living beings. They carry the cellular memory of how to live in harmony with the natural world, how to be a beneficial presence on this earth, restoring and building biodiversity rather than destroying it.

That’s why I love educational groups like Children’s Ground, of Australia, who are reclaiming traditional, cultural and land-based education systems for Indigenous youth. And by doing so are ensuring that this precious wisdom is not lost.

Sadly due to colonization, we have already lost so much information that we desperately need right now, and a lot of it is connected to the loss of our languages. Our Indigenous languages carry thousands of years of culture and the accumulated wisdom of our ancestors. And that’s why I have started re-learning/remembering my own native language of Quechua with the group Viva El Quechua. Q’Orichaska my teacher is not just teaching me the language of my ancestors, but within that language a whole new cosmovision and way of connecting with all other living beings. For anyone interested in reconnecting with their indigenous heritage, language is a wonderful place to start. And for those who resonate with Quechua culture, I highly recommend checking Viva El Quechua out on Facebook for more educational videos on the language, music and culture.

Another great resource on Indigenous wisdom and technology is the book Lo-Tek by Julia Watson. It’s a fascinating read about how these technologies are inherently climate-resilient, nature-based, zero waste and or regenerative (giving back to the soil more than what we take). These are the technologies we need to apply today to reverse the damage that unchecked capitalism and the colonial mentality of extraction and exploitation have wreaked on this planet. A part of that shift is acknowledging our arrogance in considering these technologies to be primitive and useless, always giving preference to a western way of doing things.

Indigenous people represent only 5% of the world’s population yet they protect 80% of the world’s biodiversity. That is why we must join them in the fight to protect our last remaining pristine and wild places from extractive industries. And why should we care about the future of the Amazon rainforest for example, when we live thousands of miles away in big cities. Because these rainforests provide us with oxygen, they are major carbon sinks, remediating climate change. They are our last bastions of fungal and mycodiversity – from which potential future medicine and technologies can be harvested. Right now the Amazon rainforest has been deforested at a rate of 17 %. If we reach 25% it will turn from rainforest into a Savannah and it would be game over for life as we know it on the planet. We are all interconnected, we as humans are not separate from the ecosystem, we are very much an integrated part of it. The pandemic has shown us how sick we are, and that is because we are a reflection of how sick the earth is from our high consumption lifestyles and contamination. Indigenous people can teach us how to come back into balance with the ecosystem, finding our rightful place in the ecosystem. Where we can be a beneficial, not harmful presence on this earth. They are now discovering that parts of the Amazon rainforest were man made and designed, planted by (indigenous) humans. That means we still carry the cellular memory of how to be humans that build biodiversity and not destroy it.

That said, I want to acknowledge that in terms of lifestyle I very much fall into the category of someone in the west. I take and consume more of the earth’s resources than I give back. I aim to change that over the course of my life, but I want to honor certain indigenous groups who really walk the walk and have been resisting extractive industries for generations. One of them is the Kichwa community in Ecuador. They have a long history of fighting to protect their Amazon home and way of life. The Kichwa sisters Nina and Helena Gualinga are massive inspirations for me in that regard. Helena recently visited my home in California and I was honored to receive a necklace made by Kichwa women, a reminder of who the true heroes are in this story and symbols of true bravery and resistance. You can find out more by following @mujeresamazonicas , @ninagualinga, @helenagualinga.

There are some very sinister and powerful forces at work in today’s world that will do anything to protect their investments and interests. Make no doubt that these big multi-National companies are not just killing activists (Like Kichwa female activist María Tainz) but even bribing governments and judicial systems here in the United States. For example, between 1967 and 1992 Chevron (formerly Texaco) ignored regulations and dumped 16 billion gallons of toxic waste water in rivers and pits, polluting streams, groundwater and farmland in the Amazonian Ecuador. The court issued a 18 billion judgment against Chevron. Until now Chevron has not paid 1 cent in reparations, but have spent millions and decades instead framing and falsely persecuting the US lawyer Steven Donziger, who is now sitting in prison, serving 7 months after 2 years of house arrest. Both Judge Preska and prosecutor Rita Glavin both have deep ties to Chevron. For those that thought there was a free and fair judicial system in this country, you can now see the corrupt lengths these multinational industries will go to avoid compensating Indigenous people for damage intentionally done to their home and livelihoods, not to mention the unforgivable destruction to the once pristine portion of the Amazon rainforest.

Up until now the major news outlets refuse to cover Steven’s story. Ask yourself why. Thank you V Magazine for letting me share these truths here and for giving Indigenous people visibility and a voice.”

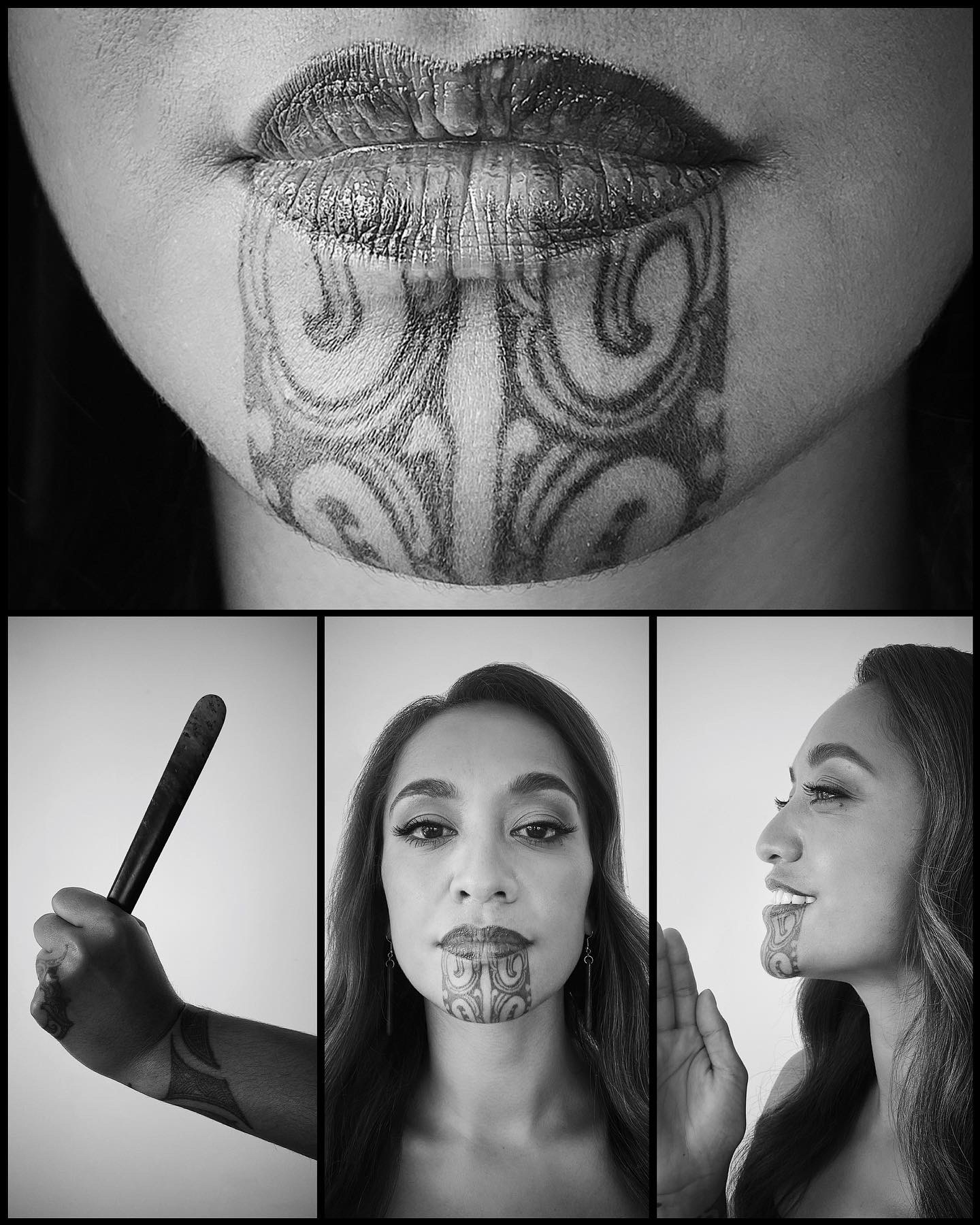

Oriini Kaipara – @oriinz

“E ngā mātāwaka tēnā koutou katoa – Greetings to you all.

In my culture, it is custom to introduce yourself by reciting your pepeha — a formal introduction that identifies where one is from, who they are, and where they belong based on their connection to their ancestral mountains, rivers, oceans, lands, and ultimately, to their ancestors.

Ko Putauaki me Pukenuioraho ōku Maunga

Ko Rangitaiki, Tarawera me Tauranga ōku Awa

Ko Mātaatua me Te Arawa ōku Waka

Ko Kokohīnau, ko Hahuru, ko Tātaiahape ōku Marae

Ko Te Pahipoto, ko Ngāi Tamarangi, ko Ngāti Raka ōku Hapū

Ko Ngāti Awa, ko Ngāti Tūwharetoa, ko Ngāi Tūhoe ōku Iwi

Putauaki and Pukenuioraho are my Mountains

Rangitaiki, Tarawera and Tauranga are my Rivers

Mātaatua and Te Arawa are my Canoes

Kokohīnau, Hahuru and Tātaiahape are my Marae

I belong to the Te Pahipoto, Ngāi Tamarangi and Ngāti Raka subtribes

My tribes are Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Ngāi Tūhoe

Ko Oriini Kaipara tōku ingoa — My name is Oriini Kaipara.

I am Māori, indigenous to Aotearoa New Zealand.

My pepeha doesn’t reflect my upbringing or the fact that I grew up far from my tribal boundaries.

I’m considered an urban Māori because I’ve spent much of my life in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland — the largest city in the country. The reason why my family moved here is because there was little to no work in our homelands. This is something shared by many Māori families, it’s known as the ‘urban drift’ where thousands of us were forced to find work and income in places far from our tribal lands.

In saying that, I’ve been called one of the ‘lucky ones’ because I was gifted my native tongue from birth, I also had access to my Māori world through my own family as well as a very special, unique system known as Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori. These are total immersion Māori structures that were pioneered in the 1980s, and were born out of a Māori language revolution.

Māori leaders from all over were fed up with the mistreatment and constant discrimination against Māori, for more than a hundred years. Our language was on the brink of extinction as a result of a law enacted in 1867 that prohibited te reo Māori on school grounds. The government of the time sought to assimilate Māori into Pākehā society and by any means necessary, often force.

Thousands of Māori children were beaten and punished physically, verbally, emotionally and spiritually for speaking their native tongue — the only language they knew. That caused a lot of fear, pain and shame. Entire families and communities stopped speaking te reo and as a result we lost our reo, our tikanga, and a very deep sense of connection to our heritage.

Now, I want to highlight Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa because this is a key part of my identity. It’s where I continue to draw much of my strength, courage, and confidence to do what I do today as a proud, indigenous, Māori woman.

My mother, my grandparents, and many of my whānau (family) set up a Kōhanga Reo in Central Auckland that benefitted not just us ‘babies’ but our families and communities. We had little to no resources because the government didn’t recognise Kōhanga Reo or Kura Kaupapa. We existed and relied heavily on our small, tight-knit communities, which at times did involve Pākehā. We raised funds ourselves, some parents mortgaged their homes to fund our schools and ensure our collective vision and dream would be realized. That dream — to ensure the Māori language and Māori way of life did not die. To ensure our taonga flourished and survived for many more generations.

To this day, thousands more graduates of these establishments have gone on to do great things here in our country and abroad with many taking on leadership roles in public and private sectors, others are breaking barriers and setting new records, while most are giving back to our communities by raising our tamariki (children) and mokopuna (grandchildren) the way we were raised – in their native tongue, at home and in our total immersion schools.

You see, we defied the odds then. Our parents and grandparents went against the grain and ‘did it’ anyway. They did what many criticized them for and about, with little to no support. They believed in the cause, they trusted in each other, and they committed their lives to our language and culture, and I am here because of them.

I am indebted to all my kaumātua, pākeke, and peers as well as our community of Hoani Waititi Marae in West Auckland. If it weren’t for them back then and now, I am certain I wouldn’t have come as far as I have in life, professionally and personally. The marae is the hub of the community, it is also the home of a Kōhanga Reo, a Kura Kaupapa, a Wharekura (high school), and many other Māori programmes for adult learners. It is a unique community that thousands of Māori call ‘kāinga rua’ or our ‘second home’.

I’m truly grateful and honoured to be able to call Hoani Waititi Marae my kāinga rua because, as an urban Māori, it provides a safe space for us to connect to our authentic selves and continue to learn and practice our customs every day.

Beyond this I want to acknowledge the hard work our reo champions across the country are doing and have done for decades. Specifically I want to acknowledge Sir Timoti Karetu who pioneered Māori language learning through ‘kura reo’ when he started the initiative at Waimārama in 1986. He is still teaching classes and remains the patron of kura reo in 2021. To all the kaiako (teachers), kaiārahi (leaders) in these language spaces I salute you and I thank you. You are all appreciated.

It’s important for us as indigenous people to hold fast to our traditions, our customary practices, and especially our mother tongue.

I know it’s not easy to reclaim any of these taonga when they were all taken from us and continue to be denied to many of us.

But the thing is our future generations miss out if we don’t take action now, and we know it takes just one generation to lose everything and a further three generations to reclaim it. So, we must make a stand today.

Who are we if we do not have our language? Can we confidently say we are indigenous if we no longer have our native language at the tip of our tongues and at the core of our existence?

A loss of language is a loss of culture. To lose your culture is to lose your identity.

When we speak our respective native languages we bring to life our ancestors, we reconnect with them and our past, and we enter realms that are only accessible through the beauty and spirit of our mother tongue.

I know it’s hard when no one else or just a select few people speak and understand your language, but it’s not about popularity or being accepted by the majority. It’s about retaining your very essence as an indigenous person. So, I want to encourage every indigenous person out there to start reclaiming what is rightfully yours, and to do so with an open mind and open heart. Know that your ancestors are always with you, especially when you feel like you’re all alone.”

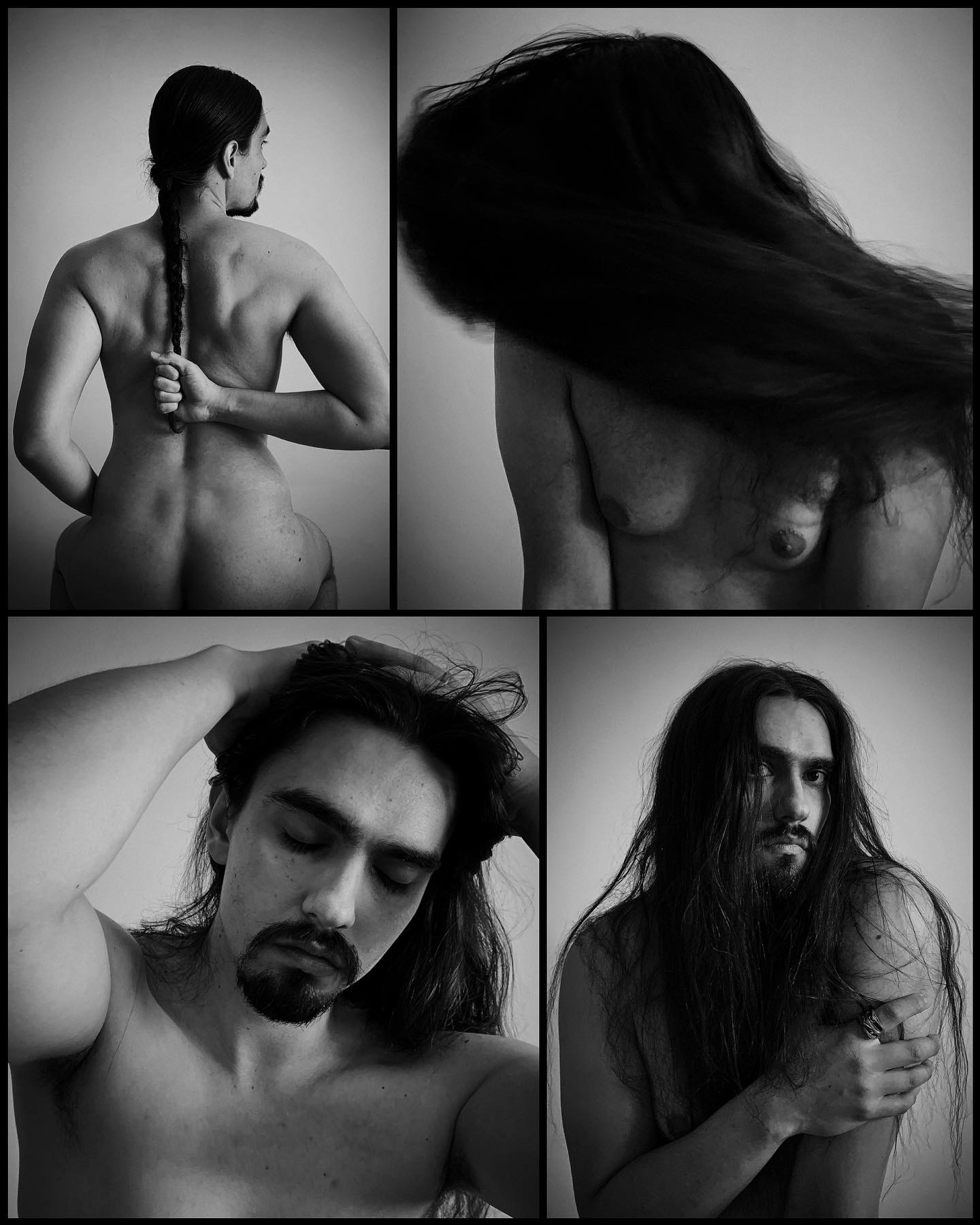

Riley Kucheran – @rskucheran

“My name is Riley, but I’ve been gifted the name Wiin-dash ga-biijaad Noopimiing-gii-biidood Oshki-mushkiki, which means “he who comes from the old forest with new medicine.” It takes a lifetime to come into one’s name, to learn its lessons and embody its teachings. As an Indigenous educator and researcher, I interpret this name as a responsibility to remember: to go back in that old forest and gather the ancestral ways of being which present generations need to ensure our future. Indigenous fashion is an incredible artform that provides us with tools and resources to do this, in an important moment of cultural resurgence.

Our fashions nurture better relationships to Land and all its relations through sustainable practices. Indigenous modes of making are inherently communal: the process involves deep reciprocity and requires many different kinds of knowledge holders. A ‘supply chain’ in Indigenous fashion starts with Elders: storytellers who guide hunters, hide-tanners, medicine cultivators, weavers, and the designers who coordinate this beautiful collaboration. In my work I’ve positioned this fashion as luxurious, as deserving more recognition than the finest European couture, for its material and aesthetic qualities but also its spiritual connectedness.

Apart from attending a few Pow Wows as a youth, I wasn’t raised within Nishnaabeg culture. My parents met in Thunder Bay: my father’s Ukrainian family had settled in Saskatchewan and my mother’s Ojibway family came from Biigtigong Nishnaabeg (Pic River 50 First Nation) and other places on the northern shore of gchi-gami, or Lake Superior. But like so many Indigenous peoples, we were dispossessed from that territory. Devastating legacies of genocide, like the horrendous “Residential Schools” that systematically removed and abused Indigenous children in order to assimilate them, had direct impacts on my family. We were taught to be ashamed of our culture. I didn’t learn my language or participate in ceremonies. We lived off-reserve, in violently racist places before I fled to Toronto to pursue fashion. Reconnecting to Nishnaabeg culture in my twenties has been a wonderful and challenging journey. I’m grateful that it brought me to Indigenous fashion, and that it also brought me ‘home.’

I’ve spent the last two years in Biigtigong, teaching virtually during the pandemic and learning and healing on the Land. Biigtigong means the place where the river erodes, and it’s the geographic and spiritual heart of our territory. Flagged by beautiful coasts of rocky hills and white sand coves, Biigtigong is the historic summertime gathering spot for a vast network of Nishnaabeg who lived and worked along the rivers in the dense boreal forest. This Land is infinitely generous and sustaining, and despite waves of extractive industries that continue to abuse our territory and sovereign rights, we remain strong, forward thinking, and ambitious in our pursuit of getting Land back and living in authentic, ancestral ways.

Soon I’ll return to the city and the Creative School campus at X University (formerly Ryerson), where my colleagues in Fashion have been transforming the curriculum to center inclusive, sustainable, and decolonizing perspectives. I’ve been weaving Indigenous theory, histories, and design methods into a number of courses, including in business where we explore principles used by EntrepreNorth, an Indigenous-led incubator; and land-based studios developed after my time at the Dechinta Center for Research and Learning, an Indigenous-led school. I also sit on the board of Indigenous Fashion Arts led by Sage Paul, who’s been preparing for another Indigenous Fashion Week Toronto in June of 2022. All of these organizations are directly impacting Indigenous communities, and at the root of their work are strong Indigenous values.

Fashion is inherently colonial. Its structures and systems were founded with racist ideologies that continue to exploit people and the planet. It’s been called capitalism’s ‘favorite child’ because fashion perfected commodification. It’s antithetical to Indigenous design, so participating in this system can be dangerous. To Indigenous creatives I say stay steadfast. Cultivate your cultural roots. Take care of yourself and your relations. Get political. Protest. Protect ancestral knowledge. The most recent embrace of Indigenous culture by mainstream fashion media is welcome, but there’s cause for concern. I hope this is more than a trend. That said, I am deeply grateful to Justin Wu, Yael Quint and V Magazine for this Series and platform.

To me “skin” is synonymous with “body.” It’s a vessel for our holistic selves, our histories are held in its scars. I recall Cree poet Billy-Ray Belcourt’s (2017) essay, The Body Remembers When The World Broke Open, also the name of a (2019) film by Elle-Maija Tailfeathers and Kathleen Hepburn. Bodies like mine, miraculous bodies not Missing and Murdered, hold generations of pain and trauma. Indigenous peoples have been living through our apocalypse for over 500 years. The survivors are haunted by a past that suffocates our present while we dream the future. I tend to my scars because my healing is for the next 7 generations.

I chose to feature my hair and my whole body. The braids of boys were cut off in Residential School, making long hair an act of resistance. It’s a constant reminder of my recovery. It was also liberating to pose nude because I’ve hated my body for most of my life. It’s been targeted and taunted, used and abused by others and myself. Coming into body has been my most difficult struggle. I identify as Two-Spirit, but Indigenous languages have many ways to describe gender embodiments and roles. In As We Have Always Done (2017) Nishnaabeg scholar (and my doctoral supervisor) Leanne Betasamosake Simpson recalls a kind of ‘Queer Normativity’ in which trans bodies, diverse sexualities and polyamorous relations exist within normal community dynamics. I’ve found strength in this, and I’ve started to unpack hatred as part of colonialism itself. Today my body provides hope when the world feels hopeless.”

Sage Paul – @sagepaul

“My name is Sage Paul. I was born and raised in Toronto with regular visits to my family territory in Northern Saskatchewan. I am a member of English River First Nation in treaty 10. We are Denesuline, which means people of the poplar trees.

There are a number of Indigenous-led organizations that I would recommend people look into and support: Indigenous Fashion Arts, Native Women in the Arts, and the Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction.

It’s important that we care for each other and the land we live on, to protect each other’s families and the future generations to come.

Justin and I spoke about what is important to me. I said family and community. I wanted to share photos that were bare, in that I am open with my family and community. Though, I also wanted to show transparency and openness in two-way dialogue, that I also receive love and comfort from my community. The red hoodie, which is a gift from a friend, is significant for its colour which often represents Indigenous people and our unity that is wrapping me in safety.”

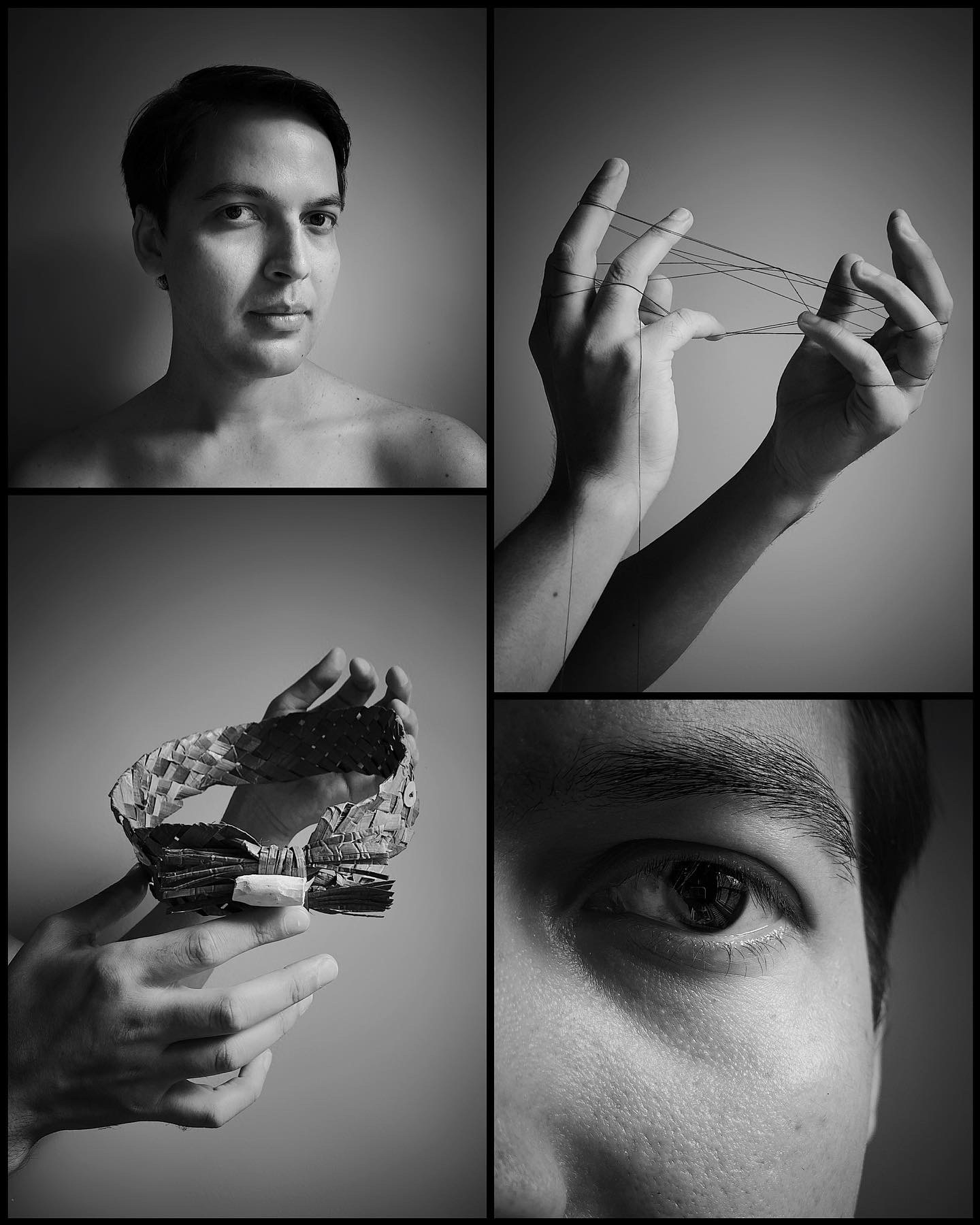

Warren Steven Scott – @warrenstevenscott

“I am a member of Nlaka’pamux Nation, I’m Interior Salish and Lower Salish, whose territory is located in the interior of present-day British Columbia. I live and work in Toronto. We have a large family, from Boothroyd First Nation, they’ve supported my whole life. They sponsored fashion education, provided funds for me to buy an industrial sewing machine. All the clothing I make is made with that machine. I wouldn’t be able to create what I do today, without their support from afar. I’m thinking of a story my uncle Ric recently told me, something his father, my Grandpa, always said to him, “you are Nlaka’pamux wherever you are”. My family really makes me feel that way.

“I am a member of Nlaka’pamux Nation, I’m Interior Salish and Lower Salish, whose territory is located in the interior of present-day British Columbia. I live and work in Toronto. We have a large family, from Boothroyd First Nation, they’ve supported my whole life. They sponsored fashion education, provided funds for me to buy an industrial sewing machine. All the clothing I make is made with that machine. I wouldn’t be able to create what I do today, without their support from afar. I’m thinking of a story my uncle Ric recently told me, something his father, my Grandpa, always said to him, “you are Nlaka’pamux wherever you are”. My family really makes me feel that way.

I’m continuously inspired by the work of Toronto Indigenous Harm Reduction.

Do you know why we are resilient?

So much has been lost, languages, land, craft, people — and we continue to find resilience, to support each other. We must continue to be resilient, to connect, and support each other — that is the work, so we do not lose more. I said before, the quote from my grandfather, “you are Nlaka’pamux wherever you are”, this is also the work, to be a person, to create — when you and your work were not supposed to be here. The very act of me creating art or work today, challenges the Indigenous erasure that continues across this country. I will continue to create.

I chose to feature, not too much of my body/skin — I think this is in part due to what I was comfortable showing, but also because of what I create in my work. I make clothing, I cut, I sew, I love what clothing can translate, how it can make us feel. That is why we show my hands, my fingers, with thread — the stories they are able to tell, through the work they create.

My eyes connect literally to what I see, but also to who I am, a contemporary Indigenous artist. They are my lens to translate how I move in the world, a person connecting and creating today, but connected to an ancestral worldview.”

Discover More